I’ve always had a cat, both as a child and as an adult. I never cared much for dogs and was quite nervous around large breeds. So when my husband said he wanted to get a dog, my only requirement was that we get a puppy to ease the transition for me and my cat.

We did what many people do—we started looking at the pet ads in our local newspaper. We’d been hearing that goldendoodles were great dogs so when we saw an ad for goldendoodle puppies, we called and arranged to go see them. The kennel was located on a farm not far outside of town.

I remember getting out of our car and hearing a cacophony of barking, though there were no dogs in sight. The sounds were coming from behind a large building and a stretch of privacy fence. We were met in the driveway by a disheveled man who directed us into a makeshift office in the large building. The putrid smell of dog urine was terrible. We stood in the building and discussed our breed preference and when the man stated he had puppies available and began walking toward a door in the back of the room, we started to follow. But he turned, held up a hand to signal “stop” and told us he’d bring the puppies to us. While we waited, the stench of urine started to make me nauseous so I went back outside using the door we’d entered through. My husband and the man, his arms now laden with several pudgy puppies, soon joined me.

The man set the puppies on the ground. They were adorable, roly-poly bundles of fur, but that fur was filthy. They reeked of the same urine stench I couldn’t tolerate in the office. I couldn’t bring myself to touch them. My husband was more interested and coaxed them into play. One of the puppies took off romping behind the building and my husband chased after it. It was several months before he told me what he had seen back there.

That day we left the farm without a puppy. I couldn’t get past the smell and I felt guilty. But we kept checking the newspaper ads and eventually found our puppy; an eight-week-old corgi/rat terrier mix we named Ruby. I fell head-over-heels in love with this dog. So much so that when she was a few months old, I told my husband I wanted to get a second dog—a playmate for Ruby.

This time my search for a dog began on the Internet. I was still learning about dogs and never tired of reading about them; the different breeds, their temperaments, how to train them. At one point I came across a site with recommendations on how to find the “perfect” puppy. It included warnings about something called puppy mills, and said that one should avoid them. It included descriptions and photographs of conditions found in these puppy mills. I was saddened by it all. As I continued to read, it started to sound familiar–many dogs, filthy conditions, puppies offered without an opportunity to meet the mother. Was that first kennel we visited a puppy mill? I discussed my suspicions with my husband and he confirmed it. What he had seen when he chased the pudgy goldendoodle puppy that day was dogs in stacked cages, all of them jumping and barking frantically.

I was compelled to learn more, so I continued my online research and discovered that Iowa is home to hundreds of other puppy mills. Our little Ruby had become such an important part of my life, and the thought that others of her species were being subjected to some of the inhumane conditions I read about was not acceptable. I was confident that there must surely be an agency or organization working to effect change, so I went in search of them. Sadly, I was mistaken. I met with leaders in the area of animal welfare. Everyone I spoke to was familiar with the problem but no one knew of anyone doing much to address it. I could not walk away, and so started the path I’ve been on for the past seven years.

According to information on the website for the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, “puppy mills became more prevalent after World War II. In response to widespread crop failures in the Midwest, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) began promoting purebred puppies as a foolproof cash crop. Chicken coops and rabbit hutches were repurposed for dogs, and the retail pet industry—pet stores large and small—boomed with the increasing supply of puppies from the new mills.”

Today’s commercial dog-breeding kennels–those supplying puppies to the pet trade via brokers–are licensed and inspected by the USDA. These facilities are required to comply with the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA), which defines the minimally acceptable standards for animal treatment and care; standards such as minimum cage sizes, minimum veterinary care, acceptable methods of euthanasia, etc. The USDA employs inspectors who carry out unannounced inspections of thousands of licensed facilities all across the United States, including research facilities, animal transporters, exhibitors, and “animal dealers.” Dog breeders fall under the “animal dealers” category.

