“That’s a fucking beaver in the middle of the road!”

Sofia shrieked from inside the maroon SUV, then burst out laughing. The rest of us turned to get a look before the traffic light turned green.

It was as if we’d found a living talisman for the weekend, focusing our attention like a bullseye smack dab in the center of Rock Island, Illinois. The beaver was unexpected and out of place, as incongruous as the monumental painting that we’d driven 300 miles to see had seemed in Davenport, Iowa, just over the river. And yet here we all were: me, my friends, the painting, and now a three-foot long beaver, sitting on its haunches amid the rundown wooden houses and boarded up storefronts in the center of a town apparently more dismal even than Davenport, the city across the Mississippi that we had already christened, “Where Hope Goes to Die.”

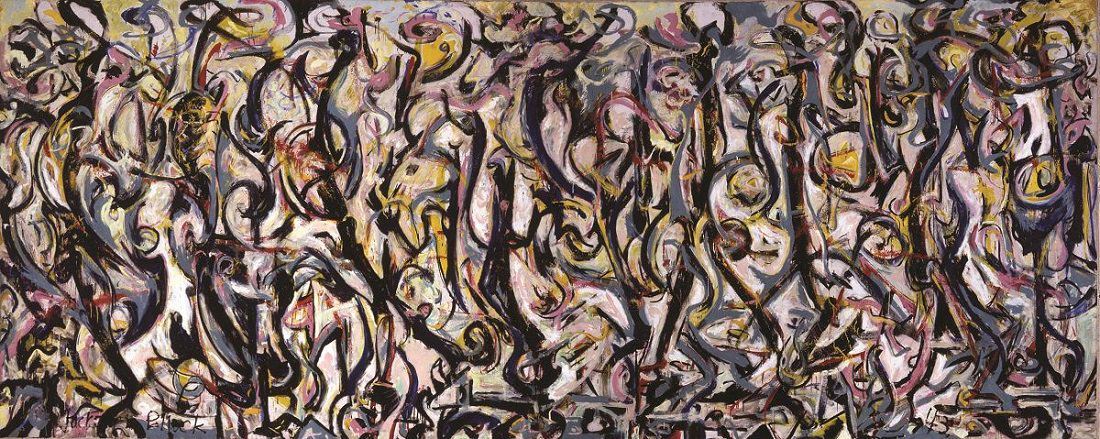

We had come to Davenport to see Jackson Pollock’s Mural, one of the most important paintings in the history of modern art. It launched Pollock’s career in 1943, established Abstract Expressionism as the major art movement of the 20th century, and solidified New York City’s emergence as the center of the international art world. It was commissioned specifically to fill, and according to some accounts even trimmed to fit, the entryway of heiress and art patron Peggy Guggenheim’s Upper East Side brownstone. It was a product of the city in which it was created and a catalyst that helped create what that city would become.

Mural belonged in New York. An east coast transplant myself, I couldn’t help feeling a bit sorry for the painting; I felt surprised and almost embarrassed that it had not found a worthier home. Mural deserved a showcase on a major stage; instead it ended up in Iowa, just across the river from a neighborhood whose greatest attraction appeared to be a beaver in the middle of the road.

To give credit where it’s due, Davenport’s Figge Art Museum is lovely. When we were there, its galleries were so empty that I managed to flout the rules and get a photo of myself standing next to Pollock’s masterwork. I was not unfortunately, quick enough to find my phone and snap a picture of the beaver, even though Danielle was driving slowly as she maneuvered her enormous Ford Explorer through the Rock Island crossroads that hot Saturday afternoon. We had crossed the river after our museum visit to see what else there was to do in the Quad Cities, and like the listless citizens of Rock Island who were slumping about the downtown intersection, we had not found much. Just a beaver in the middle of the road, hands to its mouth, snacking on something that none of us in the SUV had any desire to contemplate.

“Did it just crawl up from the river?” Kristina asked rhetorically.

“I don’t think it’s a fucking pet,” Sofia replied.

* * *

In addition to Rock Island and Davenport, the Quad Cities include Moline, Illinois, and Bettendorf, Iowa. We didn’t visit all four, but I feel confident saying that Davenport is queen of the Quads. Its population is over 100,000. Its downtown features several buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. Jazz musician Bix Beiderbecke was born in Davenport, as were several professional athletes whose names are unfamiliar to me. Davenport is headquarters for an upscale regional department store chain; it is served by four interstate highways; and in 2015 it had 168 confirmed shootings, at least according to Wikipedia. For a city of 100,000 that seems like a lot, but of course that number refers to shootings, not homicides.

No place is perfect. It would be churlish to run Davenport down or suggest it doesn’t deserve to house a masterpiece of modern art. I certainly don’t mean to suggest that people in the Midwest can’t appreciate the avant-garde or that the painting is wasted out here in the hinterlands, hundreds of miles from a major airport or population center. Well, maybe I do mean that last thing, at least a little. Because Davenport felt like nowhere, and this was a surprising conclusion to draw, especially after visiting with this group of friends. We generally found the charm wherever we went.

We had met a few years earlier as tour guide trainees at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center. We were an unlikely clique, ranging from 32 to 62 in age, our music preferences running from punk metal to opera. All but me had grown up in Minnesota, but our backgrounds ranged from Panama to Latvia to one-quarter Chinese. Each of us was probably an odd duck in her own way. But during a year of studying pop art and conceptualism and visual theory, we had clicked like crazy. No one thought it strange when I suggested we travel 300 miles just to see a painting.

We had traveled together before. The previous summer, for example, we had taken a road trip through Pennsylvania. Between the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia, there were many highlights, like the night we met Kiefer Sutherland (who was then starring in the Fox TV series 24) at a bar in downtown Philly and Kristina asked him to take a picture of us. Which he did, quite graciously.

But my favorite was the night we’d spent in Hershey. We were all checked in to our motel when Danielle and Kristina decided to go to a biker bar they’d seen down the road. Danielle had grown up around motorcycles, and biker bars were kind of her milieu; plus she and Kristina were still flying high from all the M&M samples they’d scarfed down on the chocolate factory tour.

It was midnight, Sofia and Nancy had already gone to bed, and I was in pajamas: black crop pants printed with multi-colored teapots and a solid black tank top. But I had never been to a biker bar. Kristina convinced me I didn’t need to change, and she was right, although I did take 30 seconds to put on a bra. At 52, I was the second oldest in our group and felt some obligation to keep things classy.

The band was loud, and the bar was outstanding. I did my first-ever Jello shots (green). I admired the bountiful tattoos gracing the arms, chests and necks of the bar’s raucous patrons. I noted with pleasure that even in my teapot pajamas I was one of the best dressed women in the room. The only real contender was a tall, thin woman in a bejeweled, flesh-tone unitard who was swaying to the music at one side of the dance floor, a sinuous, writhing cylinder of bleach blond hair, beige skin, beige spandex, and, I suspect, imitation gold.

At some point a skinny old guy staggered up to the open area where the band was playing, fumbled the microphone from the lead singer and began garbling a tribute to his fiancée. Turns out we had crashed an engagement party. The bride-to-be clambered past a few tables and stumbled up to stand next to her intended.

She was no ingénue, but then again neither was he. They appeared somewhere in age between 40 and 70, and they looked a lot alike: blotchy and pale, dressed in metal band t-shirts and torn jeans, squinting and unsteady under the harsh stage lights. They both had shoulder length hair of indeterminate greyish color. I couldn’t keep myself from contemplating how much conditioner it would take and how many combs would snap in two if either one decided to detangle before the wedding. They wobbled together as he sang, his voice raspy and his words unintelligible. They were beyond drunk, they were grinning a mile wide, and they were god’s-truth adorable. I don’t think they had a full set of teeth between the two of them.

All of which is to say that when I travel with this group of friends, we do not seek out high-end experiences. We did not go to Davenport expecting pâté and pinot noir. We really had no expectations, except for the Jackson Pollock painting.

