The Monsanto Corporation, a multinational agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology corporation headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, is a looming presence on the American industrial landscape. Since its founding as a pharmaceutical firm in 1901, Monsanto has had a hand in many advances which have literally shaped the modern world. Among the products Monsanto or its subsidiaries have developed or produced are the artificial sweetener saccharin, vanillin, aspirin (and its raw ingredient salicylic acid) and such basic industrial chemicals such as sulfuric acid and PCBs. Its research labs helped with the Manhattan Project and later became involved in the development of DDT, “All” fabric detergent, Agent Orange, Astroturf, L-Dopa, and light-emitting diodes. The company was one of the first to genetically modify a plant cell, and in more recent years, through its patents, strategic mergers and acquisitions of the seed businesses of such companies as Dekalb, Cargill and Seminis, Inc., the company has become the world’s largest seed company, parlaying its GMO patents into vastly profitable product lines.

All of this has made Monsanto one of the biggest and perhaps the best-known of the companies one thinks of when the phrase “Big Ag” is spoken. Among the many, many profitable products the company has fielded, one of the most prominent is the herbicide Roundup.

If that name has not become familiar through the company’s advertising, you have only to stroll down the gardening aisle of just about any home center or hardware store in America, and you will find shelf after shelf filled with jugs of the weed-killer whose patent Monsanto has owned since 1974.

There is major disagreement about how Roundup—generically known as glyphosate—works. However, there is general consensus that the chemical’s effects often come not from toxicity, per se, but from the way it interferes with the plant’s metabolism, and its relationship with the soil in which it grows. According to curricular materials available at Indiana University/Purdue University Indianapolis:

Glyphosate is quickly absorbed by leaves and shoots of plants. Once absorbed into the leaves, glyphosate cannot be broken down. The glyphosate moves quickly through the plant and accumulates in areas of active growth called meristems. Spraying a plant [which has not been genetically modified to resist it] with Roundup results in a lack of protein synthesis in that plant…. Within a week or so, many plant tissues and parts slowly degrade due to lack of proteins. Death of the weed ultimately results from lack of nutrients and dehydration a week or so later. 1

Alternatively, the work of Johal and Huber 2 suggests that glyphosate takes plants down by obstructing their formation of compounds which protect them from pathogens normally present in the soil, which then kill them. In their experiments in sterile greenhouse soil which lacked those pathogens, glyphosate-treated plants were stunted for a short time, but then bounced back.

Whatever the mechanism, there is no doubt that in the real-world environment of the farm field, glyphosate works. In recent years, Monsanto has also begun marketing glyphosate to farmers as a way of “finishing” their crops—that is, killing and drying out the plants to make harvesting the grain quicker and easier. This use, and the ubiquity of “Roundup Ready” soybeans and corn—which have been genetically modified to fend off the herbicide’s effects while the weeds in the fields around them die—have resulted in huge increases in Roundup’s sales: according to a 2011 EPA report 3 quoted by the Pesticide Action Network, (PAN) between 2001 and 2007, use of glyphosate more than doubled, growing from 85-90 million pounds to 180-185 million pounds. Another report, published in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe, lends more historical context to this increase:

Since 1974 in the U.S., over 1.6 billion kilograms of glyphosate’s active ingredient have been applied, or 19 percent of estimated global use of glyphosate (8.6 billion kilograms). Globally, glyphosate use has risen almost 15-fold since so-called “Roundup Ready,” genetically engineered glyphosate-tolerant crops were introduced in 1996. Two-thirds of the total volume of glyphosate applied in the U.S. from 1974 to 2014 has been sprayed in just the last 10 years. 4

Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson

In 2013, 210 million pounds of glyphosate were sprayed on corn and soybean fields, and the total used for agricultural purposes was 295 million pounds in the U.S. alone. 5 In 2014, farmers sprayed enough glyphosate to apply ~1.0 kg/ha (0.8 pound/acre) on every hectare of U.S.-cultivated cropland and nearly 0.53 kg/ha (0.47 pounds/acre) on all cropland worldwide. 6

This translates into big profits for Monsanto. In 2015 alone, the company notched nearly $5 billion in sales, with nearly $2 billion in gross profits from herbicide products, mostly Roundup. 7

But while use of glyphosate has killed farmers’ weeds and boosted Monsanto’s bottom line, a growing chorus of voices has begun questioning whether the increase in harvests and Monsanto profits is coming at the expense of our collective health.

Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson

In late August of 2017, Rootstalk publisher Jon Andelson and Associate Editor Mary Rose Bernal had a long discussion with someone who has been asking these questions: large-animal veterinarian Arthur Dunham, whose practice is in northeastern Iowa, in the small town of Ryan. Dunham’s medical training has enabled him to do a deep dive into the science surrounding glyphosate, and he has had a ground-level view of the compound’s effects on the animals he has encountered in his practice. As he educated himself on the subject, what he found at first intrigued, then ultimately alarmed him. He has become convinced that glyphosate has deeply penetrated too much of our food supply and some of our water supply, and that it is causing both short- and long-term damage to our ecosystem, as well as to the health of both livestock and humans.

Rootstalk: Can you tell us a bit about the history of glyphosate?

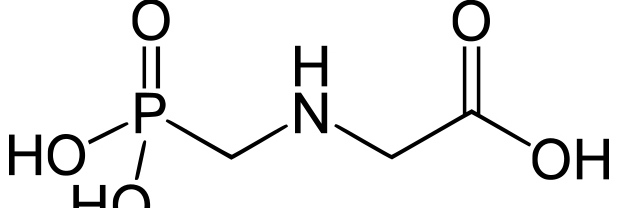

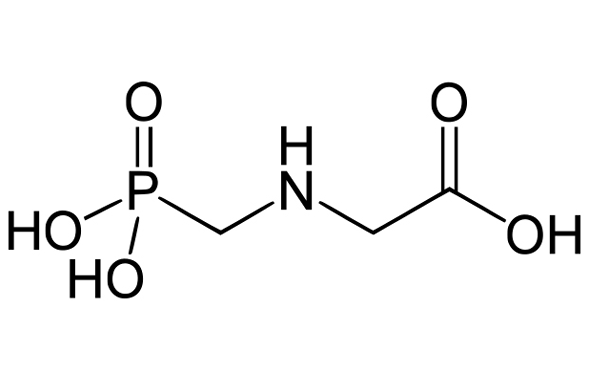

Dunham: Glyphosate is the active ingredient of Roundup, really the most popular herbicide in the world. It’s N-phosphonomethyl glycine… a phosphonate chemical [that] was patented first by Stauffer Chemical company in 1964 as a descaler for metal pipes. It was then patented in 1974 [by Monsanto] as a herbicide. And in 2010, it was patented as a human antibiotic and parasite control agent [because] it has activity against gonorrhea and malaria.

Rootstalk: Is glyphosate being used as an antibiotic today?

Dunham: Glyphosate has [never actually been] used as an antibiotic. [Monsanto] applied for the patent in 2002 and they got it in 2010, but they’ve never [sold it as such]. [Glyphosate’s] main use is as a herbicide and a drying agent. By drying agent, I mean that [farmers] are using it pre-harvest to dry down the crop, to kill it.

Rootstalk: Why has Roundup/glyphosate become the most widely used herbicide?

Dunham: Well, number one, it’s cheap. And the other thing is, it’s been super-effective. It’s let farmers farm more acres with less labor. One farmer can handle way more ground.

Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson

Rootstalk: How did you become interested in it?

Dunham: I got more interested in this whole thing as a veterinarian in 2005-2006, [when] I had five different dairies where I had stillborn, aborted calves. I sent in their livers to Iowa State University after reading my Dairy NRC [Nutrient Requirements for Cattle], and I had them check them for [the mineral] manganese. Their machine couldn’t even find any.

Rootstalk: And manganese is necessary for normal fetal development….

Dunham: [Right.] So then, I talked to the fellow that wrote the mineral section of the Dairy NRC and he said, “Well Art, there’s plenty of manganese in No. 2 Yellow Corn. There’s plenty of manganese in soybeans and there’s plenty of manganese in haylage [livestock feed made from perennial forages such as grasses and legumes] and corn silage.” I kept saying, “Well, how come the machine at Iowa State [can’t find the nutrient in the calves’ livers]?” And the guy I talked to didn’t have a good answer.

