I am obsessed with fly fishing for trout. In Iowa, trout are only found in far northeastern Iowa streams. When weather and water conditions are favorable for catching fish, I make every effort to get to one of my favorite Iowa trout waters, tolerating the 340-mile round trip for a day of fishing. I will fish long hours in the heat or cold any time of year; I will walk far and work hard for the chance to catch trout. I target unstocked sections of streams or tough areas with difficult access to find water with limited pressure, which often improves my chances for success. I’ve only fished trout for ten years, using spinning tackle and artificial lures for four years before taking up fly fishing. During this time, I’ve worked diligently to improve my trout angling skills, dedicating countless hours to bettering myself. It has been a labor of love to pursue trout in this beautiful part of the state.

Nymphs imitate the immature larval stage of aquatic insects, like caddisflies and mayflies, and subaquatic species, like worms, scuds, and leeches. Nymphs can be drifted to fish with a tight line presentation using “sighter” line to detect strikes or with any form of strike indicator attached to the line functioning like a bobber. This aids the fisherman in determining if a fish is interested in the bait and, if lucky, if a fish has taken the bait. Dry flies imitate mature adult insects, including many kinds of stream flies and terrestrial insects, like grasshoppers and beetles. Dry flies are cast directly to the surface-feeding fish or drifted to fish using stream current. Streamers imitate small baitfish and crawfish and are fished with an active retrieve by pulling line in quickly.

Fly fishing requires a myriad of gear and accessories, and between fishing trips it is critical to spend time at home keeping it all in good working condition and organized. Quality waders and wading boots, fly rods and reels, and nets are essential. A good vest or pack is required to hold everything within easy reach that could possibly be needed streamside. The weather dictates clothing needed, and a change of clothes is a good idea, as wading accidents will occur. I stay connected to fly fishing by reading and rereading classic fly fishing literature, with a book always open on the nightstand. Indeed, it is virtually my only reading done for pleasure. YouTube provides me with hours and hours of fly-tying instruction, fly fishing how-tos, and awesome fly fishing adventures from around the world. I have always liked to fish. It seems now I live to fish.

To stay connected to fly fishing when at home, I tie all my own flies: nymphs, dry flies, and streamers. Additionally, I make all my own leaders, which primarily protect the main fishing line from damage and breaking, by fastening 20-pound test camouflaged monofilament to my fly line. And, tying progressively smaller diameter camo monofilament together forms the taper to a short section of brightly colored or bicolored monofilament that makes strike detection visible to the wielder. To finish it off, the tippet then connects to this “sighter” line, allowing flies to be attached to the leader. Because in Iowa we are allowed to fish two flies per line, I tie a new two fly tippet and prepare some spares at home prior to the next fishing trip.

Driving into northeast Iowa, one sees and begins to feel a change come over the landscape. The land is more rugged and roads are no longer oriented north to south and east to west as is common in the rest of Iowa. They switch back and snake along stream valleys and over ridgetops. Agricultural fields of northeast Iowa often are contour farmed, and the large, rectangular farm fields common to much of the state are replaced by fields in seemingly limitless shapes and sizes. The timber thickens and the steep, inaccessible ridgetops create a sense of remoteness and ancientness. Even driving, you imagine yourself in a remote ridgetop timber beneath the dense canopy, planted on the sun-starved forest floor. In appearance, the contrast that this area provides to the rest of Iowa is remarkable.

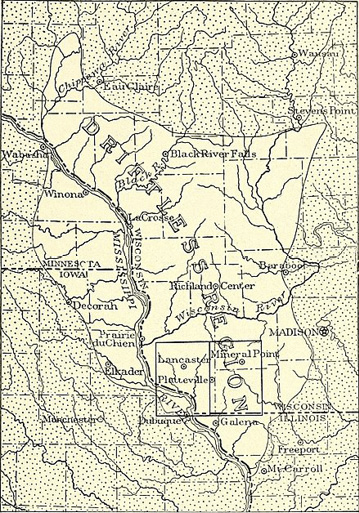

1911 map of the Driftless region{{% ref 1 %}} of Iowa and Wisconsin.{{% ref 1 %}}

During this drive to Decorah’s Pulpit Rock Campground for a three-day fishing and camping trip with Diane, my wife, and our friends Steve and Lisa, I think about why this particular trip seems so important to me. Perhaps I just need to get away and try to forget about things. It has been hard not to dwell on our country’s intensely polarized political climate fueled by rampant misinformation, our resulting dysfunctional government, and the ongoing threat to our democracy. The long-lasting pandemic, with so many in our nation more concerned about their individual rights rather than for the greater good of others, provides little hope for the immediate future. Affecting my family very directly, the death of my mother to pancreatic cancer in summer 2020, and my father’s terminal liver cancer diagnosis in summer 2021 has taken an emotional toll on my sisters and me. We are nearly two weeks into Hospice home care for dad, and he isn’t doing well. I have been apprehensive about what lay ahead for him and the end-of-life decisions we will again be facing.