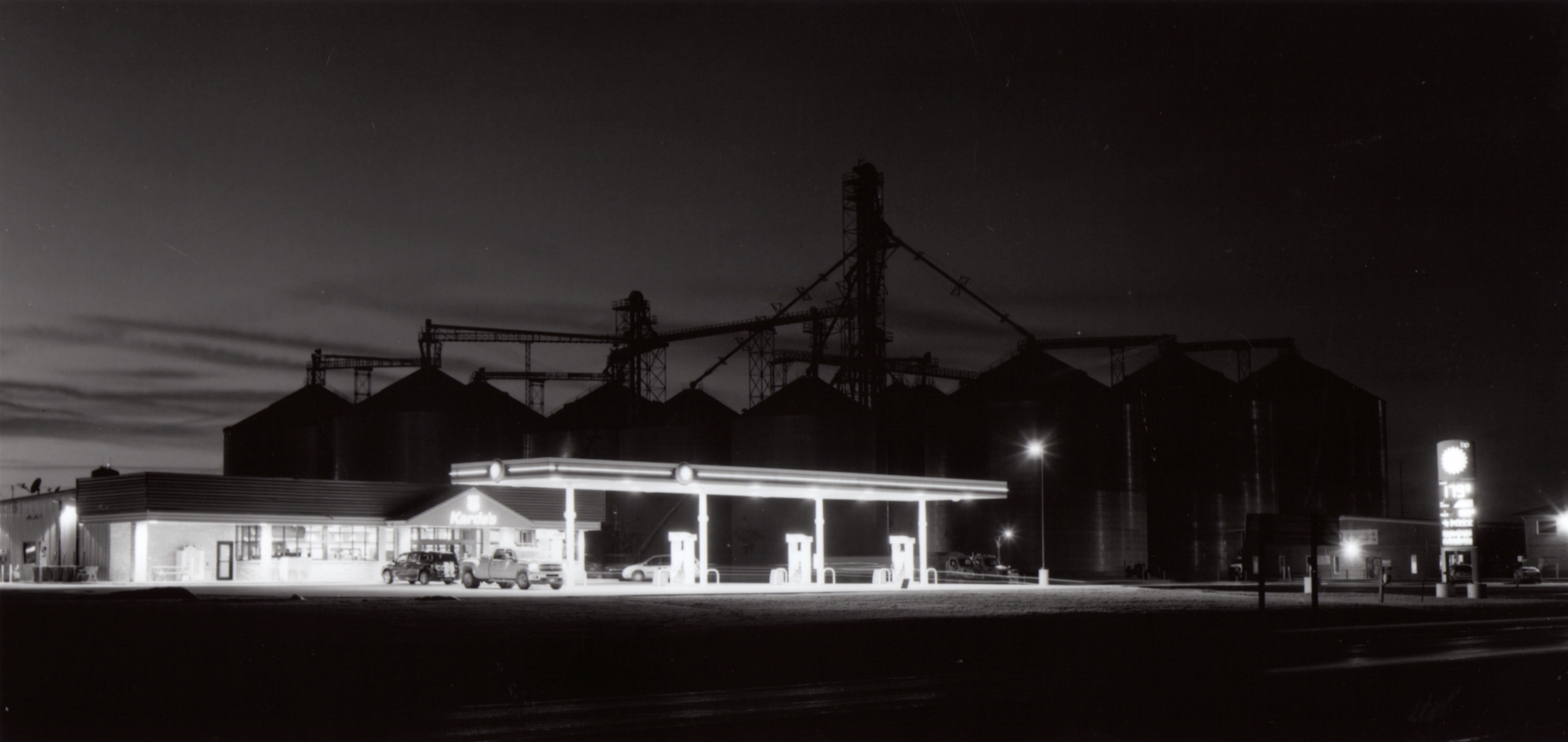

“Grain Bins and Gasahol,” by Robert Fox. Silver-gelatin print, 2016

* * *

We arrived in Davenport on a Friday night and checked into a large, clean motel just off the interstate. We did not look like any kind of family or professional grouping, so maybe the nice young man at the motel desk was just confused when we asked what there was to do downtown. The museum, we knew, was closed at that hour, but there had to be some restaurants open on a Friday evening. Maybe a movie theater, or even a concert in a park?

“I don’t know. I never go there,” he said. That seemed odd. We weren’t too surprised he hadn’t been to the art museum, but downtown was just down the road. If he never went there, where did he go?

Still, downtown seemed like a better choice than the strip malls by the highway. By the time we got there it was about 9 p.m., the sun was setting, the night was warm. There were a couple of main streets lined with brick and sandstone buildings, tall enough to feel like they were closing in on us as the sky grew dark. A few bars had their doors open and we could hear their music playing.

There did not seem to be anything else—no restaurants, no theaters—just indifferently shaven young men, mostly blond and wearing loose-fitting jeans, clustered in the bars’ open doorways, drinking, bobbing lightly to the music, some juggling cigarettes in the same hand that grasped the necks of their beer bottles. We passed a hot dog cart on a corner. Emphatic guitar riffs and the thumping of overloud bass filled the air with noise, suggesting a party atmosphere, but the streets were dark and foreboding, despite the music. The bars seemed barely lit, and there were not many lights on inside any of the buildings around us. We approached one of the groups of young men. They were not rude when we asked if there was anywhere open to eat.

