American culture tends to disparage nostalgia. To hold a pronounced affection for things and ways of the past is seen as simple-minded at best, reactionary at worst, and frankly rather un-American. This nation has always seen itself as the land of the forward-looking, a nation of promising frontiers and fresh beginnings, grand opportunities, inventive entrepreneurs and new machinery. To participate fully in the mainstream flow of American life today, one must live always on the cusp of tomorrow.

I want to make a case for the legitimacy and value of the basic human response of love and longing that we call nostalgia, a state of “homesickness” that arises when things familiar and beloved are lost. In making this case I will describe the pronounced change-induced distress experienced by many Americans in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, and the modest but noteworthy contributions made in that era by one singularly nostalgic Midwestern gentleman, Ralph Lorenzo Warner.

From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, the United States underwent a profound, technology-driven transformation: the nation changed from largely agricultural to highly industrial, and from a decentralized, production economy to a centralized, consumption economy. The rise of an extensive transcontinental railroad network was central to these changes. Industrial cities boomed, with millions leaving their rural and small-town homes to work in urban factories alongside newly arrived immigrants. Electricity enabled many life-changing technologies, such as the telephone, incandescent lighting, and refrigeration. And there was large-scale tapping of petroleum coupled with the invention of the internal combustion engine and the mass production of the automobile—nothing else has changed the U.S. and the American way of life so greatly and rapidly.

The advent of this urban, industrial, polyethnic, railroad- and then automobile-oriented nation elicited a compelling range of responses among Americans who were reluctant, even unwilling, to let go of the country’s earlier ways of life. I have been interested for some time in these responses and have been drawn to explore the life and sensibilities of one particular individual, Ralph Lorenzo Warner (1875-1941). Warner’s response to the disconcerting agitation and upheaval of American life during his first several decades led him, in his mid-thirties, to create a little “land of long ago,” as he sometimes called it, in which to live and provide a respite for others.

I first ventured into Warner’s story when I was doing research for my book, A Passion to Preserve: Gay Men as Keepers of Culture. Warner created his little land of long ago in the unincorporated village of Cooksville, near Madison, Wisconsin. His house remains a private residence while many of his home furnishings and personal memorabilia have become part of the Cooksville Archives and Collections. I became fascinated with Warner as a pioneer in historic preservation, and as the first in a several-generation lineage of preservation-minded gay men who made their homes in Cooksville in the twentieth century.

Warner manifested an extraordinarily rich, quintessential mix of the five traits I came to identify as characteristic of preservation-minded gay men. These include gender nonconformity: being male with a significant feminine streak; domophilia: exceptional love of houses and things homey, a deep domesticity; romanticism: relating with extraordinary imagination and emotion to things and people of the past; aestheticism: artistic eye and aptitude, design-mindedness; and connection- and continuity-mindedness: valuing a sense of personal relationship with the flow of history. 1

In 1911 Warner bought an 1840s house in Cooksville and proceeded to furnish and live in it in a manner as consistent with the 1840s as he could manage: no indoor plumbing (water pump and outhouse in the backyard), no electricity (only candles and early oil lamps, kerosene being too modern), no central heating (fireplace only, stoves being too modern), and of course no telephone. His main concession to modernity was having a kitchen stove that burned kerosene rather than wood.

