As befits an article prepared by the members of a collective, no one person gets by-line credit for this piece. It was put together through the strenuous efforts of “a collective group of farmers and gardeners” working with Mustard Seed Community Farm, an agricultural operation which follows the CSA (community supported agriculture) model north of Ames, Iowa. According to Mustard Seed’s mission statement, its workers are “inspired by the examples of The Catholic Worker, Gandhi, and many others. The community seeks to create an environment in which everyone can participate in growing, distributing, and eating good quality food. We are committed to service: To our workers, to the land, and to the hungry.”

Balance? What Balance?

by Alice McGary

When I got the message from Rootstalk’s publisher, Jon Andelson, asking if we wanted to write an article about Mustard Seed Community Farm, my first response was, “Oh no!” This wasn’t a simple, calm “No.” That’s because I knew that writing for the journal would be a good thing to do. I love our farm, which is 100 percent volunteer-run and dedicated to sustainable, simple living, love of our neighbors, and creating a community in which everyone can participate. I love that we grow healthy, chemical-free food to share with the community. I love the things we believe in and have been trying to bring together since we began in 2008–justice, agro-ecology, human scale economics, community, beauty. And I love the things that Rootstalk believes in–culture, science, art, prairie, place. It’s a great fit to have something about the farm in this journal. But trying to consider all this simultaneously makes me dread trying to create anything coherent and honest out of my confusion.

So much has been going well at our farm. We have accomplished so many goals and have such an amazing community, but really, my partner Nate Kemperman and I are more confused and exhausted than ever. Nate and I have been trying to farm in this wildly idealistic, collective, gift-economy way for fifteen years now with a slowly shifting team of founders and co-creators. Farming and living the way we do is not common in Iowa these days, and–in many ways–the Mustard Seed values are not those of the dominant culture surrounding us. You can see that difference just by looking at our small farm, vineyard, and prairie and the fields of commodity crops surrounding us.

As industrialism and colonialism have transformed our world, many everyday skills held by everyday people have been lost. These are simple but fundamental things, such as identifying plants and weeds, as well as methods of foraging for food, caring for animals and the soil, planting and saving seeds, pruning perennials, making compost, shearing sheep, processing wool, sewing, preserving food, or cooking with seasonal ingredients. As we lose these skills, we lose touch with our natural world and our cultures, and our communities lose the ability to be resilient in crises such as our current pandemic. Our rural communities are losing people and skills, and we are losing the ability to be good neighbors because we don’t have the diversity of agricultural skills to help each other in times of need.

We face multiple challenges in fulfilling our mission. Farming is hard work. Climate change is crazy. Beauty and connection are what give us strength and joy; justice and truth give us purpose. But do people even want justice? Are we making any kind of difference? How do we build community, grow food, make music, weave, craft pottery, raise sheep, and share meals without running on empty? How do we make time for personal needs when there’s so much work to do and we care about that work so much? Two years of pandemic and increasing drought have left us with more questions than answers. And in trying to answer these questions, we have also struggled to balance all our loves.

I’ve been trying to figure out how to balance being an artist, a farmer, and a person. I farm and make art to bring people together and to try to make the world a truer, better place. Sometimes that means feeling, thinking, and talking about hard things. Sometimes that means taking the time to really savor and celebrate the mystery, beauty, intricacy, and majesty of this world we share. Sometimes that means putting in the hard work to get things done. Today, it didn’t mean trying to solo-write a creative article. Luckily, we don’t have to do this work on our own: one of the blessings of being part of a community is that there are others on our team to share the load when things get tough. So, I asked some folks from our Mustard Seed team to help co-create this story. In what follows, you’ll hear from Amie Adams, Zoë Fay-Stindt, Benjamin DuBow, and Emma Kieran Schaefer. Each brings a unique perspective to our story.

Winter Sowing

by Amie Adams

We first met to discuss this article by video call in March. We shared ideas, trying to envision how to weave a story from our voices. Three of us who hadn’t visited the farm much over the winter felt especially challenged to find words about life and growth while surrounded by a bare, still-frozen landscape. But just a few days later, an unseasonably warm and bright-hazy afternoon found us out on the farm–coatless–greeted by pungent, muddy earth and rumbles of affection from the cats. Sitting on the warm pavers near the wash station with Shadowbeast on my lap, I listened to my friends share their ideas. We talked about the importance of beauty and of rest, and of how we need them just as much as food. “Bread and roses,” Alice said. “It’s from an old labor song.” She tried to match a tune to the line “hearts starve as well as bodies, give us bread, but give us roses.”