In 2008, Iowa was home to more than 450 USDA-licensed commercial dog-breeders. Accessing their inspection reports required that I submit a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. I submitted a request for “Iowa licensee data” and waited, having no idea what to expect in terms of what the data would look like or how much time it would take to receive. A few short weeks later I received an envelope containing several CDs. Each CD stored more than 1800 scanned pages of inspection reports and a variety of other documents. It was a dizzying amount of information. Each of the inspection reports included the name, address and USDA ID numbers, comments on the inspection results, and the inspector’s name. Flipping through the pages, most were single page documents with a simple notation, “No non-compliances noted.” But some were quite disturbing, with comments about sick and injured dogs, dogs living without protection from the elements, and dogs living in terrible filth and noxious environments. They were difficult to read and I vacillated between sadness and anger. But the vast majority of reports showed “No non-compliances,” so I started to think that this was an exercise in futility. Perhaps all the bad news I’d read online was inaccurate or exaggerated. I was hopeful—until a troubling trend became quite obvious; that the majority of inspection reports were signed by one particular inspector and that a suspicious number of this inspector’s reports included the notation, “No non-compliances noted.”

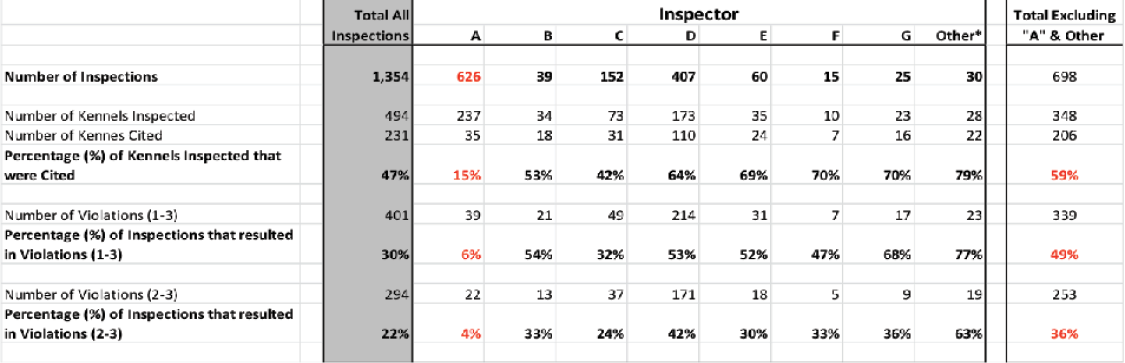

I commissioned a small database for entering and analyzing the data and spent hours inputting information from the inspection reports. I assigned values to the types of violations: “1” indicated a violation was related to paperwork or recordkeeping; “2” indicated a violation other than paperwork or recordkeeping and which were classified as Indirect by the USDA (not posing an immediate threat to the health or welfare of the animals); and “3” indicated Direct USDA violations (poses an immediate threat to the health or welfare of the animals). I also assigned an alphabet character to each of the inspectors. The inspector I was concerned about was assigned letter “A.” Here’s a table showing the results of my analysis:

My concerns were validated; inspector A’s inspection results clearly showed a problem. But I wasn’t sure what to do with this information. And I wasn’t sure who to turn to for direction.

At the same time, Tom Colvin, executive director of the Animal Rescue League of Iowa (ARL)—Iowa’s largest animal shelter based in Des Moines—was preparing for a second attempt to pass a law mandating better oversight of these commercial breeding facilities. Tom, with the help of a lobbyist, had been trying to amend IA Code Chapter 162, Iowa’s “Care of Animals in Commercial Establishments” statute, to allow for the inspection of USDA licensees by our state Department of Agriculture “upon receipt of a complaint.” Existing code included language which specifically excluded USDA commercial kennel licensees from any state-level oversight. Making this change to the law was no easy task. The dog breeders and various agriculture interests wailed at any attempt to pass better laws to protect animals. Iowa’s mammoth agriculture industry made sure these attempts didn’t succeed. And while Tom knew that there were significant animal welfare concerns within these kennels, he didn’t have hard data. Well, now we did. I shared the information with Tom and we discussed how it could buttress his efforts. He also shared a book with me, Get Political for Animals and Win the Laws They Need, by Julie Lewin—a publication of the National Institute for Advocacy for Animals (NIFAA). I finally had a roadmap for the grassroots effort Tom knew was necessary for success.