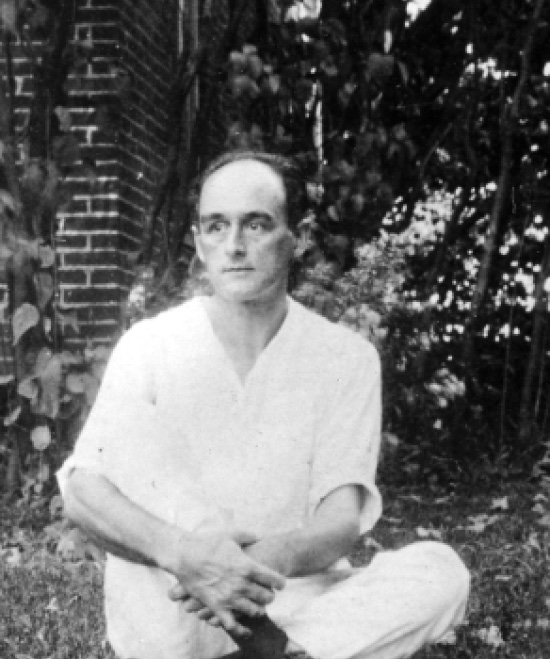

Ralph Lorenzo Warner, seated before the lilac bushes at the House Next Door. All photos circa 1920, courtesy of Larry Reed, from the Cooksville Archives and Collections

Warner called his place the House Next Door. Starting in 1912 and continuing until he suffered a disabling stroke in 1932, Warner hosted thousands of paying guests, one party at a time and by reservation only, from spring through fall. They came for luncheon or tea or dinner, to see the house and the antiques with which it was furnished, to tour the old-fashioned garden, to enjoy conversation with Warner and his piano artistry, and perhaps to join in singing. Old English ballads were a favorite—“Lord Lovel,” “My Man John,” and “The Raggle Taggle Gypsies, O!” Warner would sometimes dress in nineteenth-century frock coat, waistcoat, and top hat. Occasionally he provided bed and breakfast accommodations. Some guests visited numerous times. “It’s strange that the same people keep coming,” Warner told a reporter. “They bring others, of course, but they are always coming back themselves.” 2

Warner’s Cooksville home kept him very busy and the fees he collected from guests, supplemented by his piano students’ fees, constituted his modest livelihood. Although he depended on the income, he viewed the House Next Door not as a business but as a refuge from modern life. Feature articles in newspapers and magazines helped to publicize the place, which, in summer, was largely hidden behind a tangle of trees, bushes, and vines. Warner did no advertising and erected no signs to help people find the House Next Door. He preferred to have his guests learn of it personally, through word of mouth, and to experience it not as a restaurant or museum but as a gathering place for kindred spirits who felt out of step with the mainstream of modern life, and who found romance and beauty in the things and ways of the olden days.

Ralph Warner was ambivalent about engaging with the world in such an intimate way, having strangers come into his home. He was a creative homemaker, cook, and gardener, a gifted musician, bright, sociable, and talkative. But his heavily scarred facial complexion, the result of childhood smallpox, made him self-conscious, as did his rather feminine voice and manner. And as his flow of visitors grew through the years, his workload grew heavier. Ten years into operating the House Next Door, Warner asked a reporter not to write about him. “I already have too much to do,” he said. “I like company but not too many. I must be left alone. I have all this garden to care for.” 3

Newspaper and magazine writers described Warner as an artist, a musician, a pleasant, romantic gentleman. He was likened to Thoreau at Walden Pond, an exponent of simple living. A 1926 article in the Wisconsin State Journal described him as “a genial, cordial man, who enjoys people and guests more than anything in the world, with the exception, perhaps, of antiques.”

“Let me live in a house by the side of the road, and be a friend to man.” For most of us these lines represent a pretty sentiment, pleasant enough to repeat in idealistic hours, but out of the question for practice in this materialistic age. Yet occasionally we find a man, who, weary of the bustle and the petty bickerings of modern life, finds courage to retire to the side of the road and live his life in as idealistic a manner as his fancy may dictate. 4

Some writers hinted at Warner’s queerness, calling him a “delightfully temperamental antique collector” and a man whose tangled garden grew strange medicinal herbs that in earlier times would have assured his burning at the stake. 5 6 Near the end of Warner’s life, when he was no longer operating the House Next Door, a Milwaukee Journal reporter wrote, “He was a bachelor and he was different. …He always puttered around the house—cooking, making hooked rugs, collecting antiques and the like. Strolling around the village in his white pants, he always had plenty of time to talk when the farmers were busy with their chores. It was never ‘hotter’n the hubs’ to him. He would mop his brow with a silk handkerchief delicately and say, ‘Death, it’s so wahm.’ 7