One of the dairymen [whose calves I was looking at] was mad at my two partners and me because we weren’t really helping him. Our vaccine program wasn’t working that good. He had John Deere tractors, so he had a copy of the [company’s magazine], John Deere Furrow, for the spring of 2007. The client put me onto it; he [understood what was going on] before I did. He shoved the issue in front of my face, and he said, “Art, maybe you’ll be interested in this.” Well, I sure was!

In that issue, there was an article by this Purdue University professor named Don Huber [who was] talking about glyphosate tying up manganese, and maybe we should start looking for an alternative. I tried to get the experts at Iowa State University to phone him up. They wouldn’t do it, so I did. And then, see, that’s where we developed that relationship, in 2007. He’s retired now but still living in Idaho. He’s originally from out there. And when I say he’s retired, he’s still working. He’s [consulting] in Australia right now. He’s 82, and he’s still working on this.

[Huber] worked at [the United States Army Medical Command installation at] Fort Detrick [Maryland] on biological warfare agents, so he’s an expert on ricin and Agent Orange. He was the head of our government’s Plant Pathogen Threat Committee for 25 years…. He has consulted [on crops] on every continent but Antarctica. [So] I really got onto [glyphosate after I talked to him]. I still remember the phone call. [I had] called him up two weeks before [this], and I didn’t hear from him and I didn’t hear from him, and I thought he’d just blown me off because I tend to ask questions and then see if people can answer them, and then I never hear from them. But he phoned me and apologized for taking so long to get back to me. He said: “I’ve been in Russia on government business.”

Anyway, in that conversation I [brought up] the article he wrote in the John Deere Furrow, and I said, “You’re from Purdue. It’s a land grant college like Iowa State, isn’t it? It’s pretty brave to come right out and say ‘We ought to be looking for an alternative to glyphosate!’ How could you write that in there? How do you get any grant money? How can you do any studies?”

Rootstalk: How did he answer?

Dunham: He’s a little bitty guy, but he has a real deep bass voice. He went, “Heh, heh, heh, Art; I’m 72 years old, and I’m supposedly retired. I don’t have to [publish] or apply for grant money anymore, and I can call it like I see it.”

Rootstalk: And this was when he said glyphosate might be the issue?

Dunham: Yeah. [In] his article, he talks about the fusarium mycotoxins [fungal contaminants of food and animal feed] that I’m seeing, and that [he said] glyphosate helps increase the risk of. So, everything just…. It just made sense….

Rootstalk: How did Don Huber get interested in glyphosate?

Dunham: He did the half-life studies for Monsanto in the early 70s, to get it approved as a herbicide. [Later], he realized that his science was flawed. So now he’s trying to make amends for that by getting the word out.

Rootstalk: The science was flawed? How?

Dunham: Glyphosate [concentrates at the plant’s growth points—the joints of the stalk, the root-tips, and the grain]. When [Monsanto] did the studies on corn to determine the half-life [of the chemical], they did it after they’d sold the corn grains, so they got rid of a third of it there. Then they sold the corn [stalks for] fodder, and because [glyphosate concentrates] in the joints of the stalk, they got rid of another third of it there. So that just left the third that went to the root tips to study. But [when they tested it] they didn’t do the studies in soil. They did the studies in beakers of solution at room temperature.

Rootstalk: So, they weren’t measuring the full concentration of glyphosate in the environment.

Dunham: [There are only] certain bacteria and fungi that can break [glyphosate] down. The more bacteria you have in your soil, the more diversity you have, [and the shorter the period of time] you’ve used [glyphosate], the faster it will break down. So now they’re figuring out that [glyphosate’s] half-life can be as long as 11 years. So, [over time] it’s [been] building up. That’s why, as a veterinarian, I didn’t really start seeing issues with it—let’s see, we started using it in ’74, and then we didn’t start using it big-time until 1996 when we had Roundup Ready beans and in 1998 with Roundup Ready corn.

Rootstalk: And one of the selling-points of Roundup-Ready crops was that farmers wouldn’t have to use as much herbicide for it to be effective….