“Exactly,” said Jen McClung, who had come to win-ter-sow poppy seeds. “Beauty is essential. But it’s more– it’s an invitation. When we plant flowers, we invite pollinators to share this space with us. To them, flowers are more than beauty and attraction. They are food, safety, welcome.”

We paused to absorb her words. “Yes,” Zoë said, and the rest of us nodded in agreement. “And that’s what we offer to people…”

“And all the beings we share this space with.”

At the mention of insects and people, our conversation turned to the Shabbat dinner Benjamin had hosted the September before, and the masses of picnic bugs who had joined for the occasion. We laughed in good-natured disgust and told Jen about how we picked them off of one another’s clothes, and out of our hair, saved them from our wine glasses, and most definitely overlooked and ingested some that hid among the seeds on the challah.

“It’s gross, right?” Benjamin said. “But I think there’s something to it.”

“It’s all connected, isn’t it?”

We looked at each other and nodded in agreement.

“Okay,” Alice said. “It sounds like we have something.”

Wait. You’re Farming?

by Amie Adams

Mustard Seed is the first place in Iowa where I planted vegetables. On one of my first days as an intern, I found myself alone with Alice, hoeing a furrow for kohlrabi seeds on an overcast April afternoon. As she demonstrated how to sprinkle tiny maroon seeds over the soil and press them gently into the row she turned to me and asked, “Do you feel how dry the soil is? We haven’t had enough rain.” I nodded and she went on, “It’s stressful–sometimes I wonder if I’m crazy, trying to be a farmer during climate change.”

My family history in Iowa dates back to the mid1800s when my ancestors immigrated from Northern Ireland and Germany to Kossuth and Chickasaw counties and started farms. The last farmer in my family was my grandpa on my father’s side, who gave up farming in his 20s and moved “to town” (Ionia, current population 269) to run an automobile service station. The family farm where his grandparents homesteaded in the early years of Iowa’s statehood now belongs to an Amish family. Lately, I’ve found myself dreaming about visiting and filling one of my grandmother’s old blue Ball jars with handfuls of that soil.

What does it mean to belong to a place? Especially when an entire different culture belonged there first? What does it mean to belong to a state radically altered by generations of farmers, including my ancestors?

These questions, a sense of responsibility to Iowa–to soils, plants, animals, waterways, and people–and the persistent feeling that I wanted to belong to this place in a radical way, led me to Mustard Seed. I moved from northern to central Iowa by way of a four-year detour in Colorado, and I found at Mustard Seed a kind of alternative agriculture I had seen in the West but never experienced in my home state. It was as if all these possibilities were hiding in plain sight, on eleven sloping acres beside the Ioway Creek, where I interned for a season, helped plant and care for more varieties of herbs and vegetables than I ever knew existed, and fell in love with Iowa’s wild and native plants as if for the first time–all while guiding my sore, dirty, sweaty body through an intense drought alongside Alice, Nate, and the other interns and volunteers.

I felt a special thrill as the seedlings I planted began to emerge from the soil, and I kept a mental list: kohlrabi, radishes, kale, cabbages, onions, lettuce, spinach. As the growing season stretched toward summer, I found myself basing entire conversations with my family members around a list of everything we were coaxing from the earth.

“Wait, you’re farming?” family members asked.

“Yes, but not like you’re thinking,” I’d reply. “No corn. It’s a small farm. We grow a bunch of fruits and vegetables. Let’s see, there’s asparagus, rhubarb, cabbage, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, radishes, onions, garlic, beets, spinach, lettuce, chard, peas, green beans, celeriac, melons, squashes, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, okra, potatoes, raspberries, strawberries, gooseberries, currants, honeyberries, blueberries, Aronia berries, cherries, apples, peaches, plums, grapes, basil, sage, fennel, lemon sorrel, parsley, cilantro, oregano, sunflowers, zinnias, poppies…” I’d go on for as long as I could.