Warner seems to have been remarkably self-possessed for a man whose coming of age in a working-class family coincided with Oscar Wilde’s much-publicized trial and imprisonment. When one visitor to the House Next Door asked, “Where is Mrs. Ralph?” he gave an evasive reply that was no doubt well-rehearsed: “All the ladies nowadays belong in the tomorrows and next days. I’ve never found one that fitted into my land of long ago.” As the visitor continued her inquiry with a comment on the matrimony vine growing over the door, Warner was quickly out the door and into the garden, intent on shooing a blue jay away from the pool. 8 Not all who visited were so nosy. Some of them, enchanted by Warner’s creation, sent him poems they composed in the afterglow of their visits.

To understand what Ralph Warner’s Cooksville haven meant to him and to those visitors in the 1910s and 1920s for whom it had great appeal, we must consider it in relation to Warner’s life and the realities of those times. It is telling that Warner viewed a house and garden from the 1840s—just seventy to eighty years earlier—as his land of long ago. Writings about the House Next Door from the 1910s and 1920s give us some idea of how very far back in time the 1840s seemed to Warner and his contemporaries, how completely American life was felt to have changed during the intervening seven or eight decades. One writer described the House Next Door as being “like a page from…an historical novel…filled with romance and glamor of the long ago.” 9 Another said that “in the midst of a bustling twentieth century environment” the house was a reminder of “an almost forgotten past.” 10 Today, a house recreating the domestic life of seventy years ago—the 1940s—would not likely attract so much attention, serve as a restorative for those discomfited by modern life, or be likened to a romantic novel harkening back to an almost forgotten era.

Ralph Warner was harkening back to his grandparents’ early-marriage years in Dodge County, Wisconsin, a farming region about sixty miles northwest of Milwaukee. With most needed goods and services produced locally, they did not often have to venture far—occasionally to the larger market towns of Columbus and Watertown, ten to fifteen miles away. A trip to Milwaukee, the nearest large city, required a long day of travel by horse-drawn carriage each way. It was a pattern of human settlement, movement, and commerce that had shaped their ancestors’ lives for centuries, with relatively small and gradual changes through time. Then the railroads came, revolutionizing land transport and thus transforming the human senses of time, distance, and place.

By the time Warner’s parents, James Warner and Alice Woodward, married in 1871, the railroads’ reshaping of life was well underway in the Midwest and throughout the nation. James Warner and his brother moved to Milwaukee for jobs with the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul Railway, whose line ran through their home township in Dodge County. Both resided a few blocks from the railway’s depot in the Milwaukee’s Walker’s Point neighborhood. Ralph Warner was born there in 1875 and was joined by two sisters through the next ten years.

Ralph Warner, in nineteenth-century attire, awaits visitors at the House Next Door

The family lived in Milwaukee for Warner’s first eighteen years, mostly in the neighborhood of his birth. During this period the city’s population grew from about 100,000 to about 250,000, reflecting not only the nation’s shift from agricultural to industrial but also the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Poland, Italy, and other European countries. Living in the railroad district, his father a locomotive engineer, young Warner would have been familiar with the growing size and diversity of the city’s populace.

Ralph Warner’s childhood visits to the home of his maternal grandparents, Stephen and Eveline Stewart Woodward, in their Dodge County farming community exposed the city boy to the quieter, cleaner, greener, more old-fashioned place his parents had come from—and to which he may have already had some longing to return. But along with the noise, pollution, and congestion of his Milwaukee neighborhood, the city offered Warner key advantages: good public schools and excellent musical instruction. He began taking piano lessons at age seven and demonstrated great talent. After going on to study at Chicago Musical College in 1896 and 1897 he returned to live with his parents, who had moved to the Racine area. He taught piano students and was noted for his fine piano performances in the community.

