*Author’s note: This story, a work of historical fiction, was inspired by the life and aeronautical innovations of Albert Ulysses Rupel, born in 1880 in Jay County, Indiana. He achieved much, including the building of an airplane in 1903, which flew successfully as a glider. He was working on its engine when he died young, from tetanus. (For a fuller account, see Eugene Gillum, “From the Ground Up,” Jay County Historical Society, Portland, Indiana, 2011.) There are many facts that could be underlined, such as the truth that the Wright brothers attended his funeral. However, my construction of his social life with neighbors, family and friends is, as far as I can know, fictional.

My name’s Chester Whitcomb Riley, named after our state poet, who wrote ‘’Little Orphant Annie” and “Waitin’ fer the Cat to Die,” my favorite, though I lack the knack fer pencilin out poems myself. My pals call me ‘Wick,’ short fer Whitcomb, say it like in a burnin candle ‘wick,’ guess cause I’m fired up fer the ladies. But this story’s not only about me, it’s about me and my best buddy Ulysses, leastways I called him Ulysses. Well, actually, I called him ‘U,’ as in ‘Hey You,’ that’s how ya say it, ‘You,’ just plain letter ‘U.’ But his full name when he come into this world—the eighth day of August 1880—in a long sorry labor on a 120-acre hog farm outside tiny Poling Town, Indiana, was Alexander Ulysses Kidd, christened so by his lovin mother, Myrtle May. She give him, she told me, the name Ulysses cause he come into the light at dawn, and she membered the schoolmarm’s homeroom recitation of the Odyssey, where Ulysses set out from dawn’s ‘rosy fingers’—way she membered it.

Then, too, Ulysses was General Grant’s known name, and Myrtle May’s own dad, Cletus O’Toole, had served under him—First Sergeant in the Battle of Shiloh— where he caught a minniball in his right leg, right above the kneecap. The ball stuck there fer all to see, she said, and he took sick and went to heaven, even though they had sawed the green part off. They buried him, along with his missin leg part, in high ground overlookin the White River, water’s edge fer Indianapolis back then. That monument there in Indy, fer the Union vets, she said she wants her dad’s name cut into it, cause he was a good pa—woulda been a great soldier, only he’d had more chance. She knowed, she said, her son Alexander Ulysses would be great, like Alexander the Great, since they was both born with one brown eye and one blue, difference bein one conquered the earth but her Alexander would conquer the sky. So there you have it, a Hoosier boy headed fer greatness, headed fer the stars— to fly like no man had ever done.

U studied hard in high school, just three of us in the whole class, seven in the whole Poling High School, that’s a fact. Me and U was the oldest, so we had duties. In winter, I’d stoke the stove with dry hickory, four-way splits about a foot-length out, and U would warsh the blackboard with bucket rags, makin sure at least one long length of chalk hid in the tray, fer the teacher to find. Before the lesson Miss Hearn, our teacher, would turn her backside to us, fiddle her gray bun, and square the overhead George Warshington pitcher. I reckoned that where President Warshington, the father of our country, was hung, that direction pointed north. Anyways, U studied birds and triangles whenever he could, I studied gettin up mornins in time to rob eggs from the hen nests in the hen house, then slow-footed it to school. Next to the school, a one-room house, was a water pump and a cherry tree, planted by the class of 1892, to honor George Warshington.

One May day, right when that cherry tree decided to blossom, a new student showed up, a girl, makin fer a class of four. Her dad did only popcorn, farmed the fields next to the schoolhouse, so it was easy fer her to get to school. Just hiked up her skirt, shinnied over the wire fence, careful not to catch her calico. Name of Beatrice, Beatrice Bettendorf. Bee—what we named her—was made to do the daily verse. U liked her versifyin, I liked her looks. She had the prettiest pigtails, blacker’en dirt. Her work apron fit her real nice. She helped teacher put out the lunch, too, skillet biscuits and fresh milk (from my dad’s cows).

