“I must hide my memory in a mustard grain

so that he’ll search for it over time until time is gone.

I must lose myself in the world’s regard and disparagement.

I must remain this person and be no trouble.

None at all, so he’ll forget.

I’ll collect dust, out of reach,

a single dish from a set, a flower made of felt,

a tablet the wrong shape to choke on.”

Louise Erdrich, “Fooling God”, 1989

Queen Anne’s Lace (Daucus carota)

On Pressed Flowers and Memory

There’s something about pressed flowers that I have always found so beautiful. When you press a flower, you don’t just preserve the blossom, you also preserve the memory. At my home growing up, we used to have a big, red dictionary that we kept on the top shelf of the broom closet. I would pick tiny flowering weeds, tuck them into its pages, and not stumble across them again for years.

When thinking about the prairie, this same kind of elusive permanence comes to mind. Season after season, the same plants bloom. Each season is reminiscent of the last, but no bloom is ever the same as it was. Through fire, freezing temperatures, and pouring rain, these plants regrow again and again. There’s something so beautiful about their resilience, about the way they survive in spite of our efforts to obliterate them.

Though it’s an invasive species in the Midwest, Queen Anne’s lace, or Daucus carota, has always been my favorite flower, and the fact that I usually see it blooming in the gravelly side of the highway makes it even more lovely in my opinion. Flowers are traditionally associated with the feminine, so I thought it would be an interesting to try and align the lives of Indigenous women in the Prairie-Plains region with the traditional wildflowers in the tallgrass prairie. I had hoped that the flowers could serve as a worthy medium through which to communicate their stories. The connections only scratch the surface, though. The patterns that I found over and over again only reaffirmed what I had already known to be true: that the natural world witnesses our lives, the good and the bad, and continues to grow.

In pressing the flowers I selected, I had hoped to preserve and present a visual representation of a woman’s experience. Instead, I pressed a moment in her life. The flowers I carefully dried out over the last two months contained fear, trauma, hope, love and regrowth. This is the memory in the mustard grain. It’s just no longer hidden.

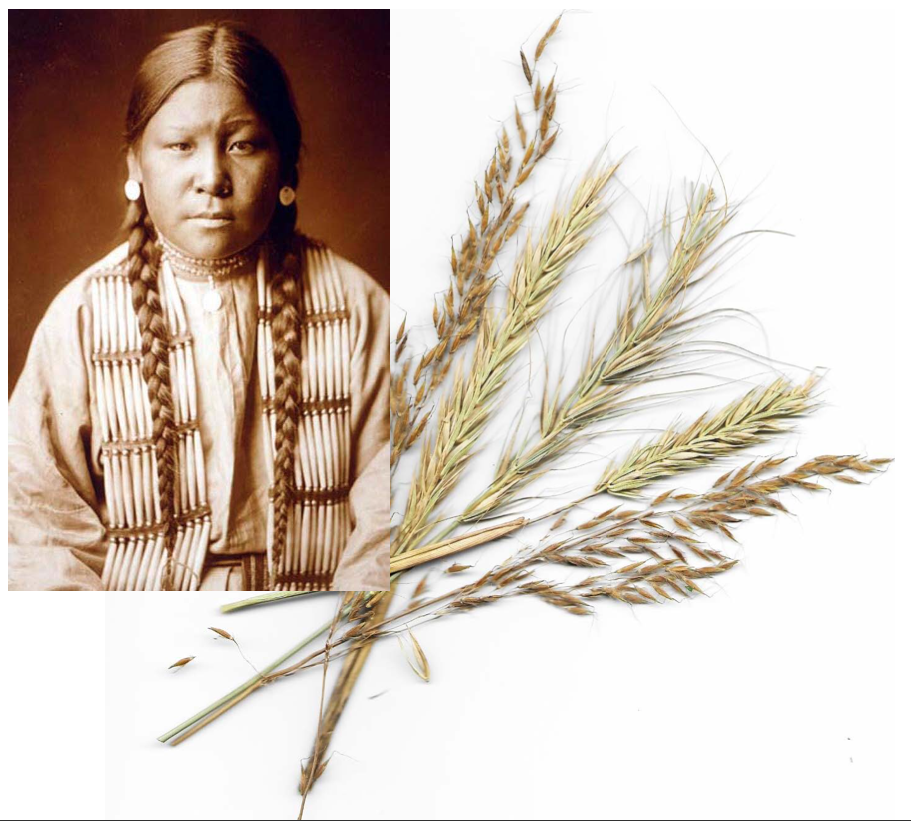

Buffalo Calf Road Woman

When the last days of June tumble into July on the banks of the Little Bighorn River, the only thing that can be seen for miles in each direction is the ocean of grass. Some call them the four horsemen of the tallgrass prairie: little bluestem, big bluestem, indiangrass, and switchgrass.

The Battle of the Rosebud happened on June 17, 1876, in what is now Montana, while these grasses were still getting taller. The battle pitted the allied forces of the Lakota and Cheyenne, led by Crazy Horse, against troops lead by General George Crook. The tribes felt the General and his men were attempting to steal their land from beneath their feet.

During the fight, one of the warriors from the Northern Cheyenne, Chief Comes in Sight, was left wounded on the battlefield. Then the golden sea of grasses parted. Sitting tall on horseback, his sister, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, rode onto the battlefield, picked up her brother with her own two hands, and carried him to safety. Her people rallied, then defeated the troopers.