By 1900 Warner had taken a position as piano instructor at Morningside College in Sioux City, the Iowa move being his first significant departure from his parents’ home. Warner taught at Morningside until at least 1904 and was active in the city’s Beethoven Club. A local newspaper praised his “delicate yet strong touch and intelligent interpretation.” Other reviewers observed that “Mr. Warner unites delicacy with fire and vim by his technique,” that he imparts “an air of vagueness and mystery to all of his selections,” and that “his playing is marked with brilliant technique and poetic style, which gives excellent promise for his future.” 11

After several years as one of Sioux City’s finest pianists, Warner moved back to Wisconsin. During his years away the last of his grandparents had died—his mother’s parents, whose Dodge County home had been a feature of his childhood. After about ten years in the Racine area, his parents moved to Delavan, a small Wisconsin city about fifty miles west of Racine. Warner lived with his parents in Delavan and then in Walworth, a smaller city nearby. After living for many years amidst the unquiet of industrial cities, it was in tranquil little Walworth that Warner’s mother died in 1908, when she was 58. His father soon left for Florida, where he would reside until his death.

Alice Warner’s death seems to have been an important turning point for her son, then 32. Warner soon moved back to Racine, where he took a position as an instructor in arts and crafts, weaving in particular, at the North Side Boys’ Club, a charitable center for disadvantaged children and youth. In early 1909 he suffered a serious “attack of blood poisoning.” In the fall of that year he left Wisconsin for Forest Grove, Oregon, an 1840s-settled college town near Portland where, the Racine newspaper reported, “he will make his future home.” This venture to the West did not last long. In the fall of 1910 a Racine news article about the North Side Boys’ Club mentioned that Ralph Warner “will continue to have charge of the arts and crafts work classes.” 12

As industrial cities like Milwaukee and Racine were places of opportunity, they were also sites of unhealthy living conditions for many. Noise, overcrowding, air pollution, poor sanitation, and infectious diseases took a great toll. By the first decade of the 1900s, urban campaigns for public health had developed into integrated, citywide programs in many places, including Racine. In 1910 the North Side Boys’ Club joined with several other Racine social welfare organizations—Associated Charities, the Day Nursery, and the Big Sister movement—to form the Central Association, which received financial support from individuals and employers. In this era before government played any significant role in the social welfare arena, Racine’s Central Association was a progressive enterprise that was well supported by the community.

Living and working in Racine enabled Ralph Warner to meet others with similar interests and sensibilities who appreciated him as the rare bird he was. One such person was Susan M. Porter, sixteen years his senior and a history teacher at Racine High School. She had grown up in Cooksville and her affection for the place led her to purchase, in 1910, one of the village’s old brick houses facing the public square. Warner was just one of numerous Racine residents that Susan Porter introduced to Cooksville, but Warner’s visit in the spring of 1911 had special significance for both him and the village. Enchanted by the place, he learned that the brick house just south of Miss Porter’s was for sale, for five hundred dollars, and decided to make it his own. The seemingly whimsical name he gave it, the House Next Door, was actually born of his strong connection- and continuity-mindedness. His house’s name represented an important strand in his bond of friendship with Miss Porter.

The “go-ahead fellow” was a much-admired type in nineteenth-century popular culture, the sort of fellow many young men aspired to be: optimistic, ambitious, and energetic in pursuit of success and wealth in the business arena. Ralph Warner was not, by any stretch, a go-ahead fellow and he knew it. Several poems he saved from newspapers and magazines as a young man illustrate this awareness: “If I take the path to song and you take the road to gold, I wonder if we shall meet when the years are old?” 13 A newspaper-clipped poem sent to him by his cousin Ella observes: “He’s getting past the flush of youth, at times we think he’s lacking steam—some people say, to tell the truth, he’s less disposed to do than dream.” 14

