Mary Swander’s project, Farm to Fork Tales, is a performance piece featuring students from her English as a Second Language (ESL) class at Muscatine Community College. While her students currently live and work in Iowa, their stories capture experiences from all around the world. Upon an initial glance, these stories seem unconnected, separated by geographic location and cultural nuances. Rather than focusing on these differences, Farm to Fork Tales highlights shared experiences between students through farming and traditional food.

Below are excerpts of an interview that our Associate Editor Aru Fatehpuria ‘21 conducted with Mary Swander, as well as four stories from the Farm to Fork Tales performance in February of 2020 at Grinnell College.

Swander: We have some really, really pressing issues in agriculture right now. For example, something like 25 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions are from agriculture currently, but we have the potential to actually sequester that amount of emissions instead of emitting it—to actually pull in the carbon dioxide and sequester it in the soil. And so that’s kind of a hard concept for a lot of people to understand; they don’t want to go there with climate change in the first place, and you know, you can write op-eds and send out memes on social media, but people really don’t get it. Most people just buy their food without much thought of how it was grown, where it was grown, how it’s going to affect their health think that’s a natural place to start: we all eat, we all are involved with food in some way or another, so there’s a lot of consciousness-raising that can be done on just the basic food end of the scale.

[When developing a performance] I look for an artist who can actually illustrate these experiences in some really interesting farmers and artists and get the farmers talking about agricultural issues and get the artists illustrating it them to bring the audience to a more imaginative place and help them full potential of what we could do in the rural environments.

The version of Farm to Fork Tales we performed at Grinnell College was from Community College, where I was hired as an English as a Second Language instructor. I was looking for some new material, and storytellingnow is quite the rage. A lot of people were actually coming to me and saying “Why don’t you do a storytelling project?” and I thought “Well, you know, that’s an interesting idea.” [So now] I’ve done it, and I have this template where I go into a community and get people to tell their own stories about food and farming. So, they sent me into the ESL class, and said “here, have at it!” Each performance needs a theme, it needs a focus, and so what arose from [the Muscatine Community College ESL] group were stories about traditional foods from their own cultures, and some of them a little bit weird for the American ear or palette.

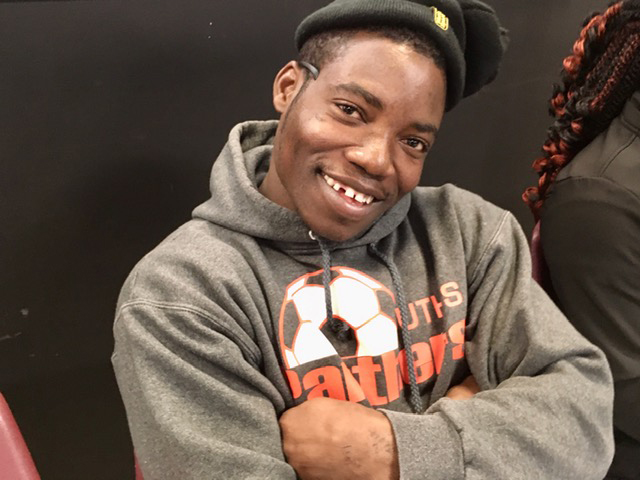

Alexandre (Alex) Tchiladalo Behezi (Togo)

My husband went to a Chinese restaurant. He ate a piece of something—it looked like chicken. He didn’t know. So, he got some, and he ate it. I mean it was good. So after he ate it, he went back to take more pieces. That’s where he saw the sign that says, “Frog legs.”

He didn’t like it because he didn’t mean to eat a frog leg. It was good, though. It was good. But after that whenever he goes to a Chinese restaurant, he always checks and double checks the tag to make sure that he doesn’t eat frog legs anymore.

My mother’s name is Magdaline. She usually went to the market in Togo and bought her favorite meat. One day she went to the market and didn’t see her favorite meat seller. Then she asked her neighbor about the seller. He answered her that it didn’t rain, so there weren’t any earthworms on the farm. She was terrified to know that she was eating giant earthworms all this time.”

Marilisa Trimboli (Brasil)

My daughter tells this story:

“It was my friend’s son’s first birthday party. The grandparents owned a Mexican restaurant, so the food they served was Mexican style. So, when you went to the buffet, they had steak. They had chicken. They had lamb, plus all the sides. They were delicious. So after I ate [the food on] my plate, my husband looked at me and asked me what was my favorite dish. And I said, ‘Oh, I really liked the lamb.’ But everything else was delicious, too.

“So we decided to go for seconds, and when we got there, I put the lamb on my plate. My husband grabbed a few other things. And we ate. It was the end of the birthday party, and we decided to take off. And so we went to say good-bye to the parents, and kid, and once we got to the grandparents, we started talking to them, and I said, ‘The lamb was really good.’

“And Grandma goes, ‘Oh, did you like it? That was Linda.’

“So, to back up the story, the kids’ grandparents are the parents’ next door neighbors. And a few days prior to the birthday party, they shared a picture on Facebook saying that they had gotten the lamb for the one-year-old.

“So, I shared this with my parents and said, ‘Hey, look, that’s your new neighbor.’ And we were laughing and we were wondering what animals we should bring to the backyard to complement and compete with the unusual lamb that the grandparents bought.

