One bright spring morning nearly twenty-five years ago I was sitting with some colleagues around a seminar table in a Grinnell College classroom sharing opinions about a wide variety of topics. The occasion was a breakout session at an all-faculty retreat. We were talking about the curriculum, the demands of teaching, work-life balance, students, and the general state of the college.

“Grinnell is a good place to teach,” one of my colleagues said at one point. “Too bad it’s where it is.” As I recall, she went on to lament that the college wasn’t in St. Paul, Minnesota, but I think that was just a for-instance. Someone else agreed and said, “how about Santa Fe?” “Or Santa Barbara,” another chimed in. What was it about saints, I wondered? (Our local coffee shop is named Saints Rest, but clearly that wasn’t sufficient.) I remember feeling sad about the direction the conversation was taking, and a bit irritated, but I said nothing.

During the coffee break that followed the session I found myself sitting outside with my friend Jackie Brown, a member of the Biology Department, who had been in a different breakout session. I decided to share with Jackie what I’d just heard and how it had made me feel. Somewhat to my surprise he said, “I heard the same thing in my group, and it pissed me off, too.”

“It’s not as if the College is going to move,” I said.

“They should settle in and get to know the place,” Jackie said.

In fact, at that time the college as an institution was doing a pretty good job of ignoring its location, and even apologizing for it. One Admission brochure said something to the effect that “Grinnell might be in the middle of corn fields, but it’s a great school.” A subtle—or maybe not so subtle–slap in the face . . . to the town, the state, and corn. As Jackie and I talked, ideas for pushing back against this attitude began popping into our minds. In the weeks that followed we brought together a number of other colleagues from across the college who we thought or hoped shared our views, or at least could be brought around to them. To make a long story short, the result was the decision to create a Center for Prairie Studies at Grinnell.

The Center’s mission, as we conceived it, was to celebrate and use our location as a teaching and learning resource instead of ignoring it, letting our location, as one of our colleagues put it, “be our text, our stage, our canvas, our laboratory, and our archive.” But how did we think of our location, and what should we call our Center? We considered Iowa Studies, Midwest Studies, Rural Studies, and some others that I cannot now recall, but in the end we decided to designate our location as “the prairie region of North America.” In this we were influenced by a statement in a history of Iowa, prepared for the Bicentennial of the United States by Grinnell College historian Joseph Frazier Wall. “The history of every state must … begin with the land itself,” Joe said. “For Iowa, the land serves as more than an introduction. It is the main story line.” 1 In 1850, roughly 80 percent of Iowa was tallgrass prairie, the highest proportion of any state. Even though a century later 99 percent of the original prairie had been destroyed to make way for Euro-American agriculture, the prairie’s influence on Iowa’s development endures to this day.

Image Courtesy of Grinnell College’s Center for Prairie Studies

I have told this story many times, but until now never committed it to print. Although the story is the same, publishing it here changes it. Putting the story in print makes it part of a more durable record. That is one goal of Rootstalk: A Prairie Journal of Culture, Science, and the Arts: to gather stories from the prairie region and to share them with our audience. Most of the stories are told in words, but some are told in images or in sound, and some in all three. The stories are literally everywhere; we just coax them into the open and put them in a storehouse or, if you will, a storyhouse.

