There are battles which never make the news, at home or abroad. Yet, they are as deep and hard-fought as any you will find. The battles are over the will of the people, the dictates of a distant capital, and the struggle to maintain a sense of place in a dynamic world. In a constitutional democracy, there is an obligation to follow the law. But when some laws hurt or threaten, is there an equal mandate to resist?

I spent my last year traveling and teaching in Norway as a Fulbright Scholar. My sojourns in that northern kingdom were mediated by my Wisconsin roots and an adulthood spent in Iowa. I found that the people, culture, climate, and geography of Iowa and Norway intersected in various ways—some obvious, as is so with their ethnic roots, while others are more nuanced, as with the similarities that can be found in the cultivation of salmon and the operation of Iowa hog lots. In my travels, I found that some of the same battles which we fight out on the prairies of Iowa resemble those fought out along Norway’s fjords. These places—so geographically distant from each other—share a surprising bond in how they sometimes have to fight to maintain their identities and existence in a word which often seems to have turned its back to traditional communities.

If you think Norway is a rich country with no problems, then you are mistaken. Does the Kingdom of Norway have wealth? Yes, of course. But there are pressures brought to bear on its society by the difficulties of modern governance and the competing demands of neoliberal disruption and conservative parsimony. During my time there, I saw that these pressures are evident in the small towns of Norway. Many of struggles and fears I discussed with people around Norway sounded uncomfortably similar to those I knew first-hand in the Hawkeye State.

In one town in the south of Norway, Agder, I commiserated with teachers about the pressures of school consolidation. Theirs was a small but a proud school, with a rich history and an intimacy between faculty, staff, students, and the community of which I was envious. “According to the numbers…,” is the way every tight-fisted bean counter starts the argument that per- pupil costs are too high, and that’s how it was in Agder, too. I personally find it galling when we attribute agency to inanimate things like numbers. Numbers never say anything; only people do. If you have been convinced that numbers speak, then it is difficult to engage in the debate; no one has ever won an argument against a number). So: their cozy school is doomed. Shouldn’t policy makers take into account things like per pupil happiness?

Iowa is still 56,000 square miles, and still has 99 counties. Yet the abundance of school districts has gone the way of the Prairie Chicken. School districts have come to need more resources; accordingly they have tended to swallow up their neighbors or form marriages of convenience. In the 1985-86 school year there were 437 public school districts, over one thousand fewer than in 1960.

“The clock is wrong.” Street scene, Springville, Iowa. 6:46 PM. All photos courtesy of John Lawrence Hanson.

Since the 1980s the public school enrollment has been flat, but the number of districts has shrunk. The new millennium welcomed 374 school districts; fifteen years later there were 338. I understand that school districts might need to get bigger to survive, but the needs of our children haven’t changed. How does a community respond to the needs of its most precious members when the community itself has become a byzantine jumble of letters, featureless characters spread across the prairie? Where are AR-WE-VA, STARMONT, and BCLUW? The road maps are silent on this subject. Ask Siri.

“After Target Practice.” Kirkenes, Norway. Destroyed by Russian bombs during WWII, it’s a pragmatic Post-War rebuild.

In north-central Norway I had conversations with people who were alarmed by similar trends. The battles, in this case, were two. First, there was a change in airport priorities, with one town getting the upgrade and another town having its airport closed. Additionally, medical facilities were facing policies which employed back-biting economic strangulation to force a change. Medical specialties were purposely divided among three communities instead of being housed in an “efficient” single location. The small towns rightly understood that hosting a medical specialty was a statement about their right to exist in a world where efficiency was a new god.

Mount Pleasant, in Iowa, has similarly been a victim of this obsession with efficiency. More than the town’s Old Threshers Reunion, held each year in late summer, or Iowa Wesleyan University, which is based there, the Iowa Mental Health Institute had long been the consistent economic and symbolic pillar of the community. It substantiated Mount Pleasant’s right to exist, its claim on a future. No longer.

In the spring, I got to experience the Arctic outpost of Vardø—please take a moment to find it on map. Vardø is hard to get to, but it has a remarkably long and important history in a nation full of towns with long and important histories. In some ways Vardø reminded me of so many towns in the Midwest and Great Lake States. Maybe you have heard the slur, “Rustbelt?”

Vardø stands on the edge of Norway, and on the edge of western civilization. Outposts like this naturally hold perilous positions. In Vardø the weather is merciless, the Russians are next door, and the ups and downs of the fishing industry have left the town a shell of its glory days. Think of Fort Dodge, Iowa in 1979, compared to its reduced state today.

Vardø has to weather literal and figurative storms. Like so many other small communities in Norway, or in Iowa for that matter, Vardø resists. They resist having more of their administrative duties and positions reallocated to central locations. They resist going quietly. In Vardø, after all, the Norwegian flag flew longer in defiance of the Germans than anywhere else in occupied Norway.

“Subtraction by Addition.” Alburnett Middle/High School, Alburnett, Iowa. The historic building is on the left. Subsequent additions do not compliment the original.

The People of Vardø also resist through art. There, the handiwork of God and man is evident, with the latter being more sublime than the former. The town’s art is compelling and surprising, though. It resists through declarative street art, most of it sanctioned, some of it guerrilla, and none of it kitsch.

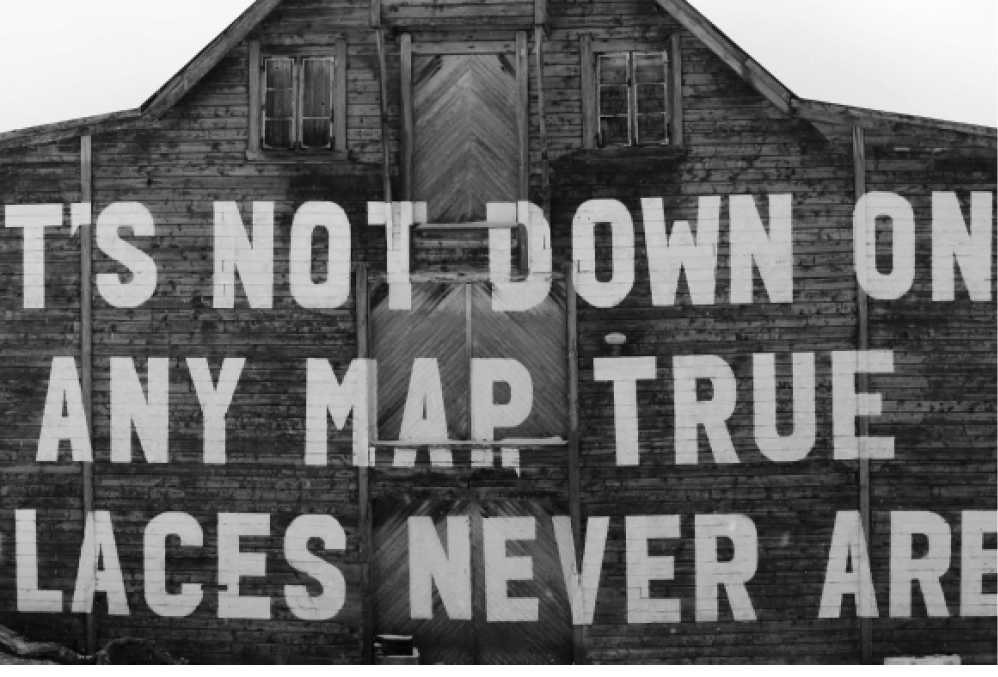

The street art necessitates serendipitous viewings. To walk with no plan in mind other than to be confronted with work that is familiar but strange at the same time. A colorful and cartoonish scene of sailors on leave wraps a building on the main street, while down another street, English words cover a warehouse. Across the harbor an oversized exhortation hugs a factory. On viewing it, I assumed it was pedestrian until a double take revealed it was indulging in blasphemy. Or was it playfulness? I guess I was supposed to wonder.

On another corner I was confronted by a giant bearded face. I wondered: did I know that face? Had I heard that phrase before? How come it was written in English? Those were typical questions that came to my mind, and as I mulled them I wondered how people resisted similar pressures back in my prairie home.

The small communities of Iowa and Norway are homes—to people, of course, but also to potential. Our plethora of small towns has infrastructure, utilities, housing…present but underutilized. We spend tax dollars to subsidize the building up of infrastructure in larger cities where it seems like they don’t need it, while we wring our hands, saying that our small towns are dying.

In a democracy, you get a vote and a voice in the process. But even in peerless democracies like Norway, there are many who feel like they are being ignored or worse, exploited. There are options: vote, lobby, organize…or fight. After her arrest for attempting to vote, Susan B. Anthony testified that she would not pay the fine, and instead would fight. She used a Quaker maxim to characterize her defense saying: “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

“You are here.” Abandoned warehouse with street art, Vardø, Norway.