The other girl in our class, Hazel Wilt, her dad did dairy, too—Holsteins. She griped the school didn’t serve up her pa’s milk. I said cause we had Guernsey’s, what give out better butter. Her pa come over to our dairy barn to poke our cows. Hazel come along but got bored lookin at udders. That’s when I walked her to our pig pond, to show her my prize porker, called General Sherman. “Why’d ya name him that?” she asked.

“Cause he eats up everthing in sight,” I said. That’s when she took my hand, over to the shade of the willow tree by the wallow. I give her a kiss, on the lips. She let me. I told U.

“Hazel cannot do long division,” said U. Both his eyes looked like clay marbles, the blue one more glazed. It drilled right into me.

“Might be, “I said, “but she looks made for milkin.”

Pretty soon, the township shut our high school down, eight students not bein sufficient. That made U mad, since he reckoned on doin higher sums. He knowed he really needed more rithmetic fer his flyin projects, so he went back with the eighth-graders to do-over the drills. He liked do-overs, said it left the lessons in your noggin, like a photo-somethin, it was. He did that Greek theory over and over on his chalkboard. After school he bagged birds with his squirrel rifle, a handy one-shot .22 Remington. Pigeons it was, shot them off the beam over the hayloft. Once he had hold of a dead pigeon he’d chop it up with his jackknife, turnin over drawins in a bird book, pickin at its guts, measurin its wings. Saturday mornins he watched white pigeons waddle around the chicken coop, peckin at bits of gravel, just gettin off the ground after a wobble, barely clearin the barn or not, when they got brained. He liked to look at the white ones, he said, cause he supposed angels had white wings, too.

“Why do pigeons fly so badly?” U asked me.

“They ain’t angels,” I said.

“Don’t make a joke.” U’s face went red.

“Why ya wanna know?” U always had to ask me trick questions.

“You know why, Wick.” He pushed out his knobby chin, his signal for wrasslin.

“Ya wanna fly like a bird?” I flapped my arms like a goose.

“I want to fly high and mighty,” he said, as he tossed me one of his Flyin Eagle pennies he kept around.

With no high schoolin left, we had time to loaf, leastwise after chores. But when you’re goin on eighteen years of age you got lots of vinegar, so our loafin kept us movin. We’d go to my dad’s barn, unhitch the big Belgians and race ‘em, slow as they was. On scorchers we’d swim in the crick, below the barn, just before the stand of sycamores. Sometimes we’d rig sulkies and go all the eleven miles to the county seat, Portland, where we shot eight-ball penny a rack at Klemmer’s Pool Hall. Myrtle May got in a stitch over that, specially since she smelled tobacco on us. U didn’t take tobacco but I did, chewed Mail Pouch, just like my dad. I liked this loafin around, but mostly I liked girls. I’d roam farm-to-farm askin to help with the plantin and such, farms with daughters not in school no more, daughters who heaped up the mashed potatas, piled the fried chicken, set out the pies—rhubarb fer me cause it bit.

Another way I’d meet girls was durin detasslin corn time, July, maybe August. Once me and Priscilla Gablehanger went to pull the same tassle top and one thing led to another. Like I told U, “Before I knowed what fer she had her hand on my dogwood.”

“What did you do then, farm boy?” asked U. He never did take to such tales.

“Not ’nuff. The corn rows was all scratchy, no layin down.”

“I do not have time for girls,” U said. Truth told, he didn’t have time for farmin, neither. Walkin the beans in late summer fer pocket money was about it. Most of all he hated to slop the hogs out by the horse tank, the bristly red Durocs he had to feed the kitchen scraps, keep their pen shoveled clean. When I tell my brother Jake he keeps our sleepin porch like a pigpen, I know what I’m sayin. Pig shit, now that’s somethin U knowed he didn’t like. Who wouldn’ta knowed that?