Warner was a dreamer, but that did not mean he was indisposed to doing. However, the focuses of his doing were not of the American go-ahead variety. They had to do with things domestic, musical, artistic, and historical. And they were of the ministerial sort—attending to the needs of others, as in his secular ministry at the boys’ club in Racine. “Our greatest happiness in life consists in giving ourselves to the service of others.” This maxim must have had great resonance for Warner, considering that it is the only quote he copied into his poetry scrapbook twice. For several years in Racine his desire to serve others also earned him a modest living as a teacher and friend of needy boys. And then he discovered a new way in which he could serve, one that would enable him to escape the industrial city: creating his little land of long ago, where he would find his own fulfillment while ministering to those scattered souls who were similarly dismayed by the character of modern life and who shared his love for the things and ways of the olden days.

Historic preservation in the U.S. was in its infancy in the early 1900s, and was limited largely to the Northeast, where the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities was founded in 1910. (The ministerial inclination was at play there as well, with many ministers, former ministers, and seminarians among the group’s founding members.) For the recently settled Midwest, the House Next Door was an eccentric creation and a pioneering endeavor in the preservation arena. Ironically, it was the automobile that put Cooksville within reach of both Warner and his visitors, even as it was the automobile that was driving so much of the change that riled preservation-minded Americans. Warner didn’t ever operate a car, but his friends and acquaintances included numerous automobilists.

In furnishing his apartment rooms in the decade before he found his 1840s house in Cooksville, Ralph Warner combined an eclectic mix of furniture and decorative objects that were interesting, attractive, “old-fashioned things”—as what we now call antiques were then commonly called. Warner favored the spare, sturdy Arts and Crafts aesthetic and was well acquainted with Elbert Hubbard, the Roycroft community, and the periodicals, books, furniture, metalwork, and leather goods they produced in East Aurora, New York. And his work teaching weaving and other manual arts to boys in Racine was very much in line with the Arts and Crafts ethos.

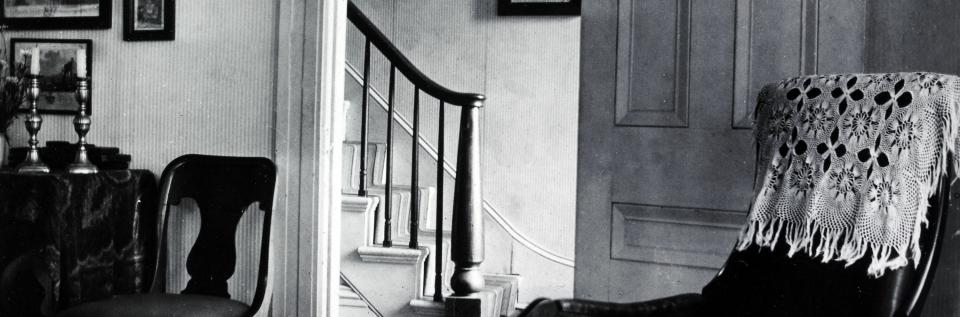

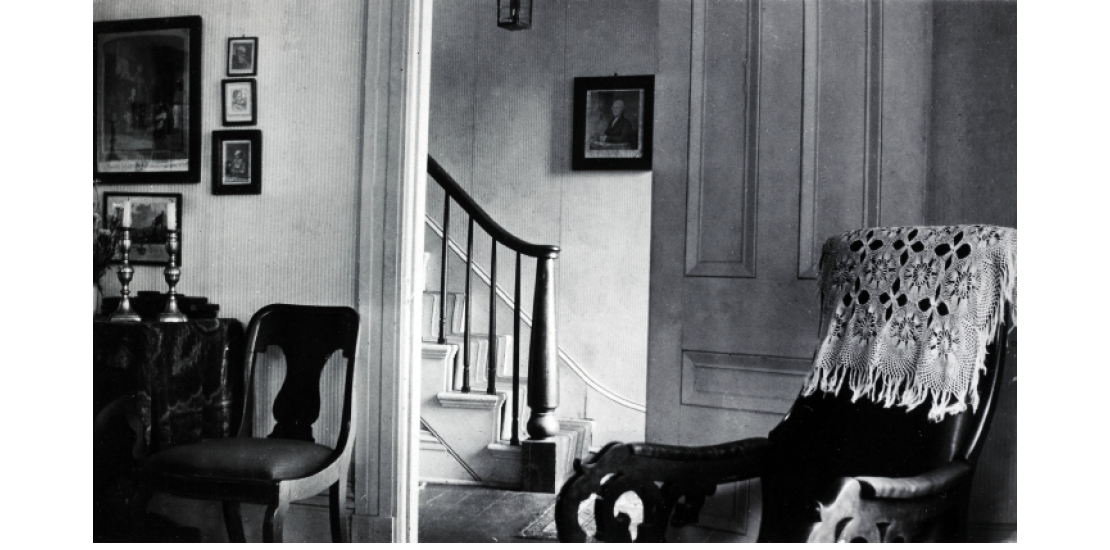

Inside the House Next Door: the view from the parlor to the front hallway

For his scrapbook Warner clipped inspiring bits of text from Roycrofters periodicals and copied by hand choice sayings from books they published. In Elbert Hubbard’s Little Journeys to the Homes of Eminent Artists Warner read about the sixteenth-century Italian Renaissance painter Antonio Allegri da Correggio. Hubbard described Allegri as an artist who “had come up out of a family that had little and expected nothing” and who, when traveling, “stopped with peasants along the way and made merry with the children, and outlined a chubby cherub on the cottage wall, to the delight of everybody.” 15

Warner would have had affinity with Allegri’s humble background and his way with children, but it was the final sentences of this paragraph that Warner copied into his scrapbook: “Smiles and good-cheer, a little music and the ability to do things, when accompanied by a becoming modesty, are current coin the round world over. Tired earth is quite willing to pay for being amused.” Warner would apply this formula quite effectively in his role as creator and proprietor of a refuge from modern American life.

Elbert Hubbard’s use of the phrase “tired earth” in the first decade of the 1900s is a reminder of the immense and exhausting ways in which American life changed through the first decades of Warner’s life. Walt Whitman remarked on this shift: “Singleness and normal simplicity and separation, amid this more and more complex, more and more artificialized state of society—how pensively we yearn for them! How we would welcome their return!”16 But most observers writing in this period—including even Whitman in some of his poetry—celebrated American industry and invention, describing with particular reverence big machinery made in the United States.

The widespread acclaim with which this technological progress was met in American culture is evident in “Dawn of the Century,” a popular piece of sheet music published in 1900. Prefatory words set the tone for the piece, characterizing the new century as a man-child born sturdy, strong, and beautiful, and bearing a shining scroll with predictions of peace and justice, love and truth, the end of wars and enmity—God’s fatherhood, the brotherhood of man.

The artwork on the cover of “Dawn of the Century” depicts the promise of the twentieth century, which is all about technology. A woman in flowing gown, crowned by an electric light bulb, stands on a winged wheel of Progress. Arrayed around her in the heavenly red-gold horizon of dawn are the promising machines: typewriter, telegraph, electric streetcar, dynamo, gasoline engine, telephone, sewing machine, camera, mechanical reaper, railroad locomotive, automobile.17

This ethereal image does not depict the nervous distress wrought by technology-induced change, especially among those living in America’s rapidly growing cities. As the rhythms of daily life were accelerated, there was an intensified pressure to be “on time,” the phrase a colloquialism born with the rise of factories and railroads. A widespread nervous syndrome, known popularly as neurasthenia, was said to be the result of “overwork, crowdedness, ennui, and other tensions associated with metropolitan living.” The New York Health Commissioner stated in 1895 that “in no nation at any time have the demands on the nervous forces been as great as in these United States.”