The Beginning of a Grass Roots Movement

As I’ve said, prior to this I had never cared much for dogs, and I had cared even less about politics. It seemed too big, too alien to my experience, so I avoided it. But Julie Lewin’s book explained the process so well, that I couldn’t put it down. I read it, made notes, attached Post-It notes and dog-eared several pages. (Have you ever noticed how often the word ‘dog’ is used in our language? Pay attention for a while. You’ll be amazed!) Of course mounting a campaign to achieve the necessary change was going to be a lot of work, but as I saw it, what other option was there? Now that I had concrete evidence of the severity of the problem, I couldn’t turn my back on these defenseless animals.

I decided to try and reach out to as many local animal shelters around the state as I could, to introduce myself and to share what I’d learned. But I didn’t have contact information for many of these shelters, and I didn’t want to simply drop in on them. I learned that an online pet adoption tool called Petfinder might be a good way of connecting with Iowa shelters. So I visited the site and indeed found that many, many Iowa rescue organizations and shelters were registered there, and most of them provided an email address. I spent more than a few hours one night copying and pasting all of these email addresses into my Hotmail account.

Now if you know anything about email providers, you know that Hotmail is not the most robust among them. But I honestly had no knowledge about my options, so I was resigned to using it. It only allowed for a finite number of addresses for any one email within a 24-hour period, and I planned to far exceed that limit, so I wasn’t going to get my email out as quickly as I’d hoped. I did what I could, and, one Friday night in the Fall of 2008, I sent several shelters and rescues an email detailing what I’d learned from USDA inspection reports, and asking for their help on the legislation. Because my email list exceeded Hotmail’s maximum, I had to send a second batch the following day and another the day after that to reach everyone. I went to bed that first night wondering what kind of response I’d receive.

The next morning I made a pot of coffee, poured a cup, and headed for my computer—anxious to see the response to the previous night’s email. Hotmail took especially long to open up. I wondered if I’d overloaded it somehow. It chugged and chugged and then suddenly, my inbox contents began to appear. My inbox was filled with replies! Emails from many of the addresses included information about mills that they’d known about for quite some time, but that they’d been unable to do anything about. Every email included a message of encouragement! And the same results occurred with the two additional batches of emails I sent out. I’d hit a nerve, and I knew there were people out there who would help get something done!

The job I held at the time required statewide travel, so I’d become quite familiar with the entire state of Iowa. Over the next several weeks I stopped in at many of the area shelters and rescues, both those which had answered my email and those which had not.

I learned that most of those running the shelters were already well aware of the extent of the problem, but felt powerless to change it. I determined that they were either too busy and/or short of resources to do much more than the bare minimum work required to house and care for the hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of homeless pets which ended up in their facilities each year. I had hoped the shelters would be my conduit to the community as I built a grassroots organization, but in most areas, it wasn’t to be. Two things held them back; 1) they were simply too busy taking care of animals to consider adding anything else to their workload, 2) they feared their nonprofit status would be threatened if they got involved with advocacy and I was unable to convince them otherwise. I would have to find another way.

Thank goodness for the Internet! And for PowerPoint! I set to work generating a powerful presentation and started booking library and other public meeting rooms all across the state. Then I began placing ads in the local newspapers, inviting all “animal welfare advocates” to learn about the puppy mill problem in Iowa and to learn what they could do to help. Finally, one wintry Friday afternoon, I set off for Davenport, Iowa to give my first public presentation at a rather run-down hotel. I had no idea how many, if any, attendees I would have. I set up my computer, connected to the rented projection system, and waited. A grand total of two people showed up. Perhaps I should have been disheartened, but I wasn’t. The two who showed up provided me with a wealth of information, and they offered up great ideas, so I was thrilled to have met them. I spent the night in Davenport with plans to drive to Cedar Rapids the next day for a noon presentation, and then on to Iowa City for an evening session. I woke up on Saturday to find the roads covered with ice. Just a side note—I’d had a terrible car accident on icy roads several years prior, so I wasn’t terribly comfortable driving on ice. But I was compelled to move on and drove behind a semi-trailer toward Iowa City on I-80, never getting above 35 mph. I got to Cedar Rapids finally. And thank goodness! The room was packed! And Iowa City was, too! I found the beginnings of what has become an amazingly active grassroots base!