But he also knowed somethin peculiar. He wanted to fly. He had to fly. He sent away fer an advanced study course—Engine Mechanicals—from Anthony Wayne Technical Correspondence School, out of Fort Wayne, some fifty miles from here.

He was puffed up about the course one day and we went to tell his ma. Myrtle May stood over a tin tub in the kitchen, a barlow knife in her hand, diggin caterpillars out of a head of cabbage. We sat on the edge of the table, chompin corn bread and strawberry jam. All at once, U swallered his corn bread hard then declared, “Ma, I want to build a machine that flies, beat those Wright boys to it.” The cords in his neck got tighter, like he was reinin in his words.

“Machines don’t fly, son, they run,” said Myrtle May. Then she snapped shut the jam lid before she spoke. “But yer blue birth eye has got you lookin at the sky.”

“Got to make the right engine, Ma.” U had his peepers on the flypaper danglin from the ceilin.

“Ya was born to greatness, Alexander.” She put her hand over her heart.

Ulysses dropped his towhead, his big curls bobbin. Then he stood dumb, like a statue.

“My Eastern star,” she said, studyin the jam mess we made and thinkin, I reckon, about his tomorrow.

“I’ll fly you to the sky, Ma,” he said, sightin a fat summer cloud with his thumb.

“Just mind ya don’t come to harm, son.”

Startin June first 1902, I daily drove U in a two-seater buggy—sometimes his dad’s, sometimes his own— over to Berne to the postal station, seven miles by the markers, so’s to see if the worksheets from his study course had come. On the twentieth of June, with red clover full in the culverts, the clover smell smotherin the smell of the horse turds, the worksheets got delivered from Fort Wayne, wrapped in gray pulp paper, all covered in green George Warshington two-cent stamps. On the buggy ride back to Poling Town, I said, “U, ya goin on the hayride this evenin?”

“No. You go.” He lifted his heavy head up from fussin with the worksheets.

“Bee wants ya to go with.”

“She knows Latin. We do declensions together. You go with Bee.”

“I take to Bee but she don’t take to me. She likes the great Ulysses.” I shouldn’ta said it sharp like that, but I did. “Sides, I’m goin with Sadie Yoder.”

“The Amish girl?”

“Yeah, heard tell they dance bare-nekked in the rain.”

“That all you care about?”

I cared considerable about Bee, but I didn’t say so. “Bee’s got the eye fer ya, U.”

“I have got to build an engine, a flying engine.” He lost himself starin over toward the sun, settin just then.

U begun his flight trainin for real. His engine studies showed him stuff the Wright brothers were workin on. Ah course, since Wilbur was born in the next county, that got his competitive blood goin. He wanted to be first, Hoosier first. In his attic room, on his bed quilt, he dumped out the study package, saw a leather lesson book and its ‘question pages,’ each startin with a commandment, like “Think. Do not simply recollect or repeat.” U saw the wherefer of that, saw that memorizin weren’t ‘nuff. He spread out the first-week packet, thinkin on new words: fasteners, sealants, gaskets; magnetism, cycles and components. The next week, he thunk on fuel lines, air induction, ignition. The third week, it were engine disassembly, cylinders, valves. Before long, he started goin to Smitty’s, the blacksmith shop on Boundary Pike, and buildin small gasoline engines for bike pumps, butter churns, and ringer warshers. After that, he made a thrashin machine engine, not small a’tall. Engine exercises, he called ‘em.

Engines was the cat’s whiskers in these Hoosier parts—the gas boom in Gas City, backyard strikes of oil, Elwood Haynes the inventor of the first automobile nearby in Portland. But U didn’t care about any kind of engines except winged engines. He turned his brain to the workins of how to fly, called, aerodynam-somethin. He hammered together kites that got tore up in Myrtle May’s clothes line. She made him stop that. Then, he did model airplanes out of horse glue and balin wire, stretches of shaved hickory for wings. He’d hurdle through the waves of green timothy, pullin eight-foot wings with binder twine. The tall grass cut his arms but it didn’t matter to U. Once one of these model planes caught a hot air patch and shot up, landin after twenty-seven seconds ‘without incident’ as U bragged to the neighbors watchin from the Back Forty. On a fencepost next to me sat Bee, purty as a picture and payin me no mind. She was all out for U, hollerin and hollerin. He heard her voice and froze her face when he shot her a wink.

