Traditional Lakota belief is that their ancestors emerged onto this earth through a cave in what is now the Black Hills of South Dakota. The descendants of these ancestors are the Titonwans, and they organized themselves into seven oyates, or nations: Oglala, Mniconjou, Sicangu, Oohenunpa, Itazipco, Sihasapa, and Hunkpapa. Today these seven Lakota oyates constitute six federally recognized tribes in the United States and one first nation in Canada.

After their emergence the Titonwans joined the Oceti Sakowin confederacy, which is commonly and incorrectly referred to as “Sioux,” as the seventh, and youngest, Council Fire. The four oldest of the six earlier Council Fires, also known as oyates, constitute the Dakota division; the fifth and sixth oldest oyates compose the Nakota division.

What follows describes the governing structures developed by the Lakota oyates and the roles and responsibilities of their socially-sanctioned offices, or positions. Though a discussion of the personal characteristics of individuals who filled these positions is outside the scope of this report, we do believe that the range of their “leadership qualities” would align closely with leaders through time and across the world. In other words, leaders exhibit a shared range of “leadership” traits, regardless of where or when they lived. Governing structures, on the other hand, were and are developed and modified by societies and therefore embody the social and cultural values of societies in time and place. After discussing Lakota governing offices and their functions, we will identify trends in these structures and their implications for those wanting to model modern organizations on traditional Lakota ones.

Traditional Lakota Governance

The basic social unit of Lakota society was a tiyospaye, or extended family. Though a tiyospaye was governed in some sense, the source of authority over its internal interactions was kinship. In this account we will not examine tiyospayes, but rather larger residential communities composed of members of multiple tiyospayes, where true Lakota governing systems are found.

The traditional governing systems of Lakota oyates took several forms depending on the unit and activities involved. Lakota governance was complex and situational. The basic residential community of Lakota society was an otonwahe, similar to a town. But whereas towns today are typically conceived of as stationary, in Lakota society otonwahes were mobile. Regardless of how often they moved or where they were located, each maintained an oceti, or council fire, to signal its independence. Otonwahes featured a certain system of governance when they were located in place, but other systems were temporarily implemented when they moved, convened or were established for specific communal purposes, such as buffalo hunts or ceremonies. Also, when the number of residents of an otonwahe reached a threshold, we believe an additional level or levels of governance were put in place.

When an otonwahe was situated at a site, it typically had four types of governing offices. At the highest level was an omniciye, or council of men. One member of the omniciye was the itancan, or leader, whom the omniciye chose. The itancan, in turn, delegated much of the day-to-day governing of the otonwahe to a circle of advisors, each called a wakiconza. The fourth governing office of a stationary otonwahe was also a group of men. These akicitas, or marshals, enforced compliance both with Lakota social mores and with the explicit policies of the other governing offices. Residential communities with enough residents to constitute an otonwahe would have had these four governing offices. The following paragraphs provide a fuller description of each of these four types of office.

OMNICIYE. The decision-making authority within an otonwahe was placed in the hands of a council of respected men. Not limited by a specified number, nor inclusive of all eligible members, this group of men, the omniciye, tended to consist of older and respected men residing in the otonwahe. Admittance to the omniciye was by consent of sitting councilmen. The omniciye convened regularly around the otonwahe’s oceti, in a central meeting lodge where it deliberated on matters of public interest, determined its relations with other otonwahes, ruled on disputes between the otonwahe’s residents, and decided where and when to move the otonwahe. One of its key decisions, which occurred infrequently, was to choose from among its members a leader of the otonwahe.

ITANCAN. The itancan occupied the catku, or position of honor, in the omniciye meeting lodge, and it was the invitation by his fellow members of the omniciye to sit there that signaled his promotion to this office. He was the leader of the omniciye, and therefore of the otonwahe. Once appointed, he generally held this office for life, although the omniciye reserved the power to depose him. The role was usually, but not always, assigned hereditarily, passing from father to son. A man whose accomplishments were sufficiently impressive, though, could win the endorsement of the omniciye and earn this position. The itancan was the executive of the otonwahe, working to realize the omniciye’s resolutions, appointing akicitas to enforce these decisions, and leading the otonwahe’s larger military campaigns.