“I think there’s a hot dog cart down the block,” one of them suggested helpfully.

There were young ladies on the scene, too. They seemed more interested in walking from venue to venue, a Midwestern version of the Italian passeggiata, perhaps. They had dressed up for the evening stroll, far more so than the men. Fitted jeans with metallic embroidery on the back pockets; thin, gauzy tops. Dangly earrings. Eyeshadow. Mascara. Long hair that had been bleached, or moussed or styled with a curling iron, or maybe some combination of all three. Most were pretty. All of them wore high, spiky heels and tottered on the uneven pavement as they walked in groups of three or four. They were probably in their early 20s, the same age as the more casually groomed men. This was it, their prime, the glory days they would look back on.

I wondered how much time it had taken the young women to get ready for their evening out, how much their feet hurt in their three-inch heels, how much hope they’d invested in what the nighttime streets of Davenport had to offer. I hoped the guys playing pool and air guitar were worth it.

* * *

An advantage of seeing Mural at the Figge was that we had it to ourselves. The painting is enormous, approximately eight feet high and twenty feet wide. Before Mural, Pollock had been painting far smaller canvases, tending toward abstraction but still representing recognizable images. Mural was his first large-scale all-over abstraction. Seeing it was amazing. I stood close enough to see the uneven texture of the paint that Pollock had brushed, spilled and thrown onto the canvas. I stood back to take in the picture as a whole, to absorb its dense succession of black and teal swirls, arrayed vertically across the wide expanse of the horizontal picture plane and shadowed with splotches and echoes of yellow, mauve, red and white. The effect is overwhelming: nonstop motion, force and energy, somehow contained in two dimensions. Some people see shapes or ghost-like figures in the lines and colors. Pollock reportedly used the word “stampede” to describe the vision that inspired the painting.

It’s not just the painting itself that is fantastic; it is the story of its creation. In 1943 Pollock was an emerging artist, struggling to make a name and a living for himself in New York, the city where new and established artists had come to congregate, Europe*—and particularly Paris—*having been overrun by the Nazis. Pollock was included that year in the Spring Salon for Young Artists at an exciting new gallery called “Art of This Century.” The gallery was owned and run by Peggy Guggenheim, one of New York’s most important collectors and a major promoter of contemporary art.

Shortly after the spring salon Guggenheim commissioned Pollock to create a large work to fill the hallway of her new brownstone at 155 E. 61st St. New York was usurping Paris as the art world’s epicenter, and Guggenheim wanted to proclaim her support for new American art and artists. The commission would augment her status as a taste-maker and patron, and would give Pollock an opportunity to develop the potential Guggenheim and her advisers saw in his smaller scale paintings.

Pollock signed the contract in July 1943. He received a monthly stipend from Guggenheim, unheard of for artists at that time, and was given complete freedom as to what to paint. But instead of painting directly on the wall, Guggenheim wanted Pollock to create an enormous canvas, something ostensibly portable. Pollock had to knock down the wall between his studio and his brother’s next door in order to accommodate the project. He hoped to have the painting done for a show at Guggenheim’s gallery in November.

In a frenetic and heroic burst of energy, Pollock painted the entire canvas in one night just before the deadline.

November came and went. The enormous canvas was untouched. Guggenheim grew anxious about whether the commission would be completed; Pollock grew anxious and depressed about his ability to complete the commission, and about the ramifications if he failed to satisfy one of New York’s most important patrons. More weeks passed. Guggenheim wanted the painting by New Year’s Day 1944 at the latest. Pollock was blocked.

Then, in a frenetic and heroic burst of energy, Pollock painted the entire canvas in one night just before the deadline. As soon as it was dry he brought the rolled up canvas to Guggenheim’s townhouse only to find it was eight inches too long to fit in her hallway. Marcel Duchamp, the émigré artist who a generation earlier had revolutionized art with a notorious sculpture made of an inverted urinal, and now one of Guggenheim’s closest friends and advisers, solved the problem by cutting eight inches off one end of the canvas. So the story goes. Duchamp’s trim job is unconfirmed.

The painting and Pollock became instant sensations. After seeing Mural installed in Guggenheim’s apartment, New York art critic Clement Greenberg proclaimed Pollock “the greatest painter this country has produced.” Life Magazine would echo the sentiment in a cover story a few years later. Pollock’s career soared; large-scale, all-over “action painting,” as he called his very physical technique of pouring and throwing paint onto enormous canvases, would revolutionize the definition of art.