No matter who I bombarded with this list, they were astonished, just as I continue to be. In 2021, these acres tucked within miles of commodity crops taught me the abundance of life in the prairie and savanna, edible and medicinal wild plants, chickens, sheep, and bees. To an Iowan whose whole framework for agriculture once hinged on industrial corn, soy, and hogs, Mustard Seed has been a revelation. It is a place, a community, a way of being in the world, that I’d only imagined before. When I think about my first season on the farm, it’s that early conversation over the kohlrabi seeds that strikes me. I recall Alice and me–she fifteen years into her life at Mustard Seed and wondering what the future holds–me, inexperienced and full of over-eager optimism. As Alice’s fingers expertly plucked the delicate seeds from her open palm and dropped them along the row, she said “I guess I want to face reality…so I farm.”

At A Long Series of Tables

by Zoë Fay-Stindt

We gather on the farm for Shabbat, listen

to Benjamin sing out across the corn fields

surrounding this small oasis, picnic bugs

swarming the sch’ug, tahina, hummus

curved into two cupped hands for oil

and paprika. The challah’s black sesame seeds

start moving, growing small legs and wings.

Shadowbeast with his new sloppy haircut

(loosed burrs) meows between the grape stalks

while the sheep, missing one lamb for the feast,

sleep early. This is where we ride out the apocalypse:

dodging the bug swarm brought on by a dozen

cross-referenced climate change issues (the burning

boundary waters, the too-warm winter) while we gather

to give thanks, to sip our wine buzzing

with bodies that we try to life-raft out

with our dry fingers, abundance (read:

black raspberries, okra shooting up

through its wilted flowers, Brussels bulging

on their stalks) surrounded by a flatland

of leached soil, oceans of corn, each stalk

producing one perfectly tired ear. In the middle,

this small resistance.

Members of the Mustard Seed Collective gather for a meal.

Then We Feast

by Benjamin DuBow

I am a third generation New York Jew–not exactly the type one might expect to find on the Mustard Seed Community Farm, a Catholic Worker organization in Boone County, Iowa. But if you think about it, it actually makes perfect sense. (Bio)diversity is a key component in regenerative agriculture, after all, and the emphasis of this organization seems more on the worker than the Catholic; insofar as religion comes in, it’s about love, mercy, kindness, and justice. And, of course, this farm is about food–so, yes, it does make sense I’m here.

The folks at the farm referred to it as an interfaith space, one where people from different backgrounds could come together in communal celebration. Since I got here in the summer of 2020, however, the pandemic had put all in-person events on hold. So, with the weather warming and the threat of infection receding with vaccines (a temporary reprieve, it turned out), I thought it might be nice to host a Shabbat dinner out on the grounds, among the plants that fed us.

The menu for the evening was perhaps a tad ambitious, but this was a celebration. An ode to the work we’ve put in and to the people who showed up. An ode to the land–drier than it should’ve been but still, miraculously, riotous with green, shouting the possibilities of collaboration. And an ode to community, and to this rest well-earned. Every item would feature at least one ingredient from the farm, of course, even if that was just a clove or two of amazingly flavorful garlic.

There was (egg) challah, of course. Eight loaves, by far my biggest batch yet, enough to feed the thirty to forty people who were joining this festive, holy meal. Then, for reasons both seasonal and personal, I decided to let the rest of the meal emerge from my roots, which run deep with love for Levantine food, and lean into the family-style smorgasbord of dips and salads–challah is especially good with dips–that feel so fitting for such gatherings.

Some dishes needed to be made days in advance, so their flavors had the chance to fully meld: the spicy green sch’ug (technically Yemenite, though by now a staple in Israeli cuisine), deep-red harissa (technically Magrebi, also spicy), and brick-red matboucha (also Maghrebi, likely originating in Morocco or Tunisia; Jews brought their recipes from all over the diaspora, and I guess what I’m trying to say is that there I was, doing it again, this time in Iowa). Other dishes, like the tabouli and the tomato salad and kefta mix, were best when given a few hours to marinate. And then there were some that had to be as fresh as possible, like the babaganoush, made from justfire-roasted eggplants after they’d been drained but still held heat. These last dishes I decided to prepare at the farm. I hoped it wouldn’t be too much trouble. I hoped everything would go smoothly, and I’d scarcely break a sweat, but realized that was unlikely. I planned to bring a change of clothes regardless.

