Early in the morning of April 21, 1914, the north end of the quiet little town of Grinnell, Iowa—home to Grinnell College—was shaken by a terrible explosion. Windows rattled and people were jarred from their sleep. When an investigation was conducted after sunrise, it was revealed that a large rock which had been placed on the College’s campus the previous fall had been attacked with a large charge of dynamite and badly damaged.

That was the main point of an article concerning the event in the Grinnell Herald newspaper. I came across the piece when I was scanning for some other historical information. I was fascinated by the story and began to research the story both back and forward in time through the old newspapers, college yearbooks, and any other documents I could find.

I learned that the College’s students—along with students at many other colleges and universities—followed a tradition called the “class scrap,” which was essentially a wrestling match between the boys of the sophomore and freshman classes. These contests started at Grinnell sometime in the 1870s. They were a sort of capture-the-flag game in which the object was to capture and tie up all of the members of the opposing class. After a night spent camping out in different parts of town, often with skirmishing between small groups of marauders, the two groups would meet on campus at a predetermined time for a final brawl. Often times hundreds of spectators would be waiting to watch the fun, and the results were usually reported in the student newspaper, the Scarlet and Black, along with coverage in the town newspapers. The local papers covered the scrap as if were any other sporting event.

As sometimes happens, even today, the scrappers’ youthful energy and enthusiasm would sometimes overpower common sense. During the scrap of 1907, for instance, the freshmen camped out in the men’s gymnasium. The sophomores surrounded the building in the early morning and used crowbars to pry up the heavy stone steps, which they then leaned against the entrance doors. The freshmen simply opened the large window in the director’s office and climbed out. While the ensuing battle lasted for an hour and a half, the school Administration’s anger about the incident lasted considerably longer.

In 1911, the freshmen camped out in a friendly farmer’s barn somewhat out of town. Someone tipped the sophomores off about the hiding place, and they quietly moved in to surround the barn. The freshmen refused to come out and fight and the sophomores were unable to break into the building to get at them. So, while his classmates blocked the barn doors, one sophomore returned to campus and stole a container of Bromine from the chemistry lab. Bromine is nonmetallic element that is liquid at room temperature. It is quite dangerous to handle because it can cause severe skin burns and is very irritating to the lungs and eyes. When the young man got back to the barn, he opened the container and threw it in a window. The chemical made all of the younger boys terribly sick and badly burned the arm of a student on whose arm it it landed. Almost needless to say, the battle was over very quickly after that. As one might expect, many people in town, and most certainly the college Administration, took a very dim view of such a breach of fair play and decency.

Troubles for the class scrap tradition came to a head in 1913 when a student at another school was killed during another, similar campus battle. Grinnell College President Main, who had never favored the tradition, threw his considerable influence behind the notion that the class scrap should be stopped forever. The presidents of the two classes finally agreed with President Main, and they were able to convince their classmates as well. They conducted these negotiations in secret, without letting either the other students or the public know, because they had a dramatic plan for making the announcement.

The night before the scheduled contest, the two classes left campus separately, ostensibly to camp in separate areas. In actuality, they met in a farmer’s field two and a half miles west of campus, along the route of what would eventually become Highway Six. There, just at the edge of the road, was a large granite boulder which had long posed a danger to passing traffic. The farmer who owned the field was blasting the boulder into smaller pieces so that it could be moved away from the road, and the students obtained a large fragment, loaded it into a wagon, and hauled it back to town. By the time they reached the campus, many dozens of spectators had gathered to watch the expected fight. Instead, the students placed the Rock in the middle of central campus, after which there were speeches by President Main and the two class presidents, declaring the end of the class scrap tradition and promising peace for all time.