Decades later art conservators would question whether Mural could really have been painted in one manic all-night session. Pollock’s wildman persona made the story seem credible. Pollock had been born in Wyoming and raised in Arizona and California. Remote, tempestuous, unpredictable, Pollock embodied the myth of the American West in both his personal life and in his art. It made sense that this untamed genius would associate Mural with a stampede, and the story of the painting’s creation lives on as one of the greatest legends in the annals of art history.

Mural’s ultimate fate, however, turned on a bit of practical irony. Although Peggy Guggenheim had commissioned a portable masterpiece, when she decided in 1947 to close the Art of This Century gallery and move she could not bring the painting with her: her new home in Venice did not have enough room. Guggenheim wrote to an art world acquaintance, Lester Longman, head of the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History, and offered him the painting if he could pay for shipping. In October of 1951, Mural arrived in Iowa.

* * *

I am not from the Midwest. I grew up in Boston and always imagined I’d end up in New York, or Washington, DC, or maybe San Francisco; and I did live briefly in all of those places. But I married an academic, and because I was waffling in my own career, we ended up following his job opportunity to Minnesota. I came here voluntarily, went to law school, raised two children. My choices, freely made. It’s not like I was put in a box and shipped.

I’ve lived in the Midwest for more than 30 years, and I’ve pretty much made my peace with it. The Twin Cities, unlike the Quads, are a major metropolitan area, with plenty of theater, good restaurants, and, if not the teeming diversity of New York, at least enough of a population to offer a range of people and experiences. There is a lot to do here, and it’s all more accessible than it would have been in the Northeast or the West Coast. It certainly would have been harder to get accepted as a volunteer tour guide in a bigger city with a more prestigious art museum.

But the thing is, I feel out of place in the Midwest. My slight accent, dark hair, and ethnic features mean people always ask if I’m “from here” or, more specifically, if I’m from New York. The answer to both questions is “no” and requires me to explain continually who I am and why I live in Minnesota. An inordinate number of people seem to have grandparents with farms; my grandparents, both sides, lived in run-down inner-city apartment buildings. Maybe because of their farm backgrounds, people here talk about gardening. A lot. It’s no one’s fault that I glaze over when people talk about their yard projects. It’s no one’s fault that I have nothing to add when people talk about their weekends spent with local relatives or friends they’ve known since grade school. It’s no one’s fault that so often I end up feeling like the oddball, or resentful that I don’t have my own set of nearby relatives or childhood friends, particularly on lonely weekends when everyone else seems busy.

Truth is I’ve always been a hard fit. Not pretty or athletic enough in high school (who is?). Not outdoorsy or vegetarian enough in graduate school (Berkeley). Not young enough to be part of the crowd in law school (here in Minnesota), not old enough or rich enough to blend in at the first museum where I volunteered as a tour guide (the Minneapolis Institute of Art, before I switched to the contemporary art center where I met my gang of friends. Finding my place has always been a struggle, and I can’t blame it all on Minnesota or the Midwest.

But in my worst moments, I do. In my worst moments, I remember that when I was interviewing for jobs after law school, all people did was look at the Boston-Berkeley-DC trajectory on my resume and ask, “What are you doing here?” Apparently if you’re not from Minnesota or the Dakotas, Iowa or Wisconsin, people get suspicious. I don’t imagine anyone asked Jackson Pollock why he moved to New York, but my prospective employers were obsessed with my geographic dislocation. So, instead of talking about my interest in immigration law, we’d talk about my husband’s teaching position and why he and I chose to live in the cities rather than the small town 30 miles south where his college is located. I eventually received several job offers. It turned out I didn’t fit at my law firm either. This was not particularly uncommon for a woman litigator in the late 1980s, but it didn’t help that I started work feeling like an outsider because I was not from the Midwest.

It’s not just my professional life. In my worst moments, all I see is flatness and space. So much space. We envelop ourselves in it, like a bubble wrap of single family houses and wide streets and Midwestern politeness—they call it “Minnesota Nice” here—that protects us from interacting too closely, too rudely, with strangers. But when you come here as a stranger, that bubble wrap ends up feeling less like comforting protection and more like social quarantine.

In my worst moments, I miss the energy of a bigger city, and I ache for the reassuring anonymity of urban life. Being alone in a big city makes me feel powerful. It’s not strange to be alone in a big city, it’s an accomplishment. It means I’ve mastered the streets and subways and buildings and crowds; that I’ve become an insider; that I have, like the thousands of individuals around me, became part of a dynamic whole. When I’m alone in the Midwest, even in Minneapolis, I don’t feel part of anything greater, I just feel alone. Other people say they feel so “at home” here, but they’re at home with their doors closed, and no one has invited me in.