I traveled to various parts of the state each weekend, giving between two and four presentations in as many different towns—collecting email addresses from attendees so I could follow up with them. But the going was slow.

The Iowa Legislature was convening and ARL had their bill ready to go. State Senator Matt McCoy and State Representative Jim Lykam agreed to carry the bills forward. To this day they continue to be the dogs’ staunchest allies in our Capitol.

In the course of my travels I’d collected approximately 500 email addresses of people who said they’d help lobby in support of the bill. When it was introduced, I was asked to rally the troops. But again, my awful Hotmail account limited me. Most of my messages had to be sent out in at least two batches. So my first Calls-to-Action were sent out with an initial batch going out in the evening, then I’d set my alarm and go to bed and wake up just after midnight to send the second batch out. This is how our first year of lobbying went.

Needless to say it was not optimal. But our grassroots followers were tenacious, and what we lacked in infrastructure, we made up for in enthusiasm! In fact, we had legislators asking us to stop the flood of emails into their inboxes. We respectfully declined, and reveled in the knowledge that they were hearing from us loud and clear.

I was asked to present to a House subcommittee to share the data I’d compiled. I wondered to myself: How the heck did I end up here? Before 2008 I hadn’t even known the difference between the House and the Senate, and now I was presenting to a subcommittee! I had to have my data down pat, so I spent hours checking and rechecking my results. I had pages and pages of inspection reports, but I wouldn’t have time to share many of those with the subcommittee. All I really had were numbers—important, but boring, numbers. Then, one glorious February day, I found in my mailbox an envelope with a couple of photos. The photos were really terrible and disturbing. They showed dogs in stacked cages in the back of a semitrailer. A short note accompanying the photos (one of them shown below) stated: “this place can be found at (address), Charles City, Iowa.”

Photo courtesy of Mary LaHay

The letter-writer told me that this “kennel” had existed for years and that there were at least three semi-trailers like this on the property. No heat, no running water, poor ventilation. But the breeder was USDA-licensed and inspected and, according to my data, had passed every inspection in the past three years. The inspector for this facility was our infamous Inspector A.

My heart ached for these animals and my head raged at the breeder. But now I had something more than just numbers. I could say, “See!”

I was nervous for the subcommittee meeting. Our Iowa state Capitol is an amazingly gorgeous building but it was also designed to be imposing, and it is. I sat in a huge room at a stately table across from three legislators and stated my case. Two of the three sat attentively and asked good questions. One sat and glared and occasionally scoffed at my comments.

The subcommittee voted to move the bill forward and the same happened in the Senate. At least three times a week for three to four months, I wrote emails to grassroots supporters with instructions on what they needed to convey. Still, the bill did not pass that year, and we geared up for the next.

But we were able to demonstrate to the USDA that they had a rogue inspector in their Inspector A, and he was no longer an inspector soon thereafter. If I never accomplished anything else, I would have considered this a success.

I continued to accumulate data and grassroots supporters throughout the summer and fall of 2009, and the bill was reintroduced into the 2010 legislature. We were a little better organized this time, and the bill passed after a lot of gnashing of teeth. Now we had a law which said that our Iowa Department of Agriculture could inspect a USDA licensee “upon receipt of a complaint.”

One of the ways that I celebrated this win was by adopting a dog that had been rescued from an Iowa puppy mill. I found my miniature poodle, Eddie, at Hearts United for Animals, a rescue organization in southeast Nebraska. They specialize in rehabilitating dogs that have been rescued from puppy mills like the one pictured in the image below:

Photo courtesy of Hearts United for Animals, Auburn, NE

This photograph shows the western Iowa facility where Eddie spent the first eight years of his life. I felt proud that my work just might help protect some dogs from suffering in places like this.