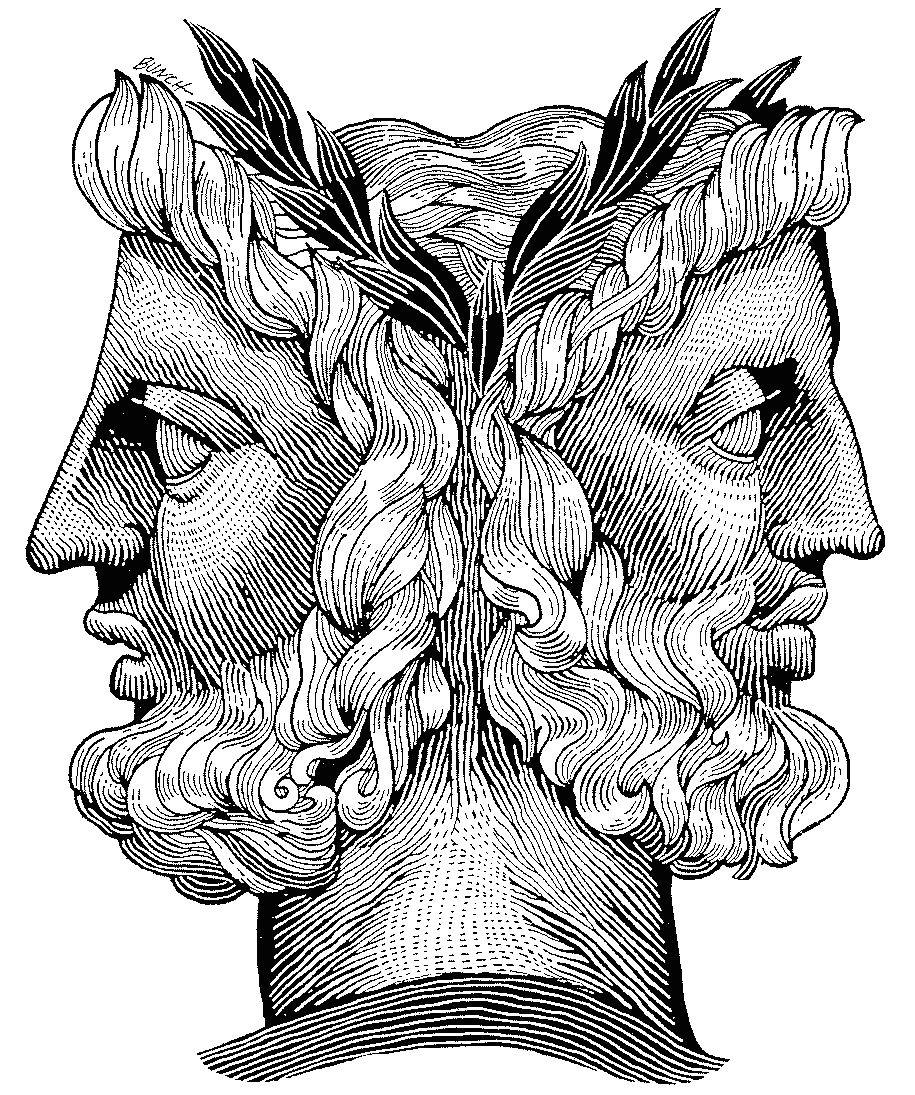

I have been thinking about stories a lot lately. This seemingly straightforward category contains its share of enigmas. For example, I cannot decide if we once were the stories we tell, or if we become the stories we tell, or if the stories, like Janus—the Roman god of doors, gates, and transitions—face backwards and forwards simultaneously, connecting the past to the future. Are stories wisdom or wish or warning? The word’s derivation is a story in itself. “Story comes via Anglo-Norman estorie from Latin historia (‘account of events, narrative, history’).” 2 We can trace the word farther back to the Greek histor, originally widtor, meaning “wise” or “knowing,” thence back to an Indo-European root, weid, “to see or look.” 3 Thus, seeing allows us to know things, and we give accounts of what we saw, and of what we know from seeing, in the stories we tell.

I notice stories everywhere, but this was not always the case. I used to think of stories as fictional narratives. I did not think of myself as collecting stories when, as an anthropologist, I would conduct interviews with people about their cultural practices and norms; I was collecting evidence—facts, not fictions. Nor did I think of the news on television or in newspapers as stories; again, these accounts were factual. (Editorials might be opinion rather than fact, but that still was different from fiction.) Scientific reports, also, were not “mere stories” but based on careful methods for systematically gathering information, data. In my mind, the phrase “it’s a true story” only highlighted the idea that most stories were not.