Dunham: Remember, our whole ag business industry [said]: “Oh, we’ve got to have GMO because we’re going to use less chemical.” [So, with Roundup Ready crops] we maybe used fewer of the other herbicides that we said were more risky—which, actually, when we knew they were risky, we handled them more carefully. We couldn’t put them on indiscriminately after the crop was alive and growing, and we didn’t have to worry about near as much carry-over because they rinsed off. And there’s nothing in the Roundup Ready plant that breaks down glyphosate for you.

Rootstalk: So, glyphosate was building up in the soil because farmers were using more of it.

Dunham: Yes. It’s just the opposite of what we hear.

When we drove the price of corn up—when we really started pushing [corn-based] ethanol—wheat wasn’t priced that good. So, Kansas farmers, Nebraska farmers, Oklahoma farmers, that had center pivot irrigation and had enough well water… switched to corn, and it was Roundup corn. Then, when things got a little bit cheaper on the corn they tried switching back to wheat. Guess what? You’ve got enough [glyphosate] carry-over, and unless you’re getting lots of feedlot manure and you’re doing some other things that have some bacterial action to break down [the glyphosate], when you plant your wheat, you’ve got a pitiful stand.

Rootstalk: Because the glyphosate is still in the soil.

Dunham: [Yes.] And Monsanto has paid out considerable amounts of money [in legal settlements] without anybody knowing about it, because the way our court system works, see, when the farmer gets paid, he has to sign, “I can’t say anything.” And, again, only because of the group of other concerned people I’m working with, do I know anything about that.

Rootstalk: So, what would you say are your main concerns about glyphosate?

Dunham: My main concerns are human. And soil.

Dunham explained that glyphosate’s impact on livestock and humanity stems from a cascade effect: when glyphosate is applied to a crop in the field, in addition to killing undesirable plants, its antibiotic properties damage the soil bacteria which normally add to soil tilth and organic matter. This—along with the heavier application of glyphosate to fields in which Roundup Ready crops are growing—leads to a concentration of glyphosate in the soil itself, as well as percolation of the chemical into groundwater. With glyphosate remnant in the soil, unless the farmer continues to plant glyphosate-resistant crops, yields in treated fields can fall.

Then there are the chemical’s negative effects on livestock. When animals consume Roundup-treated plant material, it causes an impoverishment of the animals’ gut-biome, making it harder for the animal to absorb micronutrients—including the manganese whose absence Dunham noted in the fetal calves of his clients’ dairy herds. This leads to animals which, when they don’t die in utero, often suffer health problems before they reach market.

Researchers have begun to look into whether these effects are also being passed up the food-chain to humans. The thinking is that, with glyphosate accumulating in plant tissues and (in smaller amounts) in the animal protein we consume, as well as in some of the water we drink, the chemical has begun to accumulate also in the tissues of the human population, leading to a host of medical problems.

Rootstalk: So, you’ve talked about glyphosate’s effect on fetal dairy cattle—their inability to absorb manganese. Can you describe some of the other effects on the animal and human populations which some researchers are linking to this growing concentration of glyphosate?

Dunham: Well, [one effect is from Vitamin] B-12 deficiency [which leads to] demyelination. This is the degrading of the myelin sheath covering the nerve cells—just like having electrical wires that don’t have good insulation. So, it could be your spinal cord. It can be peripheral nerves. And animals and people have all sorts of demyelinating disease processes.

Rootstalk: Can you cite any instances in which you’ve seen this problem crop up?

Dunham: Probably in 2010 or 2009—it was after I met Huber—there was another person, Dr. Mike Sheridan, a world-wide known swine consultant from western Canada. who had been working with these big farrowing set-ups in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, for a great big Hutterite colony, and they’re kicking out 130,000 hogs a year, farrow-to-finish.. [This vet had] run into a bunch of animals he called “squatter pigs” because they’re going down in the rear end. Three percent of these 130,000 hogs are going down in the rear end. Well, [in this operation they didn’t] feed corn. They [fed the pigs] barley, wheat, and rye [which had been dried down with Roundup]. They fed that to the sows. And the best way for a baby to be Vitamin B-12 deficient is if the mother is deficient. So, they were feeding [Roundup-finished] grain to both the sows and the [juvenile] pigs.

This guy ended up sending tissue [from these “squatter” pigs] to two vet schools. He cut into their spinal columns and sent them in…. And they looked at it and they told him that it was Vitamin B-12 deficiency causing this. Well, then, he knew he really had something problematic, so they sent it to a human medical school and they told him the same thing. So… he decided to put in 10x Vitamin B-12 in the feed. It isn’t that expensive. And he put in more [Vitamin B-9], too. [This] only lowered the incidence maybe in half.

Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson

This vet was on the American Association of Swine Veterinarians listserve, so he puts a question on there either in 2009 or 2010 and he says, “Can somebody help me? What the heck’s going on?”

Rootstalk: Because the B-12 and B-9 supplements should have taken care of the B-vitamin deficiency….

Dunham: It should have. So, he had his phone number on [his email]. So, I phoned him up, and I said “Mike, is there any chance that Hutterite colony quit windrowing their barley, wheat, and rye and they started spraying it dead with glyphosate?” And he says—I still really remember this conversation too—he says, “WHAT? What are you talking about?” And I told him “You’d better check it out.”

So, he checked it out. [The Hutterite operation was] big enough, so they were buying some of their feed, too. So… they went back to [drying their grain in windrows]. And guess what? Their problem disappeared.

Too much of [the grain crop is desiccated using glyphosate]. I’m not saying all [of it]—but a lot of it is. And so, [glyphosate acts as an antibiotic] when you eat the wheat. [This is where] I get arguments from my veterinary colleagues because they say, “Oh, it’s too low a dose. It’s too low a dose.”

And yet [look at what we’re doing] in hog practice…. [We’re] trying to cut back on low levels of feed-grade antibiotics so we don’t create resistance. And we’re trying to be more responsible. We’re using [glyphosate] as a herbicide and throwing it at everything. What I’m trying to tell you is that, in parts per million—when you’re dealing with an aminoglycoside antibiotic, like Neomycin or Gentamicin, Amikacin, and if you are trying to kill off E. coli in the gut of a pig with post-weaning scours—you don’t have to dose him at one milligram per pound of bodyweight, or two or three. You can [get that effect with] a real small [dose]—just in parts per million in the animal’s gastrointestinal tract. With the glyphosate [antibiotic] patent, they come right out and say one to two parts per million is an adequate dose. And then we’re spraying half a part per million or better. And then we’ve got carry over….

Photo courtesy of Jon Andelson

Rootstalk: Are there other researchers you can mention whose work supports these conclusions?

Dunham: Dr. Monika Krüger 8 is another real important [person]. Huber got invited to talk at a conference in Europe, and she got invited to the same conference. That’s how they got together. She’s a veterinarian, but she never was a practicing veterinarian. She’s a researcher. She’s retired now, too. She was at Leipzig, Germany, at the University of Leipzig. In northeast Germany. She was behind the Iron Curtain, and Monsanto and agribusiness knew nothing of her. I met her in China in 2014. Then I saw her again, [when] she testified [in October 2016] at The Hague [concerning glyphosate] 9.

She’s got a Ph.D. in microbiology, a Ph.D. in mycology (the study of fungus), a Ph.D. in veterinary pathology, and she worked at a human hospital before she retired. Her field of expertise is Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. And she’s a botulism expert.

So… anyway, she’s shown that at one tenth of one part per million in the gut, that’s a high enough level of glyphosate that it kills off Enterococcus faecalis and faecium that somehow produce bacteriocins [toxins produced by bacteria which inhibit the growth of similar or closely related bacterial strain(s)], which normally keep Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium butyricum, Clostridium novyi and Clostridium haemolyticum from producing botulism neurotoxin.

For botulism [to form], you have to make a couple of mistakes. You’ve got to make your haylage a little too wet, [which causes] Clostridium butyricum [to] come in. If you’re feeding all sorts of Roundup corn and Roundup silage, well then, “Boom.” You get this toxico-infectious botulism. It’s even worse than the old botulism that our experts know about, [which happens] when you have a dead critter in the pit silo and you grind it up in the feed and you lose half your herd all at once. That’s not what I’m seeing. What I’m seeing is a few dying, just picking at them. It’s an ongoing problem because they’re producing the neurotoxin in their intestinal tract.