The past two years have been difficult for me. I find myself regularly distracted, anxious, and impatient. I’ve often commented that it seems the only thing that has gone well for me during this time is fly fishing. Maybe this trip is important because I am just looking forward to fishing. I get completely absorbed in the moment, clearing my mind and focusing only on the task at hand—catching the next fish. For me, trout fishing is peaceful and calming, and I am grateful for the solace found on trout waters. Between dad’s health and my work, I have had little opportunity to fish since mid-summer, but I am thankful for the time spent over the past few months with dad and my sisters and hope to return home with at least some renewed faith and optimism for the future.

I began fishing with my dad as a very young boy. Dad taught me about fishing equipment, how to find and use live bait and what to use for artificial bait, how to locate and catch fish, and how to clean fish and prepare them for the table. We fished ponds, Big Creek Lake, and the Des Moines River catching bluegill, bass, crappie, and catfish near our home in central Iowa. Dad would often share helpful insight when I couldn’t get fish to bite, telling me I wasn’t holding my mouth right. Or, when a fish would strike and I couldn’t hook it, he would tell me that I really missed that one. He seldom fished as he got older, and Dad never fished for trout.

Trout fishing in northeast Iowa is excellent, and anglers can fish year-round with no closed season. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources keeps the streams well stocked with ten to thirteen inch put-and-take rainbow trout. The spring-spawning “Rainbows” don’t reproduce naturally here. However, rainbow trout tolerate the hatchery conditions far better than brown and brook trout and thus are much easier and more economical to produce. In Iowa streams, fall-spawning brown trout are now reproducing naturally, providing self-sustaining populations that produce good numbers of fish. Because of this sustainability, there are no plans to continue to stock brown trout in Iowa streams. Brook trout also are fall-spawners and the state’s only native trout. Due to their more specific spawning and habitat requirements, particularly cold, clean, high-quality water, “Brookies” reproduce and thrive only in a select few streams. Brook trout are stocked only as two-inch fingerlings in area streams with habitats conducive to their reproduction and survival.

The Driftless Area, which people there simply refer to as the Driftless, comprises southwest Wisconsin, southeast Minnesota, northeast Iowa and a small section of far northwest Illinois. Approximately, 85 percent of the Driftless is found in the southwest quarter of Wisconsin. This area was not covered by ice sheets during the fourth, final Pleistocene glaciation called the Wisconsin Glacial Advance. Because of this isolation, the Driftless lacks drift: the clay, silt, sand, gravel, and boulders left behind by the receding glaciers. Common landscape features of the Driftless include steep hills and bluffs, called Coulees in Wisconsin, thickly forested ridges, deeply gouged streams and river valleys, karst topography, and the heavily fractured bedrock of limestone that surface water flows through to erode and form caves, disappearing streams, surface water sinks called sinkholes, shallow ground aquifers, and underground streams that often resurface as cold-water springs. These springs supply the cold, clear, oxygenated water to area streams. This high-quality water combined with the limestone dominated stream beds and their variable stream bed composition, flow gradients, and water depths provide the habitat trout need and the support for plant and insect life that trout depend on. Trout live in beautiful places, and the Driftless is a beautiful land of diverse habitats: a topographical island in the otherwise flattened Midwest landscape.

On Sunday, the last day of our three-day camping and fishing trip, Steve and I leave the campground well before sunrise on a gorgeous mid-October morning in the Driftless. It is warm with a light breeze and the many visible stars tell us that we will be seeing the sun at sunrise. We are heading to Waterloo Creek to fish the restrictive, regulated stream section that mandates catch and release of all fish and only artificial lures. Catch and release angling usually eliminates the need for put-and-take stream stocking programs, and results in larger, “wilder” trout better adapted for long term survival in the streams. I practice catch and release when trout fishing, releasing all brown and brook trout netted and only occasionally taking for the table put-and-take rainbow trout. The use of artificial lures is much safer for the trout than fishing with live bait. Fish tend to swallow live bait, and the hooks are usually impossible to remove without injuring or killing the fish. I always use barbless hooks on the flies I hand tie. They are much easier to remove and thus inflict little damage to fish.

We were hoping to be the first anglers to the parking lot, but a wrong turn ended up taking us well out of the way and cutting into our precious angling time. Checkout time at the campground would be 1:00 p.m., and Steve and I figured we would need to be off the stream and heading for my truck by 10 a.m. We got to the stream parking lot as the sun below the horizon began to illuminate the eastern sky. The parking lot was empty, thankfully, and Steve and I rigged up our fly rods and put on our waders and boots.

We crossed the stream near the parking lot and found the water to be very clear and at normal level. The dry summer and fall had led to reduced stream flows and very clear water that had made fishing challenging. Despite these conditions, Steve and I had enjoyed the usual good fishing on South Bear Creek on Friday, catching a mix of brown and rainbow trout in good numbers, but nothing big. We found the fishing at Coon Creek Saturday morning slow, catching only several rainbow trout and many very small brown trout. I fished Twin Springs Creek right behind our campsite Saturday afternoon and had great fun catching many rainbow trout from the shallow, clear water. As Steve and I hiked downstream at Waterloo Creek, two bald eagles flew upstream, apparently also starting their fishing day. Bald eagles are commonly seen in the Driftless, often trying to catch trout. Just as we got to the stream, the sun topped the bluffs to the southeast, and the morning’s first golden sunlight danced on the stream’s broken surface.