My perspective on stories began to shift under the influence of a current Grinnell student. I first met Emma Schaefer in the Spring of 2020 when she enrolled in the Digital Journal Publishing class that I co-teach every spring with Mark Baechtel, Rootstalk’s Editor-in-Chief. Emma took the class, she told us, because she thought it might contribute to the independent major in Multimedia Storytelling she was pursuing. That sounded interesting, but, I thought, limited. However, the more I listened to Emma, and the more I began to pay attention to what other people were saying about stories, and the more I thought about the broad etymology of the word “story,” the less I felt that stories lay on one side of the line I had drawn between fact and fiction. Put another way, stories transcend that distinction, which in any case is not the most important thing about stories. Rather, the most important thing about stories is that they convey a message about how things were, or are, or might become. They are tools for describing and illuminating the past, the present, and the future.

Consider what the author Beth Hoffman says in her new book, Bet the Farm: The Dollars and Sense of Growing Food in America, an account of the challenges she and her husband faced moving back to Iowa to take over his family’s farm and move it in a more sustainable direction: “Yet as I outlined in the previous chapters, there is much that we can do as individuals, as farms, as groups of farms, and as a nation to improve the system [of agriculture], all of which start with changing the stories we tell about farming.” 4

Janus, Roman god of doorways, gates and transitions. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Or consider what Keith Kozloff, formerly a senior environmental economist at the U.S. Treasury Department, said to me recently: “After spending much of my career working on climate policy, but seeing insufficient action, I came to the conclusion that one of the legs missing is the political and public will to make change. How do you mobilize that? It’s got to be done by engaging people at the heart level. Story-telling has emerged as central in that.”

Or consider what Kamyar Enshayan, the Director of the Center for Energy and Environmental Education at the University of Northern Iowa, said at a talk he gave in Grinnell recently. His subject was how the world, and especially the United States, could meet our energy needs without pumping yet more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. “The future of energy is almost always framed in terms of supplies, ‘where can we get more of this or that?”It is rarely framed in terms of demand reduction,” Kamyar said. “Furthermore, solutions aren’t always technological. What kinds of cultural transformations do we need to make? What kind of stories can inspire us to reduce demand?” 5 He proceeded to talk about things from the past like ice houses, electric public transporation, hanging clothes on lines to dry, and home gardening that used much less energy than their modern counterparts.

John Everett Millais, “The Boyhood of Raleigh” (1870), from the collection of the Tate Gallery, London. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

What Beth, Keith, and Kamyar are implying is that all of us live our lives—believing certain things and behaving in certain ways—based on stories we have heard. In the absence of a story, we might lack the will to act, as Keith suggests. If we have been taught untrue stories, our own actions or our tacit acceptance of the actions of others can be misguided, as Beth argues. If we have forgotten certain stories from the past, the options for action in the present are curtailed, as Kamyar believes. Ultimately, we need to tell stories, true stories, to inspire right action. Of course, fictional stories can also serve these ends; we can find great inspiration in the writings of our novelists, poets, and playwrights, whose stories are true though fictional. What we must be on our guard against are stories that are lies, or that cause environmental degradation, or that demean or incite hatred.

In this issue of Rootstalk, and every issue, we offer stories about the prairie region in hopes of shedding light on the region’s past, present, and future, and in hopes of inspiring thought and action that will contribute to the health and well-being of its natural and cultural features.

Postscript: This issue of Rootstalk contains photography by Keith Kozloff on the cover and a song by Emma Kieran Schaefer.

1 Joseph Frazier Wall, Iowa: A Bicentennial History (The States and the Nation Series, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978, p.xvi)

2 John Ayto, Dictionary of Word Origins (New York, Little, Brown and Company, 1990, p.504)

3 Calvert Watkins (ed.), The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, 3e (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011, p.99)

4 Beth Hoffman, Bet the Farm: The Dollars and Sense of Growing Food in America (Island Press, 2020).

5 Kamyar Enshayan, personal communication, March 15, 2022

The editorial staff for the Spring 2022 issue of Rootstalk. First row, from left to right: Editor-in-chief Mark Baechtel, Associate Editors Liz Neace, Taylor Kingery, Kendra Bradley, Harrison Kessel, Publisher Jon Andelson. Back row, from left to right: Carlie Duus, Xonzy Gaddis, Hannah Agpoon, Mikayla Trissell, Ian MacMoran. Absent from the photo are Associate Editors Robby Burchit, Avery Hootstein, Zainab Thompson, and Fernando Villatoro-Rodriguez. Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson