I’m French and American. I’ve lived most of my life in France, but when my 24-year-old son decided to come to live in the U.S., I asked him if he’d like me to come with him. To my surprise, he said yes, and settling here became our project.

At first, we looked for a room and jobs in a big city, but that all sounded weird to us. In France, we had already had a life different from the majority of people: my son was homeschooled using “unschooling” ideologies, which is very rare in France, and was raised in a non-violent environment without a system of reward and punishment. My priority was to enable him, his brother, and sisters to come as close as possible to being the persons they really are. I wanted to give them the chance to develop at their own pace, the way that suited them. From the beginning, I saw myself as a guide who was learning with her children, rather than being a teaching mother who knew everything, especially what was best for her offspring. As the years passed, my relationship with my four children evolved into something that was closer to a trustful and deep friendship. We had chosen an alternative, ecological lifestyle involving DIY projects, bartering instead of money, environmental permaculture, recycling, and up-cycling.

As my son and I researched our move to the U.S., I asked friends for their ideas and advice. One evening, a friend asked: “Why don’t you go live in an intentional community?”

I had heard about intentional communities in France, but it had always been someone else’s dream. Being a quiet introvert, I couldn’t really imagine myself living with lots of people for a long time. My son and I wanted to explore all the possibilities, though, and researched egalitarian and income-sharing communities. We discovered that our family had been functioning similar to the way that a small intentional community functions, so we thought that a more formal communal living arrangement might be a good idea after all. My son ended up choosing the East Wind Community, located on just over 1,000 acres near the town of Tecumseh in southern Missouri.

East Wind was founded on May 1st, 1974 with some ideals such as freedom and equality. Its founding principles of freedom and equality are probably for me the main reason I’m living here. Residents (65-plus people) are required to do a fair share of the community’s work—at least 35 hours a week. There is a general “no boss” attitude, although there are managers, meaning people responsible for the different areas of the community, and the motto “don’t tell me what to do” expresses another aspect of this ethos of individual freedom. This type if freedom doesn’t suit everybody, but it is attractive to some people.

We arrived at East Wind about one and a half years ago. As we were new people, members were a mixture of suspicious and curious about us and our beliefs, and the fact that we are French made us even bigger curiosities. However, we found a connection with another French American here, who was happy to be able to talk French with us. It’s really when you are away from your country that suddenly the differences show up; it was funny for us to realize how French we were.

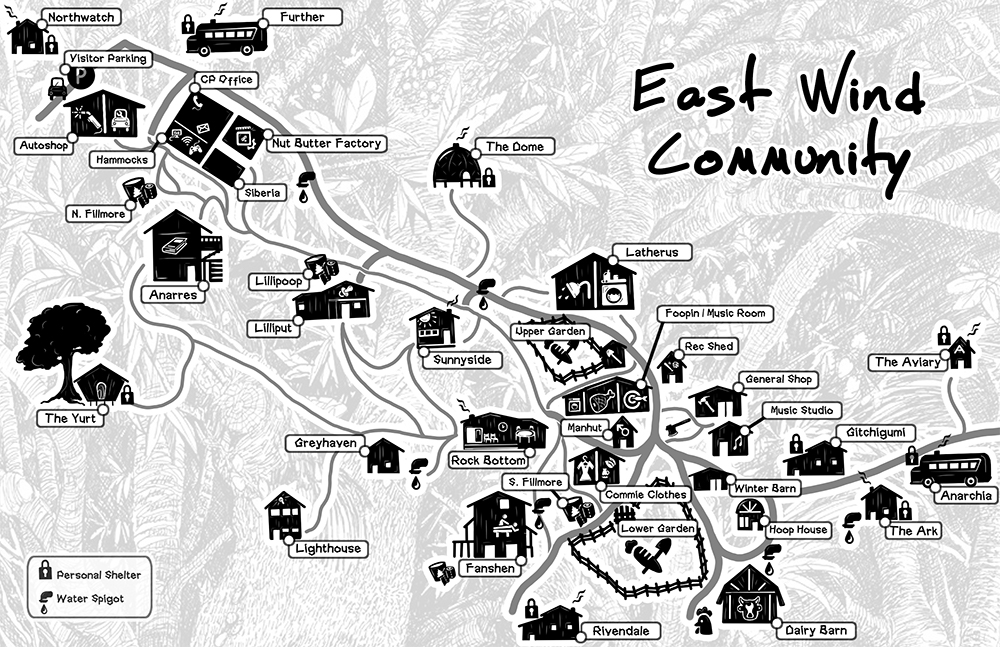

The East Wind Community is located in the foothills of the Missouri Ozarks. Map courtesy of the East Wind Community

After our arrival, for a period of about two weeks, we were considered “guests of the community.” After this we began a “visitor period.” This was a three-week trial, after which—because there weren’t enough concerns raised about to bar us—we became “provisional members” (PM). The PM period lasts for one year after which we were submitted to a yes/no vote to establish whether we could stay on as full members. We passed the vote with success.