WAKICONZA. Ideally, an otonwahe would have had four wakiconzas selected by the omniciye. Any man residing in the otonwahe, including members of the omniciye, could fill the role of wakiconza. During a wakiconza’s one-year term, however, any other governing roles he may have had were suspended. During the day-to-day governance of the otonwahe, the wakiconzas mediated disputes among the residents of the otonwahe as well as between the people and the leaders, represented the decisions of the omniciye, refereed games among the people, and provided advice to the itancan. They were considered hunka, or relative, to everyone residing in the otonwahe.

AKICITA. The akicitas in an otonwahe were a police force of sorts. Appointed individually or as members of an okolakiciye, or society, these public servants enforced otonwahe policies and social mores. Even the omniciye, the itancan, and the wakiconzas were not exempt from the judgment and sentences of the akicitas. Different groups of men would serve as akicitas over the course of a year and during more specific otonwahe functions. The lead akicita was the eyapaha, or crier in the otonwahe. He was charged with announcing policies, moves, summons before the governing bodies, general news, and also with maintaining the otonwahe’s oceti. While akicitas could be called into this compulsory service by governing officials for a variety of purposes, the charge of akicitas was consistent: to enforce the authority of their appointers.

The above descriptions provide an outline for the day-to-day governance of a civil, stationary, Lakota otonwahe. Different structures governed the otonwahe during special times. Two such instances were when an otonwahe was moving from one site to another and during the wanasapi, or communal buffalo chase.

Moving the Otonwahe

Throughout the year, for various reasons, otonwahes moved en masse. As a community, all of the residents, all together, moved their otonwahe. The decision to move an otonwahe was made deliberatively by the omniciye, but the move itself was conducted under the exclusive authority of the wakiconzas. They alone decided when the tipis should be taken down, how far to travel, when and where to rest during the day to separate the journey into four equal segments, and when and where to erect tipis again at the end of the day. They decided whether the existing akicitas would police the move, or to appoint new akicitas for this purpose. In addition to compelling compliance with the pace and direction of the move, these akicitas scouted for game to feed the otonwahe residents, and for enemies from which to protect the residents. When the move was completed, oversight of the otonwahe transferred from the wakiconzas back to the omniciye, and authority reverted from exclusive to consultative.

Hunting Buffalo Communally (Wanasapi) An otonwahe, either independently or in collaboration with one or more other otonwahes, conducted a wanasapi in order to efficiently and collectively obtain meat for its residents. In many instances, a wicasa wakan, or medicine man, performed rituals to discern a probable location of a herd of buffalo. Whether by this or some other process, once a herd was located, the omniciye decided when to hunt, how long to hunt, whether to invite neighboring otonwahes, and other logistical concerns. During the hunt, governing authority shifted from the omniciye to the wakiconzas, and changed from a consensual model to an exclusive model. The akicitas policed the hunters and enforced the wakiconzas’ decisions. After a successful hunt, any surplus meat was apportioned by the wakiconzas, who advised whether the hunt was complete or was to continue for more meat. Once sufficient meat had been accumulated, the authority of the wakiconzas ended, and the omniciye resumed its day-to-day consultative authority.

Moving the otonwahe and hunting buffalo communally were two civil functions of the otonwahe that required a significant change in the day-to-day governing system. During these operations, the margin for error was dramatically reduced. In the first case, all of the otonwahe residents were exposed and therefore vulnerable to outside forces. In the latter case, all of the residents were depending on the hunt for meat to cure and store for times of scarcity. In both cases, authority shifted from the omniciye to the wakiconzas, and it changed from consensual to exclusive. Thus, during these critical times we see a change in who had authority as well as a change in the nature of that authority.