For the mains, rice with dill (too much, in the end, and the large batch didn’t cook right, either. I took note for the future, and remembered that so much of this work, which begins with a vision–both in the field and in the kitchen–is always about revising and trying again), a lemony stew of chickpeas and greens (which turned an ugly brown; I probably should’ve used plain water rather than a stock, and let the lemon do the talking), garlic & herb potatoes (not as crispy as they want to be, given the lag between cooking and eating, but there was so much fresh rosemary and thyme and sage–all just plucked that morning–that it couldn’t possibly have turned out badly), and kefta kabob, torpedoes of ground meat enriched with herbs and spices. The meat was lamb–a lamb that had lived on the farm just the year before.

I cooked the kabob last, on a blazing hot woodfire not forty paces from where the surviving sheep grazed. I wondered if they smelled the aromatic smoke (some rosemary twigs thrown into the fire for added juju) and knew. I wondered how they had experienced the loss, and I wondered, perhaps naïvely & self-justifyingly, if they recognized how we were celebrating their brother’s life in the context of this local web of lives. I do know that, over a blazing-hot woodfire fueled by downed and pruned branches of chestnut and oak– trees beneath which this lamb whose flesh I now cooked likely once found shade–I tried my best to get those kebabs just right.

In Genesis 2:15, when Adam is settled in the Garden, his purpose is clear: the words used are הלשמר and הלעבד [le’shamra and le’avdah] and though the latter is commonly (universally, it seems) translated as “to till,” it shares a root with avodah, which can either mean work in general or else, more specifically, ritual service in the Temple of God. Perhaps this multivalence is not accidental. Perhaps it’s trying to tell us that the land, too, is Temple, that the earth is yet another manifestation of this spirit we call God. Perhaps the farm is a place of divine service, which would make this farmwork a form of worship. Surely it is a place that must be guarded, watched over, tended to with tenderness (le’shamra).

None of this is easy, of course. Which is why we have Shabbat, a day of rest. Shabbat is the reward for working all week long–the thing to look forward to. It is also, at the same time, the source of possibility–the day of rest that allows us to work the rest of the week. Ironic, then, that Shabbat preparation is itself so laborious. Or perhaps it’s not ironic, but shockingly appropriate. Eating, as Wendell Berry writes, is an agricultural act–and if the farm work which allows for our eating is hard (which it is), it’s fitting that the cooking should be demanding, too. By the sweat of your brow shall you get bread to eat, the Book says (Genesis 3:19).

There are no shortcuts. None worth the eating, anyway. None that celebrate this, here, now. The time came to gather around the table, set in a patch of grass between the honeyberries and the hazels. I saw my friends and coworkers sit; I saw the spread of dips and pairs of challah strewn down the length; I remembered what our work is all about. It’s about tending and service, yes, but it’s also about sharing. About community sharing a communion to celebrate the holy land that bears its fruit. And the picnic bugs camouflaged as black sesame that lost themselves among the seeds atop the challah, the ones we tried to pick off and shoo away, tired of all the pesky annoyances? We’d worked so hard to make things right, and these bugs seemed to be taunting us with their persistence, there in that unpoisoned place. But they, too, were part of it. God, I thought, they are so gross. God, I thought, they are so beautiful.

We raised our glasses, said l’chaim to the bugs, and ate.

