We reconstruct or “restore” prairies to learn about the ecosystems that built our soils, to control erosion, and to support native insects and pollinators. But how are prairies reconstructed?

First, a note on semantics:

We often refer to the process of planting native prairie species on land that has been used previously for crops or grazing as prairie restoration. Instead, I will refer to this process as prairie reconstruction. This is in order to emphasize the magnitude of what we lost when we lost our native prairies. We cannot restore, or bring them back exactly as they were because they were created over hundreds of thousands of years by glaciations, deposition of nutrients, and thousands of years of growth and interactions among prairie species. There is no way for us to reproduce the quality of native prairie remnants in our reconstructions within a short timescale. Additionally, we don’t usually have records of which species were present on the land before European colonization, since settlers usually viewed the prairie as emptiness waiting to be planted with crops rather than as a noteworthy ecosystem. This means that we lack a historical “baseline” to which we could restore prairies.

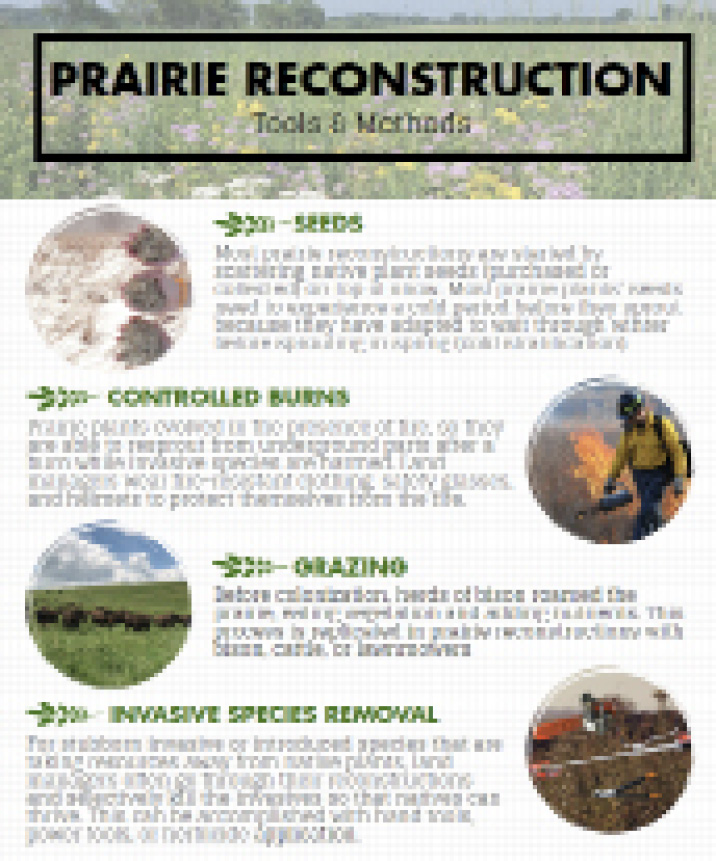

The infographic on the following page was made by combining and modifying images from me, from Jon Andelson, and from Wikimedia Commons users including cassi saari, Bene16, Appaloosa, Dvortygirl, USFWSmidwest, and various uncredited images uploaded by U.S. government employees.

How can you get involved in prairie reconstruction?

- Call your local county conservation board, DNR office, or wildlife preservation areas. Many hold volunteer days to collect seeds or remove invasive species as part of community outreach efforts.

- Plant native prairie species in your yard at home! Though its benefits are not on the same scale as prairie reconstructions, planting native species still helps out pollinators and established natives require no water or fertilizer. For more information on planting native prairie species, visit ISU Extension.