We started to see a dramatic drop in the number of USDA licensed dog breeders in Iowa. Within a year we saw the number drop from more than 450 to approximately 300. No doubt the removal of Inspector A had something to do with that, but so did the passage of some city ordinances around the country restricting the sale of puppies through pet stores. Our data showed that Iowa breeders were producing and exporting at least 100,000 puppies annually, so as the outlets dried up, likely so did the producers. But we still had at least 300 breeders and the USDA reports showed that up to 60 percent of them were being cited for violations to the AWA. The problem wasn’t fixed, and we couldn’t let up just yet.

We kept gathering data. Now the USDA was making inspection reports available online so we had better access. Several breeders continued to subject dogs to horrendous conditions, and we reported them to the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS) per the new law. Unfortunately, we didn’t see much improvement in the enforcement of our animal cruelty law. That’s what we’d expected to come from the new law—that IDALS would go into these places, see the problems, and then implement our state’s cruelty law as needed. That’s what it was for, right? Wrong. The sad truth, as we discovered, is that nobody wants to deal with this problem. We met with sheriff’s departments and county attorneys to discuss particularly problematic breeders, but our requests for help fell on deaf ears.

One of the more frequent, and understandable, reasons for not pursuing these cases… who pays for the care of the dogs if they have to be rescued? The law says that if the dogs are confiscated, a court has to hear the case within ten days to determine if there’s enough evidence to warrant confiscation. If the judge determines there is enough evidence, the dogs can either go to a rescue organization or be euthanized—whichever the county decides. But if the judge doesn’t find enough evidence, the dogs are returned to the original owner. Regardless of which way the decision goes, the county is responsible for the costs of seizing and holding the dogs until the decision is made. Have I mentioned the numbers of dogs we’re talking about? The USDA inspection reports also include a head count on the number of dogs on site at the time of inspection. Are you ready? For the year 2008, we found that 227 of the over 450 kennels in Iowa housed a combined 14,280 adult dogs. The majority of them kept fewer than 50 dogs, but 34 kennels kept more than 100 adult dogs. Five kept more than 200 and three kept more than 400 adult dogs! To this day, one Lee county breeder often has more than 1500 adult dogs. Who could possibly afford to rescue and house hundreds of dogs? Nobody. So they wouldn’t.

There are other states which are light years ahead of Iowa when it comes to animal welfare laws. Missouri has laws that provide simple, but extremely important improvements to standards: larger cage sizes, solid flooring, and access to the outdoors. Pennsylvania requires “unfettered access to an exercise area.” Virginia law protects consumers from fraudulent claims by breeders regarding the pedigree of dogs sold. Virginia, Oregon, Louisiana, and Washington place limits on the numbers of adult breeding dogs kept in any one facility. Ohio requires breeders to carry liability insurance. So we borrowed from some of these other states’ laws and found a couple of really common sense solutions: 1) require the breeders to carry a bond to cover the cost of a potential rescue, 2) establish a fund from a portion of the licensing fees for officials to tap into to cover rescue costs as needed. We opted to attempt to pursue an amendment to the existing dog breeder law which would require a bond. While preparing data to support that, I found another troubling pool of information. I learned that the USDA often takes photos of situations showing violations to the AWA. So I requested photos taken in all Iowa facilities during a particular time span. And I waited.

A few weeks later I received several CDs which held hundreds of photos. Reading about the problems was bad enough. Now I had to look at images of them. Here are just two of the photos, representative of Iowa mills, that we received:

Photos courtesy of Mary LaHay

I couldn’t help but think that the actual scene would be even worse with the addition of the sound of, in some cases, hundreds of dogs barking, compounded by the smell of their waste.

In fact, one inspection report for the facility in the photo above (dogs in semi-trailer) stated that the ammonia levels in the back of that trailer were so bad as to keep the inspector (NOT Inspector A) from being able to stay there long enough to adequately assess the dogs—the dogs that lived in that environment 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. And their sense of smell is much more acute than ours!