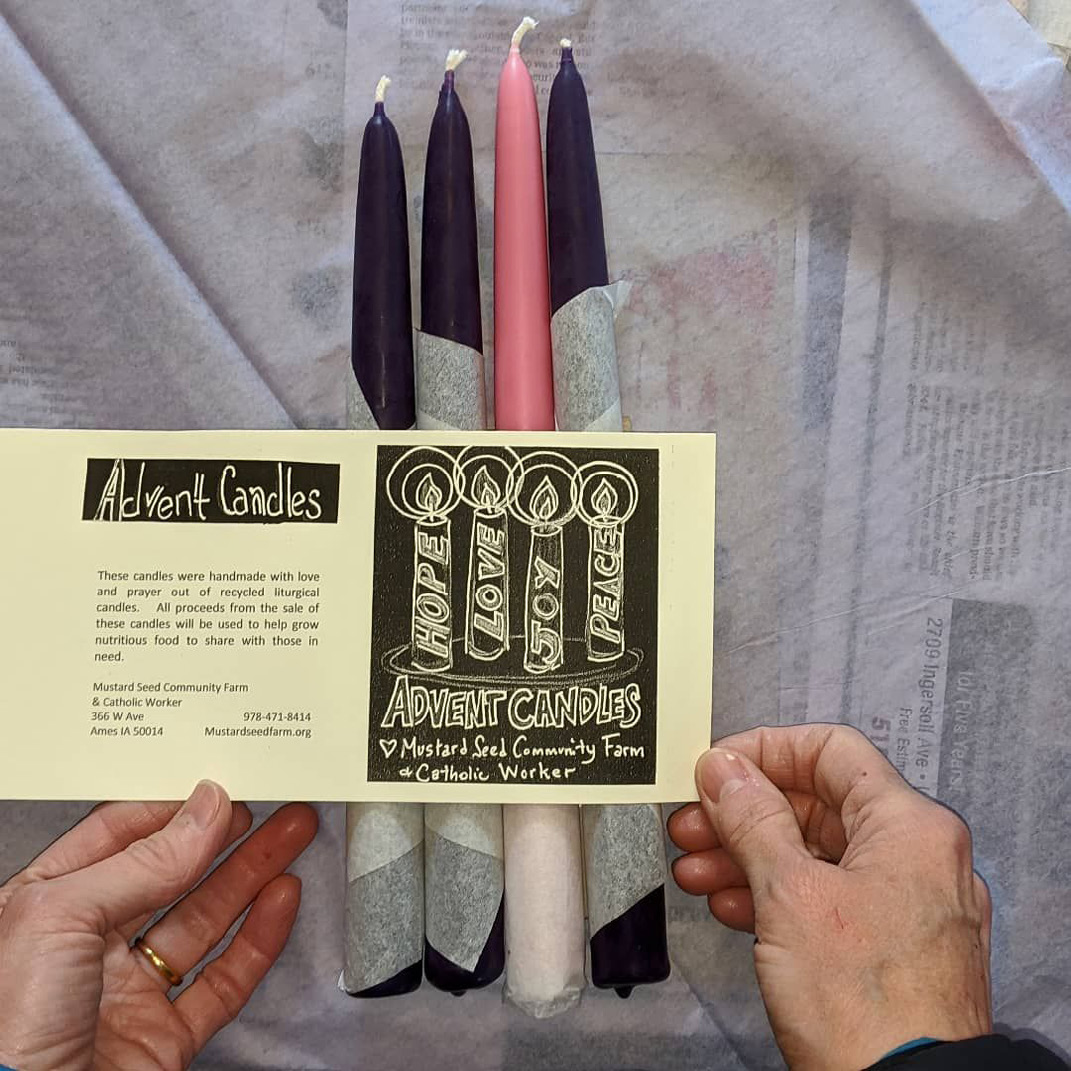

Making Candles

by Zoë Fay-Stindt

We haul the old ones down in crates

from the second floor to melt into new,

glistening gifts for the Advent, despite

our co-tired that seeped into the soil

while we were peeling yellow garlic.

She asks what I’m processing today

and I say, where the self ends and the rest

of the world begins. See? Cloudy mass

of nonsense. She answers, I don’t think

you’ll be able to answer that one before

the end of the semester, and we laugh, lower

the candles into bigger selves. Pink wax

accumulates around the anchors and Barb

snips them free. We call them raspberry donuts,

yum yum, says Alice, dropping them in the tins

to melt again. Nothing wasted. It’s a slow art,

this widening: eternal layers, wax building out

from inside, Russian dolls of pink, pink, pink.