The House Next Door’s Parlor in winter

Neurasthenia changed the course of Wallace Nutting’s life. Born in 1861, Nutting was an early member of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. He had been a Congregational minister, but after recovering from neurasthenia he found a new ministry: creating a commercial enterprise centered on the Old America theme. The Wallace Nutting company sold millions of hand-colored photographs, signed Wallace Nutting, of evocative scenes of the olden days—colonial house interiors and exteriors, bucolic settings, some featuring models in period attire. With the huge nationwide popularity of these pictures, Nutting expanded his brand to include colonial furniture reproductions. He also developed a chain of restored colonial New England “house museums” as showrooms for his lines of pictures and furniture.

Warner was a regular reader of such magazines as Ladies’ Home Journal, House and Garden, and Country Life in America, so he would have become familiar with Wallace Nutting’s enterprises. Nutting’s pictures probably informed Warner’s interest in creating photographs of himself and women dressed in attire of the early nineteenth century. One of Warner’s photos is especially reminiscent of Nutting’s pictures: a shadowy view of his parlor, the backs of old chairs silhouetted against the snowy glare of windows, the floor dressed with hooked and woven rugs. Below the image he penciled Winter—House Next Door and signed it Ralph Warner.

Escaping to the countryside from the rapid pace of noisy, crowded, polluted industrial cities was a significant alternative-lifestyle impulse in the first decades of the 1900s. In 1909 Gustav Stickley observed, “Psychologists talk learnedly of ‘Americanitis’ as being almost a national malady, so widespread is our restlessness and feverish activity, but it is safe to predict that, with the growing taste for wholesome country life, it will not be more than a generation or two before our far-famed nervous tension is referred to with wonder as an evidence of past ignorance concerning the most important things of life.” 19

An influential proponent of this simple-living ideal, Ray Stannard Baker (1870-1946) was a confessed go-ahead fellow who made a decided change of course. Baker grew up in Michigan and through his twenties and early thirties pursued a career in reform-minded journalism, reporting on labor unrest and other social issues. Having burned his candle at both ends, Baker was in his mid-thirties when his book, Adventures in Contentment was published in 1907 under his pen name, David Grayson.

I came here eight years ago as the renter of this farm, of which soon afterward I became the owner. The time before that I like to forget. The chief impression it left upon my memory, now happily growing indistinct, is of being hurried faster than I could well travel. From the moment, as a boy of seventeen, I first began to pay my own way, my days were ordered by an inscrutable power which drove me hourly to my task. I was rarely allowed to look up or down, but always forward, toward that vague Success which we Americans love to glorify.

My senses, my nerves, even my muscles were continually strained to the utmost of attainment. If I loitered or paused by the wayside, as it seems natural for me to do, I soon heard the sharp crack of the lash. For many years, and I can say it truthfully, I never rested. I never thought nor reflected. I had no pleasure, even though I pursued it fiercely during the brief respite of vacations. Through many feverish years I did not work: I merely produced.

The only real thing I did was to hurry as though every moment were my last, as though the world, which now seems so rich in everything, held only one prize which might be seized upon before I arrived. Since then I have tried to recall, like one who struggles to restore the visions of a fever, what it was that I ran to attain, or why I should have borne without rebellion such indignities to soul and body. That life seems now, of all illusions, the most distant and unreal. It is like the unguessed eternity before we are born: not of concern compared with that eternity upon which we are now embarked.

All these things happened in cities and among crowds. I like to forget them. They smack of that slavery of the spirit which is so much worse than any mere slavery of the body. 20

This is a vivid description of the Americanitis to which Stickley referred, and a resolute rejection of city-centered life in favor of a restorative rurality. Never mind that Baker’s beloved farm existed only in his imagination. The millions who read his Adventures in Contentment and the books that followed found solace and inspiration in his critique of mainstream American life and his philosophy of right living. Given the strongly conformist character of life in that era, a dissenting voice such as Baker’s—railing against America’s “slavery of the spirit”—was extraordinary.