“The lamb was called Linda, and they decided to make Linda one of the main dishes. And I couldn’t believe that I had eaten Linda! But Linda was delicious and I went back for seconds!”

Ephraim Sanchez (Mexico)

This is a story from when I was a kid, probably seven to ten years old. My brother was a little older than me. In Mexico we had a farm. We had a lot of fields. So at one time, it rained a whole lot, and my brother and I went to growing beans at that time. We wanted to make sure there of water on there, you know, so we could get it out if we needed to.

But anyway, when we were going to work on the farm, we usually would take lunch. But that day my mother wasn’t able to fix us lunch, so we just went on. We took a pack of tortillas and some hot sauce. That’s it.

So anyway, we went there and we were doing something to get the water away from the field. As we were doing that, we were talking and said, “Well, what are we going to eat today?” You know, my brother and I.

He said, “Well, I don’t know…”

I said, “We’ll just have tortillas and hot sauce.”

We used to take shovels and machetes and all that. Shovels to dig the water out, and machetes to cut down whatever. And then we saw this armadillo coming out of the ditch. It wouldn’t move. He was just there looking at us.

I said, “What do you think?”

My brother said, “Well, why don’t we just go ahead and do it.”

We killed it with the machete. It was because we were really hungry. After you work, of course, you get really hungry. So anyway, we killed it and then we discussed, “How we going to cook it?”

“Well, we don’t have any dishes, or any pots or frying pans or whatever. So why don’t we just get a lot of wood and make a bonfire? And we’ll just throw it on there.”

So we did that. For fifteen to twenty minutes we just kept putting more wood on the fire until we thought it was done. So we got it out. Then we said, “How we going to eat it now? We don’thave any spoons or anything. So it was hard on the top. So we just turned it upside down, and it was soft on the bottom. It looked pretty good. But I was doubting. I said, “Well, I don’t know if I should go ahead and try.”

But my brother said, “Oh, come on. Let’s go so that we can finish what we’re doing and we can go home.”

So we poured the hot sauce on the armadillo. We just mixed everything that was in there. Right in the shell. We got a stick and we just mixed it with the hot sauce. We just grabbed it with our hands and ate it with a tortilla. We made armadillo tacos. It tastes like pork meat. It was really good. We were full and went home. We told my parentsand my mom said, “Yes, you can go ahead and just eat anything out there.” Rather than fixing us lunch.

Carolyn Levine (the United States)

Food so often goes along with a special occasion. Sometimes food marks those occasions, along with other elements.

My husband and I planned to get married. We’d been away from our childhood homes for years, and many of our friends lived all over the country. And, “back in the day,” as my younger friends would say, we didn’t have “destination” weddings. We decided to get married in Chicago, with just our immediate families present—parents, brothers and sisters, and grandparents. And for our honeymoon, we were going to drive back to NYC, which we’d just left, to borrow an apartment in Greenwich Village and hang out with our friends.

But first, we met in Chicago to spend a few days, to be followed by our wedding ceremony.

The night before our wedding, my future father-in-law planned a dinner for our families. His parents had immigrated from Finland. His father, my future husband’s grandfather, had died in his 20s from black lung disease—as an immigrant, he’d worked in the mines in Minnesota. His mother eventually remarried, and he was raised in Massachusetts. His Finnish culture and heritage were a critical part of his identity, and the identity of my future husband and his sisters.

Our dinner, then, not unexpectedly, was at a Scandinavian Restaurant with a dinner theater. This time I was correct—I had not eaten Scandinavian cuisine. The buffet was beautiful and delicious, with many types of fresh fish and Scandinavian dishes.

Following dinner, the theater performance began…with puppets giving the performance. The play was My Fair Lady. We knew the play, but hardly remembered all the songs. But the one song we did catch was “I’m Getting Married in the Morning.”

And when that song began, my future husband and I of course looked at each other and grinned—because we WERE getting married in the morning. And we did!

Swander: There’s identification with traditional foods, even among different countries. From Carolyn’s piece, you begin to see foods are regional and what you thought was religious food —you know, she thought she was eating Jewish food and it really turned out to be Polish food and Russian food, and so if you pull back the lens a little bit, you can see how you’re connected and interconnected to other people through food when you might just think it’s your menu, or other people think their menu is everyone’s menu. And then you realize, “oh hey, I guess not.”

A real camaraderie has developed [among the Muscatine Community College students] and you know, if you’re on tour in the van for a lot of hours as we were, you kind of get to know people’s habits and quirks, and it was a really fun group. Carolyn is not an immigrant; her parents and grandparents were. She was just a community member in Muscatine, and she said, “I don’t even know what happened, I intended to audit this course and just sit in the back and now I’m on stage and I’m touring across the state!” So, you never know what’s going to happen with something like this. [The beauty of performances like Farm to Fork Tales is that] the arts touch this creative place deep inside all of us that not only wants entertainment but wants an emotional release. It can be a release that’s very poignant and moving, it can be very sorrowful, but it can also be a release of humor, playful and fun. And that’s what you don’t get from an op-ed. Not that I don’t like op-eds—I certainly read a lot of them—but the arts bring so much more to an audience.

Photo by Jon Andelson