Nate brings squares of chocolate peanut butter cake

for breakfast while the builders outside blast emo

punk-rock, re-siding the barn walls. Last week

Alice, worried the town would turn against her

for her art sabbatical, confided, I wonder if everyone

thinks we’re just loafing in the new buildings

the community helped pay for, and I want

to shake her, tender, to draw a bath or make

a firm bed for her. For the rest of the afternoon,

passing the wicks and their gathering mass

back and forth over their heated, bubbling tins,

I chide her: loafer. Hey, Alice, quit loafing

and help me with this set. We speak intentions,

prayers into the gathering wax. I say rest,

say listening, ease. Into the still-warm selves,

Alice asks for an end to exploitation

of land and bodies. For so long

I wanted to be known. To shout my voice

so loud it’d echo across the gone generations.

Now I think I’d like to be melted into this growing

chorus, lit in someone else’s home prayer

into enough, enough, enough. The room brims

with pink, glinting from glass-rippled sun,

lighting us possible again.

To Remember That We Love this Place

by Alice McGary

When I felt like I didn’t have anything wise to say, I went out to check on the greenhouse, on the little plants in this wild wind and bright sun, thinking about rural regeneration. I was thinking: remember that we love this place: this place, big and small, right here. This land and these people and creatures and water and soil. Our wider community, extending slowly wider to the whole world. It centered me in my mixed-up-ness, a hope for myself, for my community, for rural people everywhere, for all of us on this planet: to remember that we love is to remember why, but also how.

Poppies and Perseverance

by Amie Adams

One rainy, early-May morning, a crew of volunteers weeded along a row of grapes dense with lamb’s quarter, shepherd’s purse, pennycress. Woody grape vines twisted up metal posts. Beneath the fast-growing weeds, tender poppy leaves unfurled. “Pull it all up!” Alice said. “But not the grapes! Oh, or the poppies!” She bent down to show us the difference between the young poppies and the plants to remove, but I was inexperienced enough that I wasn’t sure I could reliably tell the difference. How much did it matter, really, if I pulled a few? They were so small, and surrounded by so many weedy companions, would they even make it to flowering? And on a cold, muddy day like this, there were more important things to do than protect the poppies– like warming my hands.

Weeks passed; tasks piled up. Each day we chose tasks from an ever-growing list. Mulch potato field. Trellis tomatoes. Wheel-hoe rodeo. Plant flowers. Finish grant application. Weed raspberries. Planting flowers didn’t seem like a priority when there were crops to weed, mulch, water, and harvest. But we did anyway, and in time poppies bloomed blush pink beneath the grapes and a rainbow of sunflowers and zinnias spread between rows of cabbage and celeriac.

At a midmorning meeting in September, another intern–Maggie–said. “You know, a few months ago, I thought planting flowers seemed like a waste of time. Especially when it seemed like there was always something more important to do. But I’ve seen how happy the flowers make everyone, and I’ve changed my mind.” Over in the rows of zinnias Jen smiled. Something profound and live-giving is growing in my soul. Because of Mustard Seed, I’m reviving a connection between my body and the ecosystem and watershed I inhabit. This place is changing me–literally–through the food I eat. I’ve cared for plants, made friends with people and cats, dipped candles, attended Shabbat, and witnessed connections form across divides that might otherwise separate us (ideological, species, you name it). I think I’m beginning to understand how to belong to a place.

Toward Faith and Banquets

by Zoë Fay-Stindt

We snip peppers and toss them (gentle–

how easily they break) into brightly

colored floppy tubs while Alice

tells me about her faith, how some worry

about her trust these pandemic days,

because she asks for masks, for distance

in the fields: where is your faith in God?

She wants to reroute excess. To stoke

abundance into enough for everyone.

We could at least try that first,

she says, checking the undergrowth

for hidden greens. In their neon pink

tubs, the peppers grow into small mountains.

Behind me, the raspberries have turned

into a dilapidated buffet for the picnic bugs,

who bury themselves four to a berry, turn

the thing sour with their spit. But there’s enough.

So much. Down the road, Food at First waves

bags of peppers away, the women’s shelter

slicing and dicing all autumn long, our counters

all mounded rich. For a flickering moment,

abundance feels possible, coaxed

by these tired hands.

In the summer of 2021, Emma Kieran Schaefer spent two weeks at Mustard Seed Community Farm as part of an art residency she was awarded through AgArts. During her time on the farm, she created a docuseries about the farm, and was also inspired to write the song, “Miracle Seed”.