In response to the pandemic the Iowa Board of Health, like those in the surrounding states, placed the entire state under quarantine. Public gathering places closed, including schools, theaters, and churches. Face masks became part of being dressed appropriately when interacting with others in public spaces, although some, including public officials, resisted wearing them. Businesses slowed down or shuttered. People self-consciously stopped shaking hands. Doctors and nurses felt overwhelmed and often unequipped to deal with the crisis.

The year was 1918. The pandemic was caused by an H1N1 virus and became known as the Spanish Influenza, but not because it had come from Spain. Spain was a neutral country during WWI and, unlike other European countries hit by the disease, had no reason to hide the truth about the flu’s impact. Historians estimate that the virus infected about one-third of the world’s population. At least ten percent of those infected died. World-wide 50 million people or more succumbed to the virus or to secondary infections. In the U.S., the death toll was about 675,000 people. In Iowa, according to Professor Steffan Schmidt of Iowa State University, an estimated 93,000 people were infected and over 6,000 died.

Our current experience with the novel corona-virus (COVID-19), 102 years later, shows disquieting parallels. Because there was/is no medical “cure” for the viruses, our responses then and now are not that different: travel restrictions, educational campaigns, ban-ning of gatherings, social distancing, face masks, plenty of hand-washing, traceing contacts, and hospitalization with oxygen remain the main techniques. Both in 1918 and 2020 some people advocated treatments that were at best untested and at worst harmful. Now as then, states and cities varied in their response to the virus. In 1918, the city of Philadelphia did not implement a timely quarantine, its health director believing the virus was simply normal flu. Instead, the city waited until after an annual celebration had passed. The city of St. Louis did implement a timely quarantine, and the mortality rate in St. Louis was one-eighth that of Philadelphia. As the city went, so went the state. Pennsylvania had the highest mortality rate in the country—880 per 100,000. Nearly 0.9 percent of the population died.

In 2020, Iowa has been one of a handful of states that did not require a shelter-in-place response to the pandemic. As Rootstalk goes to press, Iowa has recorded 27,197 infected and 695 fatalities. Needless to say, these numbers are not final. Indeed, it is impossible to know at this point when the final number will be reached. The Spanish Influenza pandemic is often considered to have lasted about fifteen months. Today, experts are widely predicting a resurgence of the disease in the autumn of 2020. In 1918, when restrictions on social gatherings were lifted, often 2-8 weeks after they were enacted, the virus flared up again.

Another parallel between the pandemics of 1918 and 2020 can be found in their devastating impact on the economy. We are only at the beginning of this impact today. Of particular interest in Iowa and the prairie region are the connections between pandemics and our system of food and agriculture. In 1918, labor shortages caused by the Spanish Flu resulted in some crops not getting harvested. This seems unlikely today due to the highly mechanized nature of Midwest agriculture, but a counterpart is the high rate of COVID-19 infection in meat-packing plants in the region and the consequent disruptions to the supply chain. The proximity of the workers is one of the causes. The ethnic makeup of those workers explains one of the consequences: a disproportionately high infection rate among Latinos. In Iowa, for example, where Latinos constitute six per-cent of the population but a much higher percentage of meat-packing plant workers, they are experiencing 23 percent of the diagnosed cases. Other factors predisposing this population to higher rates of morbidity are poor diet, a history of hypertension, and impaired access to medical resources due to low income and a lack of secure membership in their communities.

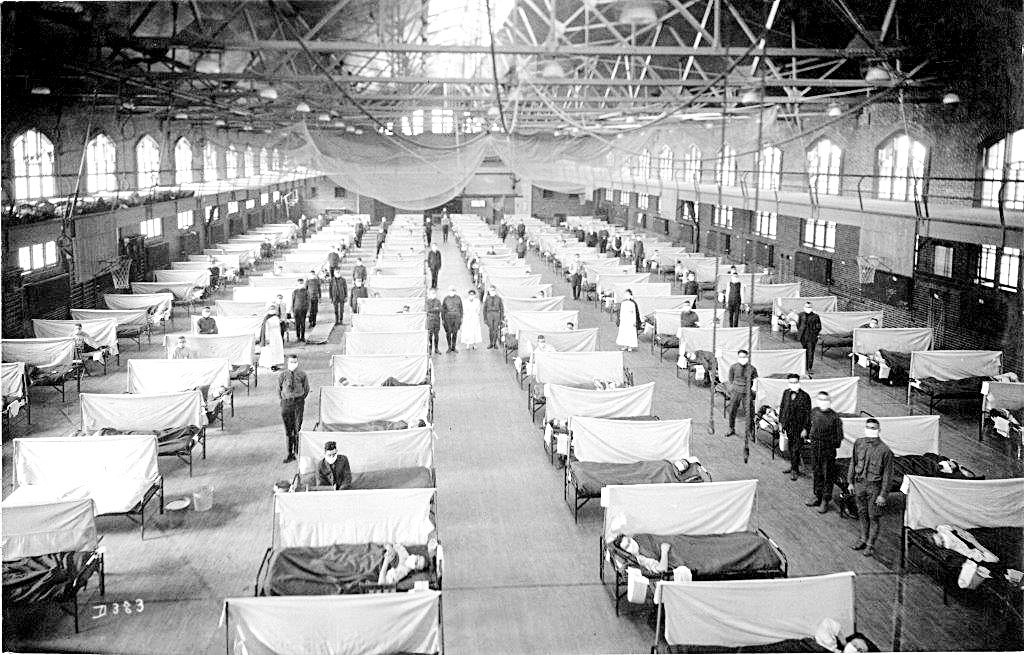

In 1918, the Iowa State University Fieldhouse was converted into a hospital for victims of the Spanish Flu. Photo courtesy of the State of Iowa Historical Society adn the Annals of Iowa

Katie Brandt (lower right corner, wearing headband), performing at the Iowa State Marching Band Festival in high school. Photo courtesy of Bridget Brandt

Farmers today are facing bottlenecks in food supply chains, preventing them from getting meat, milk, and crops to market. This has led, in various parts of the country, to farmers dumping excess milk, burying excess onions, and euthanizing excess hogs — a painfully ironic tragedy when millions of people face food shortages due to limited supplies or unemployment related to the coronavirus. According to a recent CNBC News analysis, meat shortages are likely to last through the pandemic. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the structure of our industrialized food system lies at the heart of these problems. Would the impact of the coronavirus have been different if we had a more localized food system, with shorter supply chains and less centralized and concentrated production processes?

That is one of many questions the pandemic demands we address. Right now, we are in the midst of coping with it. When it subsides, the nation and the world will have an opportunity to rethink how we deliver health care, how we raise food, how we distribute wealth, how we govern ourselves, and how different governments and different levels of government should coordinate with each other. The choices we make will affect not only the severity of the next pandemic (which most experts think will not wait another century to strike us) and how we respond to it, but also the kind of society in which we live. Beyond even that, the choices will indicate our character as a nation. And at the deepest level, the choices the world makes will reveal much about human nature.