Since it took place on Rosebud Creek, Crook’s side called it the Battle of the Rosebud. The Cheyenne called it “The Fight Where the Girl Saves Her Brother.”

In ten days, the two sides fought again. We have come to call this the Battle of Little Bighorn or Custer’s Last Stand. The indigenous people called it the Battle of the Greasy Grass. On the shores of the Little Bighorn River, the grass was cold with morning dew. When afternoon came, the sun wasn’t even enough to dry the land. Buffalo Calf Road Woman stood next to her husband during battle. They said she was an excellent markswoman, but she was also quick on her feet and quiet. It was a club, not an arrow, that she used to knock [Lt. Colonel Custer](BROKEN LINK) off his horse. This engagement, in which the people of the plains annihilated Custer’s 7th Cavalry, was only one engagement in the Great Sioux War. After their victory, native forces began to disperse, the army brought reinforcements into the area, and the indigenous peoples were defeated the following May. The victories they won over Crook and Custer all but blew away with the wind. Nearly 150 years later, both sides still tell the story, and Buffalo Calf Road Woman’s brothers and sisters still ride horses through the same grass in her honor.

Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) and Canada Wild Rye (Elymus canadensis). Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Winona LaDuke

Winona means first daughter in the Dakota language, and that’s what she was. Born in August in California, Winona LaDuke would have been far from the Great Plains. She would find her home there, eventually, but by the time she did, the asters and the grass would have been blooming and waiting for over two decades. LaDuke’s parents were an Ojibwe (also known as Anishinaabe or **Chippewa) father and a Jewish mother. She didn’t learn the Ojibwe language until her 20s, after she had graduated from Harvard University.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29668_OBJ.png)

Smooth Aster (Aster laevis). Photo courtesy of Spotted Horse Press

At Harvard, LaDuke learned how to become a voice for the voiceless. Becoming involved with indigenous groups on campus, she embraced her Anishinaabe heritage. After graduation, she moved to the White Earth Reservation, in Minnesota. She taught at the Reservation school and later earned her master’s degree in Community Economic Development from Antioch University. During this time, she helped found the Indigenous Woman’s Network and worked with Women of All Red Nations. Throughout all of this, the flowers of the tallgrass prairie bloomed and faded in their natural cycles.

In 1989, when she was 30 years old, LaDuke founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project. Throughout the 19th and 20th century’s the Ojibwe people had lost nearly all of their 860,000 acres of land. With the European-American model of substance farming on the rise, much of this land had been acquired through improper sales and treaty abrogation. The White Earth Land Recovery Project aims to take back that land, legally. When LaDuke started working, the Objibwe people held only one tenth of their previous land. By 2000, they had bought back an additional 1,200 acres.

But LaDuke wasn’t done. In 1996 and again in 2000, she ran for vice president with Ralph Nader on the Green Party ticket. In 2016, she received an electoral college vote—the first native woman to have done so.

Now she celebrates her August birthday on the prairie. When she looks out her window, it’s likely she can catch glimpses of the blue asters that dot the sandy soil of the White Earth Reservation. The blue aster is one of the hardiest varieties of the aster family. It holds out unusually long and is strong and resilient in response to predators. It grows in sand and on the sides of roads in bursts, and when LaDuke drove to Minnesota after graduating from Harvard, she most likely looked out her window and saw its lavender petals.

Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind

The ox eye sunflower is uncommonly beautiful. Nestled amid golden petals, its center is a sort of sun, beckoning to bees and butterflies. But the ox eye sunflower is also uncommonly strong. Unlike other wildflowers, it can survive in wet and claylike soil. Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, whose Dakota name was Where Thunder Finds Her, was also uncommonly beautiful. And, living just a short walk from the Red River, which divides the plains of North Dakota from the plains of Minnesota, she would’ve walked alongside these wild sunflowers as a girl. When she carried her own daughter for eight months, she would’ve walked these same paths.

She was pregnant when she went missing in North Dakota. In August of 2017, kayakers found her plastic wrapped body floating in the Red River. She was not the first Native woman to be found there. Her family hopes that she can be the last. And alongside the river, despite the horror, ox-eye sunflowers bloomed.

During the subsequent investigation, it was found that on August 19th, a woman had been seen leaving a Fargo apartment with a newborn baby. They were a white couple, Savanna’s neighbors, and they told the police that while the baby was Savanna’s, they didn’t know where she was. The couple later testified that they wanted her baby. They confessed that they had lured Savanna into their apartment and, with a small knife, cut the unborn child from her mother’s womb. Savanna’s neighbors pleaded guilty and were sentenced to life in prison.

Like the ox eye, Savanna was uncommonly beautiful. And she was also strong. Rooting in the clay-like soil that borders wetlands, the ox eye blooms, and begins life again. In late September of 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed Savanna’s Act. In her name, the statute mandates protection for Native girls and women through increased access to data on Native American crime victims and establishment of mandatory protocol and annual reports about crimes committed against Native women. When the House passed Savanna’s Act, the ox-eye sunflower would have just been slowly fading into fall. The U.S. Senate passed the measure on October 10, 2020, as Public Law No: 116-165.

](https://rootstalk.blob.core.windows.net/rootstalk-2020-fall/grinnell_29669_OBJ.png)

False aster (boltonia asteroides) and ox eye sunflower (Heliopsis helianthoides). Photo courtesy of the Bismark Tribune