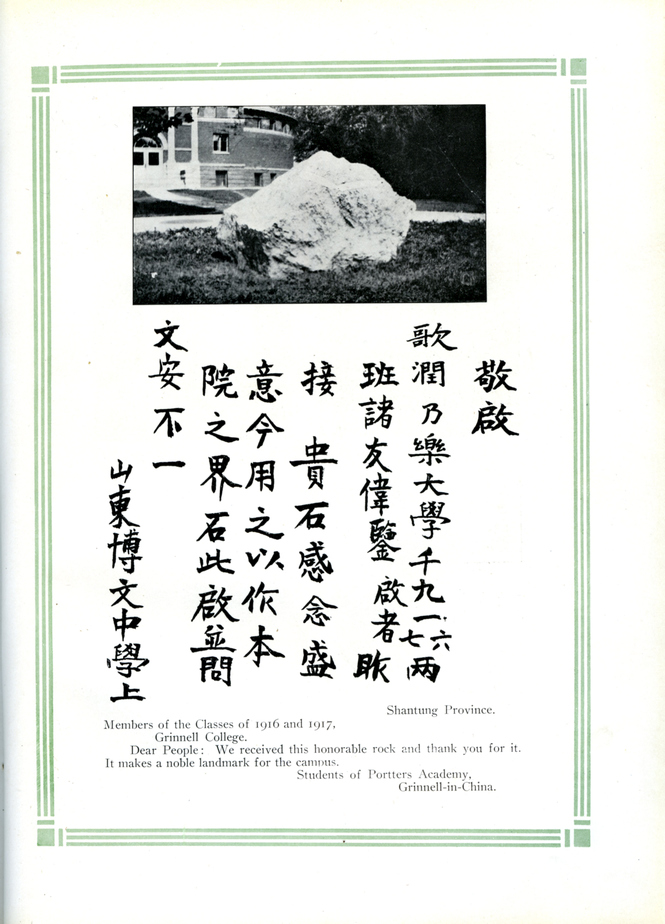

A spoof from the 1917 issue of The Cylcone, Grinnell College’s yearbook, in which the disappearance of the Peace Rock was explained. According to the note, the Junior and Senior classes of that year made a gift of the rock to a school in China, and the students sent this thank-you. the note offered no explanation for the presence of the Grinnell College women’s gymnasium in the picture.

Not everyone approved of the loss of this decades-old tradition. In the spring of 1914, someone painted the Rock bright red and added the class year ‘18 in black. It was a week after this that the aforementioned explosion took place, blowing off a portion of one end, and waking up the north end of Grinnell with the sound and concussion of the blast.

Nor was this the final indignity the Rock was to suffer. About a week after the explosion, someone dug a hole next to it, rolled it in, and covered it over, apparently forever. The two classes included a photograph of the Rock in one yearbook, and a mocking picture of its burial site in another.

Second-year Grinnell student Lauren Edwards digs for the Peace Rock in the area where Byron Hueftle-Worley’s research said it would be, near new construction on the College’s Quad. Photo by Justin Hayworth.

The class scrap returned the next school year in the form of a game of pushball, which is somewhat similar to a soccer game, but played with a leather ball that is six or more feet in diameter. After that, the scrap continued as the traditional wrestling match for another few years. Some vestiges of the tradition lasted at least until the 1960s as much more restrained competitions between the two classes.

After researching the Rock and its history, I shared the story with John Whitaker and Kathy Camp, two anthropology professors at Grinnell College who are also experienced archaeologists. The photographs in the yearbooks gave us enough information to locate the likely position of the Rock within a few feet, and John and Kathy worked with the college Administration to get approval to dig up the Rock during some construction work that was taking place on campus in April, 2017. They used the excavation of the Rock as a part of their field methods class, with students doing most of the work and learning proper archaeological procedures in the process. Employees of McGough Construction, which was doing the construction work on campus, were interested and generous enough to help lift the Rock out of the hole and set it in public view. When the construction is completed, the Rock will likely be displayed as a physical reminder of an otherwise forgotten tradition.

The Peace Rock, brought fully to light for the first time in 103 years. Photo by Justin Hayworth.

It’s interesting to note that a bit of further research has revealed that other groups followed the students’ lead, using pieces of the original large boulder for historical markers. One large piece was used for a marker near the site of the Long Home, the first house built in Grinnell. Another was used for the tombstone of Billy Robinson, Grinnell’s pioneer aviator, who was killed near town while trying to set the world’s record for high altitude flying. A third was used to mark the homestead of J. B. Grinnell, the town founder.

Byron Hueftle-Worley stands by the newly excavated Peace Rock with Grinnell Anthropology Professor John Whittaker. Whittaker supervised students from his Archaeological Field Methods class in conducting the dig. Photo by Justin Hayworth.

The sad and ironic twist to this story is that some of the students who placed the Peace Rock on campus would not complete their college careers in peace. Two months after the Rock was buried, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo triggered the start of World War I. When the United States entered the war three years later, most of the male students on campus, along with many of the recent graduates, enlisted in the military. Many of them served overseas, and some never returned. For all of the young men who had been involved in declaring peace for all time, peace had taken on a much more complicated and

difficult meaning.

A new generation of Grinnell students makes the Peace Rock’s acquaintance. Photo by Justin Hayworth.