Our first and second attempt failed to gain an amendment which would provide for funding in the case of a rescue. So in 2014 we decided to go-for-broke and offer an amendment which would fundamentally change the law that applied to this industry. We reviewed laws from several other states and cherry picked those parts that could be most helpful. The bill we composed called for mandated inspections of USDA licensees by IDALS; it increased the breeder licensing fees to cover the costs of the inspections; it required IDALS to report all instances of violations to the Iowa cruelty statute to local law enforcement; and it provided for some bare minimum changes to humane standards, such as allowing the dogs access to the outdoors. Such a radical notion!

We knew getting the bill passed would be tough. Agribusiness had been our toughest opponent thus far, but we’d been meeting with various industry leaders to educate them on the issue and to calm their fears about the “slippery slope.” The breeders’ lobbyists (they have two!) were telling the legislators that we had ulterior motives—implying, that once we were done with dogs, we’d move on to hogs. Good grief. The fear-mongering that goes on when it comes to dealing with some factions of our citizenry is appalling! We’re working to help dogs. We’re a rag-tag bunch of citizens—most of us middle aged women. What kind of threat are we to agriculture? Apparently substantial. Who knew!

The opposition we faced in the Capitol was pretty standard; the usual, tired slippery-slope arguments and the cries that our attempts were anti-business. But we were ready for all that. One new piece of data that emboldened us—the Iowa Department of Revenue did research and found that fewer than half of breeders possess state sales tax permits! How could any ethical legislator support such a shoddy business? But what happened next really threw us for a loop. Our new and fiercest opponent ever (because they’re so highly respected) reared its ugly head… the American Kennel Club (AKC).

How could this be? AKC’s tagline is “The Dogs’ Champion.” How could they NOT be in support of what we’re working on? Well, as they say, follow the money. Documents show that many dogs in puppy mills are AKC-registered. So that means that the puppies of those dogs are eligible for registration, too. And there are fees associated with registering a dog with AKC. Bingo! The money. More puppy mills = more AKC registrations = $$$. Period.

Of course AKC couldn’t tell its minions that this is the reason for their opposition, and it needed the help of its minions to lobby on its behalf, so the organization sent out messages far and wide telling “hobby breeders” that our ultimate goal was to stop all dog breeding in the state. Oh good grief! No way! Where the heck did that come from? But the AKC apparently has very devoted members who do not question any communication coming from AKC headquarters. So dozens of hobbyists—some of them Iowa residents, some of them not—started barraging the Iowa legislators with outlandish comments and claims. We had to scramble hard to respond to them all. In the process, we found that many of the hobbyists had no idea what was in the bill, nor what was in current law.

But we couldn’t fend them off. So Senator McCoy, who was managing the legislation, organized meetings with several hobbyists and significant changes were made to the bill to make it more palatable. A special hobby breeder status was created, with lower licensing fees and relaxed inspection requirements.

That revised bill was introduced in the 2015 legislature. It passed two senate committees but senate leadership wouldn’t carry it forward. According to some sources, agribusiness is still the biggest reason it isn’t moving.

So here we are. We’re down to approximately 200 USDA-licensed dog breeders in Iowa. At last count in 2015, 41 percent had been cited for violations to the AWA. And right now we have one breeder who is so threatening toward inspectors that they have to be accompanied by law enforcement when they visit his facility. You and I are paying for that! Another breeder was fined $19,000 in 2011 for his violations to the AWA. To date, he’s only paid $1,000 of that amount, and simply ignores all court orders to pay up. Both of these breeders are still breeding dogs, and selling the puppies.

So: we’ll be back in the Capitol in 2016. Because dogs are still suffering. Because some breeders continue to skirt authority. Because the puppy-buying public is still being scammed. Because Iowa can do better. And you can help. Visit our website, www.iafriends.org, to learn more. Join our grassroots efforts by clicking on the Take Action tab to register to receive our updates and Calls-to-Action. The dogs need you.