Steve and I had been catching fish all morning, including a nice 15-inch brown trout just hooked and landed. I consider any Driftless trout 15 inches or larger a good fish, and we remained optimistic that we may yet find a big fish in the great looking water upstream. I checked my phone, and it would soon be 10 a.m. and time for us to head to the truck. Steve stayed to fish just downstream of the deep corner pool fed by a fast, shallow riffle with the fastest water flowing closer to the far bank and hard around the corner. The deepest, darkest water of the pool was between the faster water and the shallow gravel bar where I positioned myself. Because of the bright sunlight and gin-clear water, I expected the best fish in the pool to be holding in the deepest water and where the current moved food directly to them.

I cast my hand-tied, tungsten bead-headed pine squirrel leech fly upstream and across into the faster water and let it drift downstream. The fly stayed in the shallower, faster water along the far bank and around the corner—not the drift I or a hungry fish wanted. I placed the next cast upstream right at the inside seam between faster and slower water. The fly rode the current downstream, but this time found the slower water at the top of the pool and sank quickly into deep water. I fished the fly slowly, felt a slight tap, set the hook, but no fish. The next cast repeated the same drift and as the fly again settled into the slower, deep water, I felt a solid take and responded quickly with a downstream hookset. I instantly found myself fast to a good, heavy fish that took line easily even though swimming upstream into fast current. Not liking the shallow water it found there, the big trout turned back downstream making for the deep corner pool, content to settle this fight in the deepest water with violent head shakes and short runs.

My heart pounded from excitement during the difficult, lengthy battle with the fish and from the fear of potentially losing it. I remember last year in this same stream section, when I broke off a very large brown trout. That memory haunts me. Though my angling skills continue to improve, and I’ve become a more confident angler and have netted progressively larger trout with each fly fishing season, I wasn’t certain I’d net this fish. Keeping steady pressure on it by slowly backing downstream, I took line when possible and allowed line to be pulled off the reel during the fish’s frequent runs. Eventually, I worked the big fish close enough to determine it was a large, male brown trout, and it appeared to be hooked solidly in one corner of its mouth. After making it to a shallow spot to net the fish, I held my ground and slowly worked the big brown trout towards me. My first attempt to net the fish was a failure. It spooked as I extended my net and made its last long run to the far bank, tiring as I worked him ever so slowly back towards me. The second net attempt was successful, and with the great brown trout in hand, I was an elated fisherman. After a few hollers and high fives, I easily removed the barbless hook, and Steve and I worked quickly to get a few more photos, measure its length, and release the great brown trout unharmed back to the stream, perhaps one day again to be caught by another lucky Driftless angler.

The beautiful male brown trout measured twenty-one inches long, and due to the thickness and height of its body, I estimated that it weighed well over four pounds. The photos show its big square tail and huge, bright sunflower yellow fins, a distinctive kyped jaw, and a stunningly beautiful, dark olive spotted back and bright golden spotted sides that transitioned to its amber underbelly. I am thankful to have had the chance to hook, land, and release such a wonderful Iowa Driftless brown trout, and to have shared this experience with my fishing buddy. The pictures he took really capture the beauty of that fish and the stream that is its home. My goal over the past three fishing seasons has been to land a twenty-inch brown trout because I hadn’t caught one previously, and fish that size are not all that common in Iowa’s Driftless streams. During this quest for the twenty-inch brown trout, I caught several dozen fish over sixteen inches with a few fish topping nineteen inches. However, all those fish paled in comparison to the size and beauty of the brown trout in this story. My next fly fishing goal will simply be to catch a larger Driftless brown trout and to enjoy every moment in pursuit of it. I will fish as often as possible when weather and stream conditions are favorable especially during the spring and fall, fish the better Driftless streams that can support large fish, continue to improve my angling skills, and hope to have good luck on my side.

Diane and I packed up the truck, said and hugged our goodbyes with Steve and Lisa. Once we were back on the road and without the excitement of fishing, camping, and friends, my mind wandered back to my dad and his terminal liver cancer diagnosis: the man who taught me to fish, starting me on a fishing life that is now an obsession for catching trout with flies. An obsession that leads me to sanctuary, solitude, and great sport in this beautiful, distinctive Driftless Iowa landscape. I called my sister to see how dad was doing. She said he had continued to decline and would be moved from home to the nearby Johnston Hospice facility the next day, Monday. As we continued the drive towards home, I thought about the amazingly unique, limestone dominated landscape that is the Driftless, the great time we had with our old friends, the battle I was lucky to win with that great brown trout, and how I value this wonderful cold-water fishery and the serenity and solace I find there. But mostly, I thought about my dad.

My father, Gene Goode Burt, would pass away peacefully on Friday October 15, 2021, with our family and the Johnston, Iowa, Hospice staff by his side. He is missed.

1 Isaiah Bowman, PhD, Forest Physiography: Physiography of the United States and Principles of Soils in Relation to Forestry. (New York and London: John Wiley & Sons, 1911),p. 495.