Monika Krüger developed some test kits [which would detect this problem] that I tried to get over here. She was willing to get them over here. Because [currently] in the U.S., the only way we have to diagnose botulism is you send your tissues [to a vet school for forwarding to a laboratory. Here, we send tissues to] Iowa State or the University of Wisconsin vet school, and then they send [the samples] up to Metabiologics in Madison, Wisconsin, that makes botox, because they have a mouse colony and they inject the mice. If the mice die, you have it. Well, the problem is that the cattle, horses, pigs, wild pigeons that I’ve seen it in—they are all more sensitive than mice. So, when we get this real low level, we can’t confirm it. And in modern medicine…. [when you diagnose lockjaw in livestock, it’s caused by] Clostridium tetani, they get stiff as a board after a castration infection. Nobody ever diagnoses [that] by culturing Clostridium tetani, though. It’s next to impossible to grow. Nobody diagnoses it by finding the neurotoxins, because it’s in parts per trillion, and they can’t find it. Well, botulism is the same way, basically. And yet, you can send them pictures of the cows with their tongues hanging out and drinking like cats. So, I can diagnose it clinically, but I can’t prove it in a lab. And in modern veterinary medicine and in modern human medicine, if you can’t prove it in a lab, it doesn’t exist.

[And here’s another thing]: it only takes maybe one tenth of one part per million [of glyphosate] to kill Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum. They are two real important bugs in the crop of a bee. I’m so dang disgusted there, because everybody’s leaving glyphosate out of [the conversation about colony collapse]. They’re all talking about the [neonicotinoid pesticides] that are coating the seeds—yes, they’re part of it. But, if you throw glyphosate into the mix, the bees basically are getting these mites and this Colony Collapse Disorder because they’re starving to death.

See, they’re like a cow. The cow’s rumen is kind of like the community of soil organisms around a plant’s roots—a big fermentation vat. And so, [when glyphosate is] in there, it’s like any other antibiotic, it sort of screws things up! And we’re trying to ignore it. [The] GMO people are saying “Art, oh, you’re full of [it] because we’ve been feeding it and we see nothing.” Well, that isn’t really science. They’ve never done any side-by-side comparisons.

Rootstalk: So, let’s go back to the effects on humans. Can you talk about the linkage between glyphosate and human disorders?

Dunham: Well, here’s [a little background first.] If you get involved in medicine, the pharmaceutical companies and the ag chemical companies, everybody is all hooked up together. And it’s just hard to do any out-of-the-box thinking. Dr. Stephanie Seneff 10 —she just retired, but she was the head of the artificial intelligence division at MIT. I think she’s got a grandchild or somebody with autism. She got all these biology degrees before she went into artificial intelligence.

So, anyway…Huber got invited to talk at the same meeting that Dr. Seneff got invited to talk at. And she’s known for a long time that there had to be something that we’re eating or that is in our environment that’s helping cause autism. And she listened to Huber and it’s just “Ding-ding-ding-ding-ding!!”

[Then there’s] Nancy Swanson 11 ; she was a biophysicist for our Navy. She lives in the state of Washington. She’s part of a lawsuit 12 out there. Monsanto labeled her, “just a kook.” [That’s] far from true. [If] you look at things that are connected with the science that we know about glyphosate, and [in addition to the other disorders already mentioned], you look at Type Two Diabetes, it fits in there. Alzheimer’s, Parkinsonism, pancreatic cancer—some of them fit and some of them don’t. Anyway, when Nancy Swanson gets all the [Centers for Disease Control] data and then looks at these correlations 13 , and the increase in glyphosate use since 1996 and ’98? Most of them are 97 percent plus! And, if you look at low-density lipoprotein or bad cholesterol supposedly, and Coronary Arterial Disease, I think the correlation is 62 percent. Yes, we need more science, but we have refused to even look at it!

Rootstalk: And Monsanto’s doing whatever they can to stop the research?