Living in an intentional community is different for each person, and as we settled in, I tried to avoid having any expectation for what our experience would be. I thought that my 20 years of experience with various forms of benevolent sharing—with people in many different contexts—would be helpful. I assumed, however, that I would be living in a group of people who shared similar goals, or at least some similar ideals. In the end, all of these assumptions got swiped away, and not always in ways that were easy for me to understand or accept. Living at East Wind might look chaotic to some, but it is rich and complex for others. I’d like to emphasize that my observations are not meant to be judgements. What follows is my personal attempt to bring order to my ideas.

Community defined

According to Miriam Webster’s online dictionary, one definition of a community is “people with common interests living in a particular area.” I had previously thought that a “community” could only be a kind of homogeneous group. While it is certainly true that East Winders are living in a common place, our goals and interests are not at all the same.

I have given lots of thought to the question of this toleration of difference, and the answer is rather complex. In a nutshell, East Wind is a place where people who do not fit in mainstream society can live. It’s a magic island, but it is far from easy to fit in and stay there, in part because its acceptance of difference also makes it a place of constant contradiction and even occasional incoherence.

This should not be understood only as negative, because the contradictory and incoherent aspects of life at East Wind also means openness to enormous possibilities. The energies released in the community are very strong and dynamic, which is not bearable for everybody and explains why there’s so much member turnover. High turnover also partly explains why full members do not generally involve themselves in more than superficial relationships with newly arrived people, or share competencies with them—often saying, as I’ve heard them say many times, that “it’s not worth it.” I know that, for myself, as the months passed, I began to really feel that I was gaining more credibility and was surprised when people suddenly began acknowledging me with a friendly “Hey!” and sometimes engaged in short personal discussions that showed me they trusted me more.

East Wind’s residents in May of 2016. Photo courtesy of the East Wind Community

Products for which the East Wind Community is renowned include nut butter and its line of Utopian rope sandals, produced by its members in the on-site workshop

East Wind bakes fresh bread every day, Agnes is one of seven community members who work at this important task

According to East Wind’s blog, the community ‘assumes responsibility for the needs of its members, from food and shelter to medical care and entertainment. Everyone is free to have their own personal possessions such as clothing, media, and electronic devices. Provisional and full members receive an equal ‘Discretionary Fund’ each month…that members are free to spend as they please’

Personally, I like to meet new people and, in judging the experience, I focus on the meeting in and of itself and not on its duration. One young Italian woman spent less than a week at East Wind—a visit during which she made fresh pastas like her grandma used to. She organized a workshop to teach this skill to the community, but I ended being the only one really interested, so she showed me. After that, I made some of these pastas for the whole community and was able to show others how to make them.

On my side, I was able to teach our Italian visitor and her companion how to make fresh butter out of cream. It was a wonderful and joyful exchange and we’ve kept in contact through email, maybe not on a regular basis, but I know that we could meet each other in some years and the link would still exist. The same with a guy from Morocco who lives presently in Japan, with a couple from Norway who are specialists in Permaculture, with a young woman from China, and with many other American people who visited for a more or less long period. All of these people are now part of a relational web which is very valuable to me, because with each of them I had a very specific, special, unique and deep exchange, not at all superficial though often short.

As I learned, after arriving at East Wind, following the more-or-less polite welcome my son and I received from most of the members, we had to find our way in. People might help or not, and often it’s been a lonely path. It felt incredible, though, to be able right away to enjoy the home-cooked food, and to use the materials and tools, the common computers and library, the many facilities and buildings, the clothing, etc. There is an idea about community items that since they are the community’s, they are not “mine”; but since they are the community’s, “I” can use them. As a result, the materials were not always in such a great shape because of the many (and, oftentimes, quite rough or incorrect) uses to which they had been put. But the possibilities seemed endless.

This freedom-of-action has its downside, though. Often one must protect one’s projects, at least by labeling them (something new people must learn very fast), as some others might just take the tool, space or whatever else one is using. It is then very frustrating to come back to a project and see it has disappeared or was modified. On the other hand, one can see unfinished projects that have been left lying around, some of them for probably many years, and often from members who are now long gone. It gives one a sense of the true dimensions of East Wind’s 45 years of existence.

I thrive on being able to decide when, what, where, and how I will achieve what I want to do. This freedom in organization is for me a real luxury that I did already have in France and that I was so happy to be able to find again in the U.S.

Some members maintain a defined schedule, with fixed hours and a clear distinction between work and leisure, week, and weekend. Others have a more flexible schedule, often changing depending on the weather or just their desire. I personally have about 17 fixed hours and the rest moves around. I love being able to wake up late in the morning not really knowing what I will do with my day, and as I like the quiet, I’m often working at night where I can have the common spaces all to myself, with the only noises being those I’m making.

But there’s more to freedom than doing whatever one wants, whenever one wants to, and as a French saying from the Revolution says: “One person’s freedom ends where another’s begins.” In a group of close to 70 people living together, it’s not easy to know where those limits are, especially without much direct and frank communication, so the overlap is not usually easy to manage.