That was a big day fer U, but it liked to make me feel small. All I had was a stockboy job stackin boxes at Ross’s Dry Goods in Bryant. Well, it weren’t all I had. I could eat penny candy till my dad’s cows come home. Tootsie Rolls mornin, night, and noon. They busted my gut. I et lots of licorice twists fer that. Plus, the owner’s daughter, Crystal Caster, took a shine to me. She worked the yard table, rollin out bolts of cloth, markin em for dresses. Like I told U, pretty soon she got hold of my bolt, back where they stored the feed sacks. U thought I shoulda been more of a gentleman. Maybe he preached that way cause he’d started with Bee, a lady I’d give my own heart.

U was her hero. She baked him cherry pies—gold lard crust laid on like a picket fence—and made a pine box fer his draftin pencils. She took piano lessons from Widow Jones, best teacher in the county, so’s to play keyboard fer him, even sing Saturdays. U fancied her, but he didn’t do nothin much about it cause of his dream. That give me a try with Bee, when U wudn’t lookin, him busy makin a bigger plane, a bigger engine, to lift him to the sky. He went on and on about wings of angle iron, ribs of steel, billy goat skin.

One hot sticky mornin, of a Sunday when the church bells was clangin, he was ready, and so was I. We took a hay rope, hooked it to the flying contraption—named ‘Blind Pig’— then latched the other end to his uncle Earl’s car fender. U drove the car, clutched it to top thirty-five miles per, when it stopped dead. U cut loose the rope and the glider flew up over the pasture like from a slingshot, waggin its wings like Taft’s top hat, before comin down buryin its wheels into the mud. U jumped out the car and pushed hard on a stuck wheel. He had nature’s own strength, like he was born a bear. It got unstuck sorta, then fell back, right on his left foot. Four toes crushed. Bee was there, standin tall and fine in the alfalfa, and saw it all.

Luck saved his big toe, the others didn’t wiggle no more. Bee cried like a bobcat caught in a mole trap. She cycled over to his home place ever night after fer days and days, to rub his foot and soak his toes in Epsom salts. Didn’t make no difference. She wanted him whole. One night I was there whittlin on the front porch swing, heard ’em wooin in the parlor, after she had sung to him about pickin violets in spring. It tore me up.

“Ulysses,” said Bee.

“Yes?” said U.

“Your toes. I prayed. I’m prayin yet.”

“Well, the big one works.” U never let on his pain.

“You are brave. They have to hurt.” She whimpered.

“Best get back to Smitty’s.”

“You’re my flyboy, Ulysses— all the way to the moon.” I heard Bee move, like her dress was swishin. Then the rocker rocked more. I tried not to listen.

Bee kept her faith, in U and the Lord Almighty. At the Church Social, she showed strong, sipped her lemonade. I watched her paint a valentine on the cool wet of the pitcher, put in it ‘B + U.’ Then she went all still. U’s ma, Myrtle May, had went gray with worry over the harm he could come to. She turned poorly, took too many nips of Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. U told me she kept the syrup on that walnut chest-o’-drawers in the pantry, next to them cans of lard. He told Bee and Myrtle May he knowed it would all work out cause—like he said—he could do what had to be done. He rose up like a gladiator, ready for the lions.