Dunham: Sure, they are! They bought up most of the bee research firms that back up what I said about bees 14 ….

[Then there’s] gluten intolerance. What we’re doing is [by continuing to use glyphosate on crops], we’re changing the bacterial flora in our gut, and then we get leaky bowel. Then the gluten, instead of getting digested in your intestine, it leaks into your system. So, it’s like a kid that gets stung by a bunch of bees when he’s little. Then he gets allergic. See, you want the wheat to get digested in your bowel and not get into your system. Once it leaks into your system, even if you get the glyphosate out of your diet, if you stimulate your immune system enough and get allergic to it, you’re going to be allergic to it forever!

While glyphosate’s alleged effects on plants and animals take center stage in many minds, there are also concerns about the chemical’s possible effects—through its antibiotic action—on the health of the soil’s biome. There are fears that long-term application of glyphosate to croplands is leading to the degradation of soil’s load of organic matter, its susceptibility to erosion, and its ability to store carbon. If the soil’s ability to sequester carbon is degraded, this in turn contributes to the worsening of global warming. Art Dunham spoke about these effects at length.

Rootstalk: You mentioned soil effects earlier. Could you say more about that?

Dunham: Today…we’ve got everybody believing that no-till and minimum-till agriculture are way better for soil. And [it’s true that], now that farms are bigger, you can’t mold board plow 640 acres, [because] you’d have all sorts of erosion. [But] of course, everybody that no-tills and minimum-tills has to use glyphosate [to keep the weeds down]. And so, remember that glyphosate is an antibiotic—it’s breaking down the soil organisms that form the aggregation [clumps of soil particles that are held together by moist clay, organic matter (like roots), gums (from bacteria and fungi) and by (fungus filaments)] 15 , [and that means our] soil organic matter levels are going in the toilet. They’re going down to two percent.

Francis Thicke 16 . He knows what he’s talking about. I got this from him first.

Rootstalk: He’s a dairy farmer in Fairfield.

Dunham: But he’s also a Ph.D. and was a USDA soil scientist. So, I got this from him and then I double checked it. I’m sure it’s correct. In Iowa, we’ve got all sorts of soil, but [in aggregate] it’s the best soil in the world, and we’re down to three [percent organic matter] and under. If it’s two percent or under it can only hold a half inch of rain an hour. If you gain two percent on that, you can hold another 6 to 8 inches an hour! If every farmer in the world… would raise their soil organic matter by two percent…

Rootstalk: …that would have a positive effect on soil loss and erosion.

Dunham: [With Roundup Ready seed and the attendant application of glyphosate] you don’t get to store that much carbon below the ground, so you’re lucky if you hold your organic matter and keep from losing it. [If you were growing] non-treated corn [and not applying glyphosate and killing the microbes in the soil], you could raise your soil organic matter by 30 tons [per acre] below the ground. [You could] raise your organic matter by half a percent per year. And, if every farmer in the world raised their organic matter by two percent, you not only hold more water for both flood situations and drought, you would store an amount of carbon equivalent to all the carbon dioxide generated by mankind in the last one hundred years.

Rootstalk: The implication is that glyphosate is playing a part in climate change. One last question: Are there any countries which haven’t approved glyphosate for agricultural use?

Dunham: Uh, practically everybody’s approved it at one time or another. [But] Sri Lanka has outlawed it because they’ve had so many people with renal failure—people in their 20s and 30s, and they don’t have hospitalization as adequate as us and they have no money, so they’re dying. So, Sri Lanka is the bravest country in the world right now

And then there’s Germany. Germany [was] the first major nation [to put restrictions in place]. [Because] Germany outlawed [glyphosate’s use in] all spray-drying of crops for human and animal use.

Rootstalk: What moved them to do that?

Dunham: Well, the main reason they did it is because, well, you can’t efficiently brew beer [with glyphosate-finished grain]. See, the barley farmers started to spray-dry the crop [with glyphosate] and then they didn’t tell the breweries they were doing that. And then the breweries were having a harder time brewing their beer. [They decided the antibiotic effect is] for real, so they’ve got to go back to windrowing [the barley crop] and letting it sun-dry.