The lash under which Ralph Warner spent his twenties and early thirties—pursuing musical studies and a career as a pianist, losing his grandparents and his mother, making an aborted move to the West, engaging in urban social work—had taken a different sort of toll than that suffered by the hard-driving Ray Stannard Baker. But Warner was an artist, not a journalist, and creating the House Next Door was as central to his response as writing about fictional farm life was to Baker’s. It was Warner’s simple-living retreat from the hazards and hard edges of life in an industrial city, his quiet but eloquent rejection of the American go-ahead-and-don’t-look-back mentality. It was his aesthetically pleasing land of long ago, enabling him to create a home and engage in daily village life in ways that linked him to his grandparents and their rural lives in the early to middle 1800s, back before everything changed.

Much as Baker’s books were a reassuring revelation to frazzled Americans in the early twentieth century, so was Warner’s Cooksville home. For some visitors the House Next Door was notable mostly as a repository for the antiques with which it was furnished. For some, the house and its old-fashioned garden and the man who kept them were curiosities, the focus for an unusual automobile outing in the countryside. But for many who visited—whether in person or through feature articles in the pages of House and Garden, House Beautiful, Ladies’ Home Journal, and numerous Wisconsin publications—the House Next Door was valued as an inspiring respite from an unlovely American way of life.

Ralph Warner’s creation, born of nostalgia, was a gentle but insistent act of defiance. It was an artistic statement in celebration of things lost, and in opposition to many of the ways in which American life had changed and was continuing to change. Warner rescued and revived a house and garden which others had abandoned in their all-American pursuit of something better somewhere else. In lavishing his affection and creative artistry on the place, he created a haven not only for himself and his beloved flowers and birds, but also for many others who might have never imagined any alternative to the dictates of American consumer culture.

1 Will Fellows, A Passion to Preserve: Gay Men as Keepers of Culture (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 25-35.

2 Adelaide Evans Harris, “The Man in The House Next Door,” The House Beautiful, Jan. 1923.

3 Author unknown, “‘House Next Door,’ Secluded Home of Naturalist and Collector of Antiques, Draws Wide Attention,” Wisconsin State Journal, April 8, 1923.

4 Richard Brayton, “Antique Collector in ‘House Next Door’ Dislikes Modernism,” Wisconsin State Journal, August 8, 1926.

5 Author unknown, “Fascinating History Pulses through Dull Sheen of Dean’s Unique Pewter Collection,” Milwaukee Journal, July 21, 1946.

6 Eleanor Mercein, “Adventurous Cookery,” Ladies’ Home Journal, March 1933.

7 Author unknown, “Sleepy and Picturesque Cooksville Scorns Gasoline Pumps, Highways,” Milwaukee Journal, May 26, 1940.

8 May I. Bauchle, “The Land of Long Ago,” The Wisconsin Magazine, Sept. 1925.

9 Author unknown, “Picturesque Cooksville House Reproduces Days of Century Ago in Detail,” Beloit Daily News, June 10, 1921.

10 Ethel S. Raymond, “I Step into Paradise,” typescript, publication and date unknown.

11 Sioux City, Iowa, newspaper clippings, Nov. 25, 1902, Feb. 1904, and undated.

12 Racine Daily Journal, local news items, Feb. 17, 1909, Oct. 7, 1909, and Oct. 17, 1910.

13 Arthur Wallace Peach. “A Question.” Clipping, date and publication unknown.

14 Author unknown. “Some Day.” Clipping, date and publication unknown.

15 Elbert Hubbard, Little Journeys to the Homes of Eminent Artists, Vol. XI, No. 2 (East Aurora, NY: Roycrofters, Aug. 1902), 43-44.

16 David Shi, The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 156.

17 E. T. Paull, “Dawn of the Century” (New York: E. T. Paull Music Co, 1900).

18 Shi, The Simple Life, 176.

19 Gustav Stickley, Craftsman Homes (New York: Craftsman Publishing Co, 1909), 194-205.

20 David Grayson [Ray Stannard Baker], Adventures of David Grayson (Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co, 1925), 3-4.