So in my worst moments, all I see is that everyone else’s contentment has made me feel excluded. It makes me hate it here. It makes me wish I’d worked harder to build a life in a more exciting place. And it makes me feel sorry for the magnificent, game-changing painting Peggy Guggenheim sent to molder in a cultural desert, a city with little to offer its young people on a Friday night but a hot dog cart and a chance to drink beer outdoors in the warm summer breeze, a city just across the river from a place whose greatest attraction is a beaver in the middle of the road.

How did we end up here? I didn’t actually ask the painting out loud, but I looked at Mural a long time. I thought about the brilliant, alcoholic genius who created it; I thought about New York City in the 1940s; and I thought about what it means to end up in a place where you’ll never really click. A place where people keep noticing that you’re different, but don’t understand who you really are. Do people get that you’re a treasure? I thought as I stared at Pollock’s fantastic canvas. Do they even know you’re here? My friends had wandered off. I was alone in the gallery, feeling the hum of the air control system and the subtle vibration of the lighting fixtures. I kept staring at the painting. Are you lonely? I wished there were a way to ask.

Mural is only temporarily at home in Davenport. It was moved from the University of Iowa after floods in 2008 destroyed the university museum. Eventually it will return to the dignity of at least being housed in a university town with a considerable reputation as a literary center, although Iowa City is even smaller than Davenport and similarly hard to reach. Even with the connection to the university, the move to Iowa did not enhance the painting’s reputation. Decades after Clement Greenberg proclaimed Mural a masterpiece, art critic Thomas Crow wrote, “If the painting remains underestimated in the literature, it may be because of its remote location at the University of Iowa.”

So it’s not just me. And while I am not in a position to judge Mural’s place in the “literature,” I trust Thomas Crow. Because even in my best moments and despite the fact that in 30 years here I’ve found wonderful friends and countless sources of delight, I still have to fight my instinctive prejudice about anything that happens to be located in the Midwest: if it’s all that good, what is it doing here?

“Mural,” oil and casein on canvas, 8’ X 13’ by Jackson Pollock, 1943. Image courtesy of www.jackson-pollock.org

* * *

After the excitement of seeing the beaver in Rock Island, my friends and I returned to Davenport, where a riverboat casino had docked just a little ways upstream from the Figge. We wandered in and spent about 30 minutes. The rooms were dimly lit; the walls painted dull beige, mottled with greasy streaks and scuff marks; the red carpet was faded and worn. The clientele were almost entirely senior citizens. Most wore pastel polyester stretch pants and clutched cigarettes in one hand as they used the other to feed quarters into the electronic slot machines. “Where Hope Goes to Die” suddenly seemed prophetic. The denizens of the casino were a depressing counterpoint to the young people we had seen out on the town the night before.

I am willing to concede that Davenport might be a lovelier place than my friends and I were able to discern in the 40 or so hours we spent there. I still think it’s a disappointing home for Mural, and I don’t view the move back to Iowa City as a huge step up. In the same way, I still feel that Minnesota is a disappointing home for me. My life in the Midwest is hardly a cause for existential despair, but I don’t click here. I’m not sure that living in this place has allowed me to become my best, most interesting self. Of course, the failure of life to meet expectations is not solely due to physical location. Mural is still a masterpiece even though it makes its home in Iowa.

On its own website, the University of Iowa admits that “[j]ust why Guggenheim chose to give Mural to Iowa has been a matter of some speculation.” I recently learned that Jackson Pollock’s parents were both from Tingley, Iowa, a small town about 250 miles southwest of Davenport. I have no reason to think Peggy Guggenheim was aware of that fact when she sent her painting to Iowa, no reason to think Jackson Pollock felt any particular connection to his parents’ home state. But the fact that Pollock had roots in Iowa makes Mural’s location seem a bit less random.

We all end up somewhere, and in the end there’s a lot to be said for knowing how to bloom where you’re planted. Not that I’ve developed an interest in gardening. But I’ve gotten better at navigating the broad Midwestern streets, at puncturing the bubble wrap and making some connections. I don’t love the Midwest; I advise my adult children to think carefully about where they will live their lives; and I spend as much time as I can outside of Minnesota. But on the other hand I am lucky: I have four friends here who were willing to travel 300 miles with me just to see a painting.