The rest of the summer, U pounded and banged. He built a gliding plane, wide as twenty farmhands standin side by side. Also, he hammered on a big engine, six cylinders. Winter settled in, frost froze its fuel. He parked that whopper of a flyin machine in Cheever Tate’s main storage barn, covered the engine in sheep’s wool. With spring a thaw come on. The bog sprouted lily pads, the toads hopped out their holes. Once the dandelions yellowed up, he knowed he could try again. When the wind was right, he could try his glider. It would fly high, then he would mount the engine and shoot for the stars.

The Weekly Commercial Review put out a broadside—“Poling Man to Fly”—advertisin over three Indiana counties—Jay, Blackford, and Randolph—not to mention nearby Ohio counties, includin Dayton. Lots of folks puttin money down, talkin about an “airplane.” One late May day of 1903, circled by young’uns playin Ring-Around-The-Rosie, me and U hitched four two-thousand-pound Clydesdales to the Blind Pig II, in Laff Lybarger’s high-ground field, where we’d been practicin. Word went out the township, and spectators, eighty-seven by one count, showed up, ready to roar fer U. They hooted and hooted, louder and louder, once the horses started jinglin and snortin. The team, the finest in Eastern Indiana, belonged to Harry Hardroe from out Winchester way.

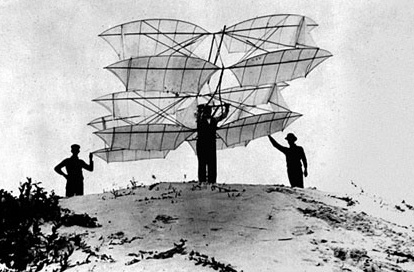

Franco-American aviator Octave Chanute (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octave_Chanute) prepares to launch his “Katydid,” a twelve-wing glider of his own design, near Gary, Indiana in the summer of 1896. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Harry shooed the ornery kids with the flat end of his whip. At ten o’clock on the dot, the sun breakin full over the last daffodils, Harry slapped the lead horse on his haunches, makin ’em all thunder acrost the rotted fall cornstalks. These broad beasts, chestnut chests full of pant, did not fall, did not falter, hoofs rising and falling in a rural reel. The Blind Pig II did rise, too, U riding the glider as it got hauled along. When it climbed high as the cottonwood tops he waved to Bee, who fixed a love look on him. I couldn’t see much of it cause of her parasol. Then the glider lost the pocket and it drifted down just past County Road 47, missin a silo, missin the gravel pit, but finally stopped, twistin in the Gibsons’ bramble bushes.

Fer no reason, when the plane plowed into the brambles, the crowd rose up a hymn, a hymn everbody knowed. U’s aunt Marthy, most particular, belted it out: ‘Oh come, come, come, come, come to the church by the wildwood….’ After she took a breath, Norval Reidenbach, U’s neighbor from the farm over, said, “Guess U was right, people fly better’n pigeons.” Everbody got a laugh. Next thing I knowed, a bunch of young fellas yanked U’s red bandana off his neck, hoisted him out of the plane, heaved him on a wagon bed, where the Clydesdales was hitched. Harry beat his belly like a drum, drove his team and U all the way to the Lob Lolly General Store, everbody yellin and throwin cattails and cow pies at U from the ditch. At the Lob Lolly, Issac Brown—the proprietor— give him free pickles, many as he could eat. Bee had been waitin for him in the store, over by the laundry soap. When U waved her over to the pickle barrel, she went all pink. I coulda done with some of that color.