People are treated as individuals at East Wind, but there are still some commonly accepted rules which evolved over the time. There are bylaws and a set of legislation and policy tools (called “legispol” by the community), as well as unwritten social rules which change depending on the current members. This can render of East Wind’s cultural landscape somewhat unclear. For example, actions like physical violence or trespassing in private space are not tolerated. All in all, to me it feels like swimming in a big body of water, with waves and currents that need to be navigated. Each person has to decide whether to go with or against the waves, and this makes it either more or less difficult.

Socializing revolves mostly around drinking and smoking, but the many parties and events the community holds regularly are open. Although I am a non-drinker and non-smoker, I have always been welcome at these gatherings, at first with some surprised looks from members who were mostly younger than me, but now often with a welcoming cheer as I’m always arriving late to parties that have already started hours before.

I’m not sure whether it’s a cultural difference or a personal need, but it is difficult for me to have a deep and trustful exchange with people here. I very rarely feel the occasion to have an interesting conversation or project with the sharing of thoughts and experiences in a commonly open and curious mindset. This is something that surprised me and that I really miss, as I had many of this kind of valuable exchanges in France.

Ages made the cakes of butter above using cream from the Community’s cows

At East Wind, each of us has a personal room. It’s part of the condition to be considered as a member. The rooms are rather small because of a lack of money when East Wind began, but also because it was originally hoped that the main spaces would be where people mostly spent their time. Meals, gatherings, meetings, and parties are mostly communal, but on most evenings, the majority of community members spend their free time in their rooms. And as I like silence and calm, I must say that it’s quite fine for me that people are not much in those common spaces at night! Personally, I like bigger spaces and not being in a locked environment, so I mainly use my room for sleeping and to store my personal belongings.

Over the past year, I’ve managed to do at least one new and more-or-less-big thing every single day! I’ve learned how to make cheeses and butter with a very skilled member, learned how to bake Parisian baguettes from YouTube, as well as making some beer and wine with different members. It’s ironic that I—a French person—would be acquiring these skills in the U.S.

I’ve served on the social committee, and regularly worked in areas such as the herb garden, childcare, cooking, food processing, wood and metal shop maintenance, and computer installation. I’ve designed a logo, made sandals, and have worked on various other tasks in support of the community, such as doing some monitoring in the nut butter factory, doing secretarial tasks, and packaging some orders. Once a week I drive to town, do errands for the community and drive other community members to various places. Several months back, I was made East Wind Craft’s manager, in charge of the E-commerce platform and the retail section for small businesses.

Because I simply don’t make a separation between life and work, my days are pleasantly quite full. I’m often shifting my mindset and I feel that I’m working, learning and playing all the time. I really enjoy trying to bring something to others, whether that’s by being a direct support or just by making a homemade beverage. Such latitude is a luxury, and I’m happy to be able to have such freedom-of-choice and lifestyle.

I have also found that many of East Wind’s residents are recovering from major traumas. This aspect is very present and heavy in the community. It probably goes a long way toward explaining the attitudes of, and relationships between, members. I deeply believe that because people come here with baggage, they should allow themselves or just be allowed by others to drop that baggage at the community’s entrance and become a part of another society. There are different ways the community helps its people to heal: discussion groups, a talk circle, and a new group on trauma.

But while East Wind is definitely a place where one can heal from past traumas, it’s also a place where one can slide down. This will depend on the personal choices, motivations and willingness as people are often left to themselves or keep to themselves. Respect for the individual is very much a part of East Wind’s culture, but there is also gossip, which can lead to friction and has resulted in some people having to leave the community. In general, people are left to themselves and permitted to do whatever they want, as long as it doesn’t impact others or the community.

Another important aspect is the constant possibility for each member to directly and openly express themselves in front of the whole community by simply writing a note and pinning it up on the different boards displayed in the main common space so anybody can read them. I value this way of communication, but I also have often felt that one-to-one exchange was lacking. When there are issues between members, some people offer mediation, but this has the limits each of the involved community members gives to it, and this leads to problems not always being solved in a satisfying way for everybody. This means that a sense of frustration and resentment can remain, depending on the individual, and this becomes a part of the energy moving around in the community. Broader issues involving more people or being considered as a community issue (such as acts of physical violence, violation of boundaries or of private space) are brought to either the Social Committee, the board, and often to a community meeting which all members can attend. Finance, legislation, and all kinds of projects that involve the community also lead to community meetings with a vote.

Living at East Wind is a special adventure for me. I would never have thought I would be engaging in this kind of lifestyle experiment. It has been an exceptional journey, and though I won’t say it’s always been an easy one, from the beginning I have like felt at home… plus 65 people, all making a big difference!

*To find out more about the East Wind Community, in addition to visiting its website, you can view the videos in the collection posted on its YouTube channel, or read entries in its blog. *

The Light House, where East Wind houses its visitors