Periodically, we like to allow one of our Associate Editors to take over the Editor’s column for an issue. We thought Hannah’s extraordinary re-imagining of the prairie’s changing seasonal colors deserved such a recognition. Mark Baechtel, Editor-in-chief

If a fountain could jet bouquets of chrome yellow in dazzling arches of chrysanthemum fireworks, that would be Canada Goldenrod. Each three-foot stem is a geyser of tiny gold daisies, ladylike in miniature, exuberant en masse. Where the soil is damp enough, they stand side by side with their perfect counterpart, New England Asters. Not the pale domesticates of the perennial border, the weak sauce of lavender or sky blue, but full-on royal purple that would make a violet shrink. The daisylike fringe of purple petals surrounds a disc as bright as the sun at high noon, a golden-orange pool, just a tantalizing shade darker than the surrounding goldenrod. Alone, each is a botanical superlative. Together, the visual effect is stunning. Purple and gold, the heraldic colors of the king and queen of the meadow, a regal procession in complementary colors. Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, page 38-39

In this passage from a chapter entitled “Asters and Goldenrod” in Braiding Sweetgrass, one of my favorite books, Robin Wall Kimmerer grapples with the relationship between artistic beauty and scientific understanding of nature. In thinking about Kimmerer’s description of the intertwining of colors of prairie plants, I became interested in the intricacies of color and life present on the prairie. Many view the prairie region of the United States as “flyover country,” deeming the region uninteresting, flat, and monotonous. With this project, I aim to illustrate the raw beauty, diversity, and color of prairie flora using a series of abstract landscapes, created with color swatches derived from plants present during a given month.

Photos by Jon Andelson

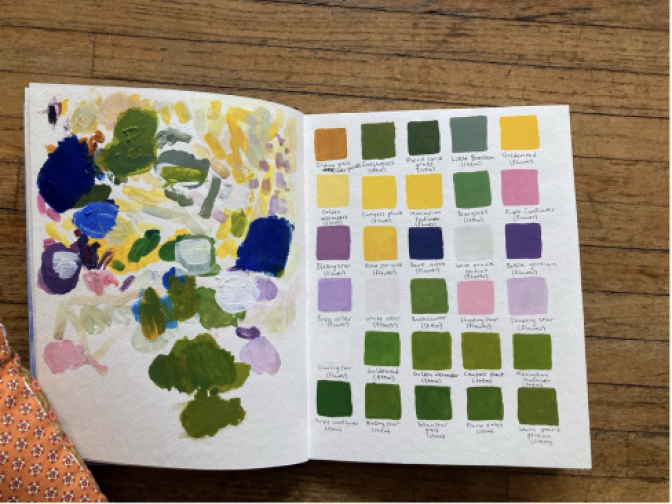

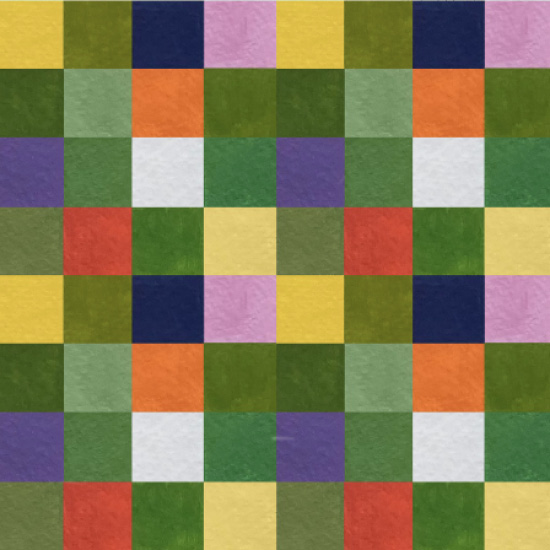

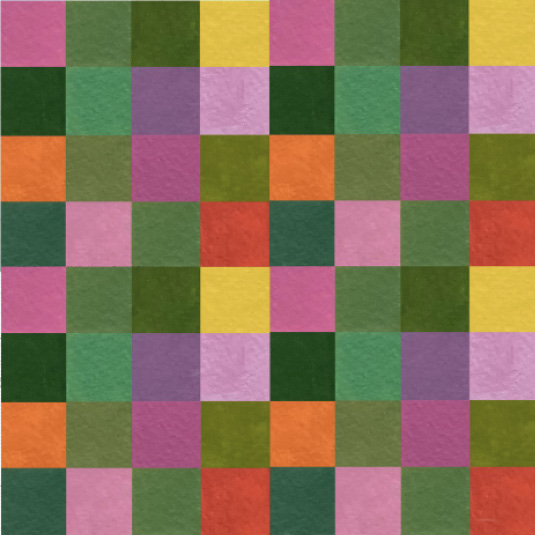

Having grown up in the prairie region, I have seen how plant life on the prairie shifts in color and variety with the rounding of the seasons. To undertake an artistic exploration of those changes, during a time of the year before the colors began to appear, I turned to images of the prairie in a field guide, Wildflowers of the Tallgrass Prairie by Sylvan Runkel and Dean Roosa, and in a short film, “Prairie Through the Seasons,” produced by Grinnell College’s Center for Prairie Studies. I also enlisted the help of avid nature photographer and prairie farmer, Carl Kurtz, who kindly allowed me to interview him about the plants that grow on his prairie in Marshall County, Iowa. I examined individual plant species and swatched the colors of both their stems and seed heads or flowers, mixing acrylic paint and ordering the swatches randomly in a sketchbook. I later photographed my pages of color swatches and cropped colors down into individual squares, arranging them digitally to create compositions representing the colors of the prairie in each month of the growing season. I hope that my “Palette of the Prairie” leads viewers to think about the beauty and variety of life present within the prairie and how that beauty is ever-changing.

The prairie was gray and drab, no beautiful flowers brightened it, it had only dull greenish-gray herbs and grasses, and Mother Earth’s heart was sad because her robe was lacking in beauty and brightness. Then the Holy Earth, our mother, sighed and said: ‘Ah, my robe is not beautiful, it is somber and dull. I wish it might be bright and beautiful with flowers and splendid with color. I have many beautiful, sweet and dainty flowers in my heart. I wish to have them upon my robe. I wish to have upon my robe flowers blue like the clear sky in fair weather. I wish also to have flowers white like the pure snow of winter and like the high white cloudlets of a quiet summer day. I wish also to have brilliant yellow flowers like the splendor of the sun at noon of a summer day. And I wish to have delicate pink flowers like the color of the dawn light of a joyous day in springtime. I would also have flowers red like the clouds at evening when the sun is going down below the western edge of the world.

Melvin R. Gilmore, Prairie Smoke, page 201

May

June

July

August

September

Our language does not distinguish green from green. It is one of the ways in which we have declared ourselves apart from nature. In nature, there is nothing so impoverished of distinction as simply the color green. There are greens as there are grains of sand, an infinitude of shades and gradations of shades, of intensities and brilliancies. Even one green is not the same green. There is the green of dawn, of high noon, of dusk. There is the green of young life, of maturity, of old age. There is the green of new rain and of long drought. There is the green of vigor, the green of sickness, the green of death. One could devote one’s life to a study of the distinctions in the color green and not yet have learned all there is to know. There is a language in it, a poetry, a music. We have not stopped long enough to hear it.

Paul Gruchow, Journal of a Prairie Year, page 80