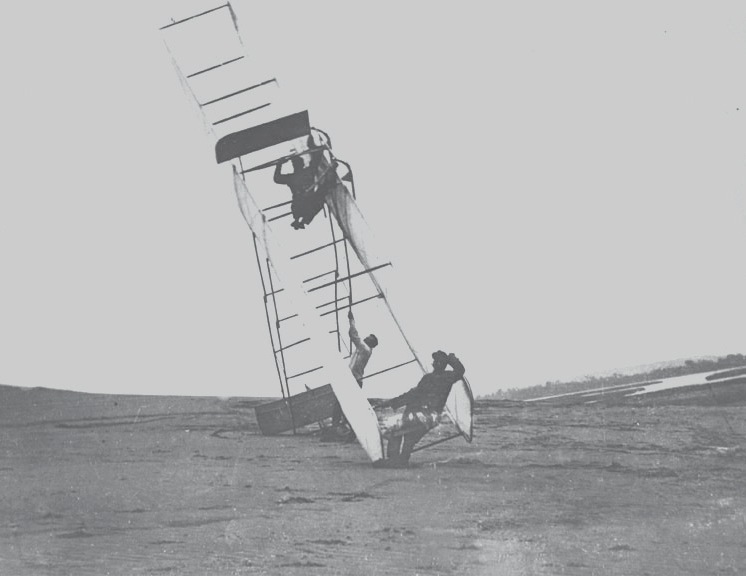

makes a flight attempt in 1895. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2022-spring/Lewis-beck-2.png)

German aviation pioneer Otto Lillienthal makes a flight attempt in 1895. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The way back home on my buckboard I felt grouchy as a bull with a pug ass, like dad would say. I was plumb wore out from handlin the glider and the horses, and my butt was plain sore. U was full of hisself. “That crate flies, Wick. I can fly! The people cheered me. You see Bee’s face?!”

“I did,” I said. “She’s moonstruck fer her man.” I didn’t say that no one wasted a word or a wink my direction, cept when Bee yelped at me fer steppin on her Sunday shoes.

We bounced the rest of the way, keepin to ourselves, till the smell of a dead skunk hit us at Gallager’s Swamp. “Pee-yew!” said U. “Worse than your farts.” I’d never heard U talk like that before.

U knowed now the contraption was sky-worthy, would fly fine. All it needed was his guidin hand, him at the helm, with the right engine at his fingertips, to power the propellers. He set about finishin the engine— just a four-banger for better size, with air-holes, to fit tight under his seat. Time was runnin out. I heard tell Sarah Worth, the Wright boys’ cousin in Bryant, had wrote’m about U and his flyin notions. So U had to double up. Slavin long hours, mostly by kerosene, forgettin his farm chores, he bunked out at Smitty’s on an army cot, up at dawn. U told me Bee would bring him bacon and egg sandwiches at noon, then split an apple with him, before he walked her back to the gate. He didn’t tell me what they did there.

The mornin of the eighth day of August 1903, his twenty-third birthday, hammerin away to finish the pilot seat, he turned to grab a board from the wood bin. He slid out a slat had a nail in it, halfway. His left-hand, his workin hand, gripped into the nail. He yelled out and Smitty come, wrapped a piece of burlap around it, and trotted him to Doc Gillum. Smitty collared me to go over to Doc’s place and wait with U.

Doc pulled the board up and the nail come with it, out of U’s hand. U turned white, a white stone. Somethin to watch. He doctored U, I bundled him home. A few days later, when I went to his attic hideout, it was 99 degrees fairinhight. “I can’t get him downstairs,” Myrtle May said, as she warshed his face with cool well water. “Feel his forehead, hotter’n this attic.” I put my palm on his temple. It liked to burn me. I heard Bee’s voice, comin up the steps, wailin like a widow-woman.

When she swung open the door, she changed. “Wick, get out of the way. Myrtle, please fetch me some washrags and that bottle of witch hazel. Let me take out that attic window.” She knocked loose the window jam and air come in.

“I’ll ride over get the Doc back,” I said.

Doc Gillum diagnosed, “tetanus—incurable.” That learned me two words I’d never forget. I confess I could hardly hold up. Ever day I went over and rubbed U’s arms, told him how we was gonna go up again, get them gas gliders goin. Sometimes he didn’t know me, would cuss me out. He was better with Bee. She cooed and warshed his eyes with cold water, one at a time, first blue then brown, back and forth. A true special lady. Next thing, afer we knowed it, his neck don’t turn, his face twisted up like a Halloween mask, couldn’t even keep down Myrtle May’s special chicken soup. His jaw locked like a vise, and he’d have crazy man fits. U died a week later. Without U to horse around with, I was a blank slug. Mostly, I just swigged Old Crow.