* * *

In recent years, mounting evidence like that which Art Dunham related above has begun to provoke widespread resistance to glyphosate use. Belgium, Malta, the Netherlands and (as Art Dunham mentioned) Sri Lanka have all banned the chemical’s use within their borders 17 , and French President Emmanuel Macron has signaled France’s intention to follow suit within the next three years. 18 How many other countries will join in this ban remains an open question, but in 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) ruled that glyphosate was “probably carcinogenic,” 19 and in the spring of 2017, the State of California’s Environmental Protection Agency put glyphosate on the list of known cancer-causing agents. 20

In the wake of the IARC’s finding, the matter has also shown up on numerous court dockets. More than 1,100 lawsuits have been filed against Monsanto in the U.S., with claimants alleging that glyphosate caused their non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a type of blood cancer 21 . Monsanto is facing another class-action lawsuit in Wisconsin 22 , where claimants are saying the company falsely said Roundup was safe, when it actually has adverse effects on human gut bacteria.

News accounts during 2017 which detailed the unfolding glyphosate drama paint starkly different pictures of the issue. For instance, one New York Times article 23 , published in March, detailed what appears to be an organized Monsanto effort to manipulate research and orchestrate a public relations assault on Roundup’s critics. Another pair of articles, published a few months apart by Reuters, suggested that glyphosate’s carcinogenic properties are based on flawed science 24 , and that the IARC’s report “edited out” evidence that glyphosate was non-cancer-causing. 25 The truth or falsity of these claims has yet to be definitively established.

There has also been strong pushback coming directly from organized ag and industry. On November 27, 2017, despite having received a Greenpeace petition signed by 1.3 million in favor of the glyphosate ban 26 , the European Union Commission’s Appeal Committee voted to approve Monsanto’s and other glyphosate makers’ license to sell the chemical in Europe. Germany’s Agricultural Minister Christian Schmidt provided the controversial swing vote in the EU’s decision 27 , reportedly defying the orders of the German Environment Minister Barbara Hendricks—and of German Chancellor Angela Merkel 28 —when he voted in favor of the glyphosate reprieve. However, the license will be in force for only five years—a period far short of the 15 years which proponents of the chemical had sought 29.

Amid all this back-and-forth, one thing seems clear: the glyphosate battle will continue to be fought out in the world’s legislatures and courtrooms, as well as in the court of public opinion. And it seems equally clear that glyphosate’s status in agriculture won’t be a settled matter for a long time to come.

“Show Me,” Oil on canvas, 12” x 60”, by Jane Pronko, 1987

2 Johal G. S.; Huber D. M. Glyphosate effects on diseases of plants. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 31, 144–152

4 https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s12302-016-0070-0

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glyphosate#/media/File:Glyphosate_USA_2013.png

6 https://enveurope.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s12302-016-0070-0

7 https://www.fool.com/investing/2016/05/26/how-much-money-does-monsanto-make-from-roundup.aspx

9 https://www.ecowatch.com/monsanto-tribunal-2043486785.html

12 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/business/monsanto-roundup-safety-lawsuit.html

14 https://www.huffingtonpost.com/richard-schiffman/the-fox-monsanto-buys-the_b_1470878.html

15 http://www.soilhealth.com/soil-health/biology/formation.htm

17 https://www.naturalnews.com/2017-09-30-five-countries-have-banned-glyphosate-in-the-wake-of-recent-lawsuits.html

19 https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/glyphosate-cancer-data/

21 https://www.naturalnews.com/2017-09-30-five-countries-have-banned-glyphosate-in-the-wake-of-recent-lawsuits.html

22 https://www.ecowatch.com/glyphosate-lawsuit-wisconsin-2445162053.html

23 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/business/monsanto-roundup-safety-lawsuit.html?_r=1

24 https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/glyphosate-cancer-data

26 https://news.sky.com/story/germany-swings-eu-vote-on-controversial-weedkiller-glyphosate-11147020

27 https://news.sky.com/story/germany-swings-eu-vote-on-controversial-weedkiller-glyphosate-11147020

28 https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-says-christian-schmidt-did-not-follow-protocol-on-glyphosate-vote