The funeral service, held at Bear Creek Methodist, brought folks from five Indiana counties, and next door—Ohio— counties. Even the Wright brothers made the trip. They’d been meanin to get to Poling Town ever since cousin Sarah had wrote about her neighbor—the boy ‘Born to Fly,’ she’d put it. Now they come, Orville and Wilbur, as pallbearers, sad to say. Their testimony got to the mourners and the church choir salved ‘em by repeated rounds of “Rock of Ages.” ‘Rock of ages, cleft for me/Let me hide myself in Thee…’ During everthin, Bee kept a distance, upright under the shade of an old oak, in a black dress. She didn’t have nothin on her head or face. I wanted to talk to her but I couldn’t.

After the mourners had gone, I stood over the grave. I took off my itchy collar, rolled up my sleeves, reached in my tote and pulled out a pigeon, a dead white one, put it on the grave dirt. U had finally flown better’n a pigeon, just as he was born to. My best buddy winged his way to the Pearly Gates. I wandered off into a field of corn, summer sweet, like U and I had done ever August, before start of school. U never got sick from it, I always did. I et one ear raw, then shucked another and et it, and another, till I got a powerful bellyache.

At Christmastime, the August heat made for a distant memory. The ground froze, the cornstalks hard stubble, the fields dusted with snow. I stumbled over clods of soil, crost a field onto the Kidd place, went to a grove of pines, chopped one down with my axe, tied it to my buggy, and took it over to Bee’s. She saw me tetherin my pony by the root cellar and waved me up to the house. I dragged the tree to the parlor, stuck it in a warsh tub next to the wide window overlookin the road. She put a tinsel star on the top, one she’d made for U. She cried till she couldn’t cry no more. I felt too low to cry. I had felt too low to even come see Bee, to my shame. Here I was now, to make a try.

“Bee, our U’s gone, gone almost six months,” I said.

“Yes, over the moon, he is. More like four months. One-hundred-and-thirteen days, actually,” said Bee.

“Seems longer.”

“Seems like my lifetime.” With bony fingers, she tugged at her gingham dress, liked to wipe off the black-and-white checks. She said nothin else, just stroked her dress.

“When ya lost U, Bee, ya lost yer world. I lost mine, too. Now we got nothin left but our feelins for U. A candle still burnin.” I got up out my straight-backed chair and went down on one knee. “Will you marry me?” .

Bee went back to her scissors and thread, her thimble, went to the davenport, returned to the string of popcorn she had been workin on.

“No, Chester. Thank you. No.”

Day after New Year’s I left the farm and Poling Town, moved into Portland, got a room over Klofenstein’s Hardware, paid the rent by sweepin the store. Didn’t feel much like chasin the ladies, not since Bee. I did run into her at Stabler’s Drug. She said she’d quit the farm to work at the county courthouse, acrost the alley. Put up a museum there—stuffed owls, arrowheads, gas lights, old maps, carved canes, soldier medals, toads in jars. I visited it once. They was bird wings, all sorts, wings from hawks, pheasants, larks, robins, jays, crows, chickens—you name it, except for pigeons. A piece, too, of wooden wing from the Blind Pig II, with a label she sewed on. It said, Alexander Ulysses: Conqueror of the Sky. Myrtle May never did see it. She did tell me once that on U’s birthday she read aloud over his grave, from the Dayton Daily News, the big story about Orville and Wilbur Wright. “The headline says ‘First in Flight.’ We know better.” I didn’t have the heart to say otherwise.

Orville Wright crashes one of the early Wright Flyers at Kitty Hawk, NC, in 1911. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Wright Brothers’ first successful flight, December 17, 1903. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.