Another governmental shift occurred when many otonwahes convened, typically in the summer, for any number of purposes, including tribal deliberations, appointment to tribal offices, and preparation for pubic ceremonies. Even though a resulting otonwahe tanka, similar to a city, coalesced for a relatively brief period of time, it nevertheless faced unique challenges, one of which was maintaining social unity among its residents—and by extension, their tiyospayes.

Integral components of Lakota social order that mitigated this potential disunity were okolakiciyes, or societies, that cross-cut social units as well as residential communities. Because their memberships were drawn from across different tiyospayes and otonwahes, okolakiciyes inherently promoted integration among the residents of an otonwahe tanka. It is not surprising, therefore, that okolakiciyes assumed decision-making authority at all levels of governance in an otonwahe tanka. The following paragraphs briefly describe three of these okolakiciyes.

NACA. The decision-making authority in otonwahe tankas rested with one of a select set of okolakiciyes, or societies. For purposes of this report, we call a member of any of these societies a “naca.” Whereas each of the men in a day-to-day omniciye may have been affiliated with a different okolakiciye, the nacas governing an otonwahe tanka all belonged to the same okolakiciye. The nacas convened regularly around the otonwahe tanka’s oceti in a central meeting lodge where it deliberated on matters of national interest. One of its key decisions was to appoint wicasa yatapikas.

WICASA YATAPIKA. The nacas chose four men for this special office. During large gatherings, these four wicasa yatapikas, or shirt-wearers, assumed a position of prestige. They tended to be younger and to have distinguished themselves in battle. They were guardians of the entire oyate, or nation, both literally and figuratively. As such, they were referred to as “praiseworthy men.” Their office was denoted by a shirt fringed with hair, which the people considered “owned by the tribe.” As was the case with an itancan, a wicasa yatapika held the title for life, although the nacas could depose him. Unlike an itancan, though, this office was not hereditary.

WICASA WAKAN. The role of wicasa wakan, or holy man, was conferred by the spirits. His authority was understood to come from direct communications with Wakan Tanka. He was relied upon for intelligence on the whereabouts of buffalo and to foretell the success of a war campaign, among many other things. Similar to a naca, a wicasa wakan belonged to one of a select set of okolakiciyes. During a Sun Dance the governing authority of the otonwahe tanka shifted from the nacas to the wicasa wakan. Then, at the end of the ceremony the authority of the wicasa wakan ended.

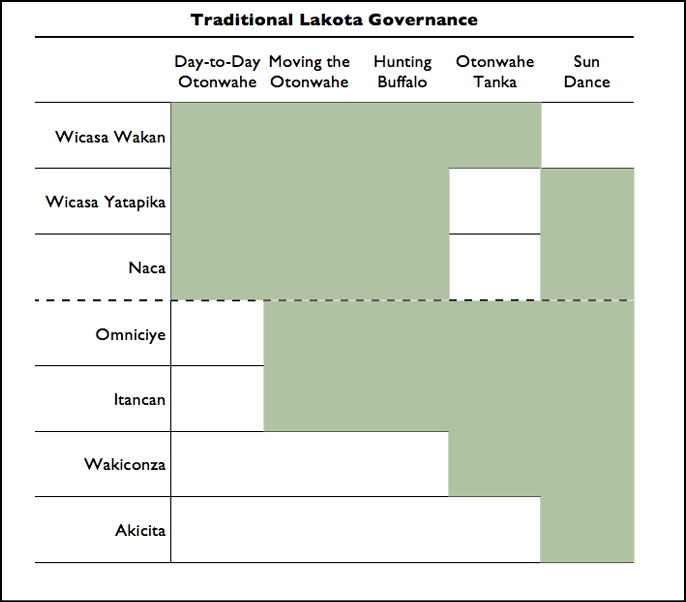

When the purpose was fulfilled for which an otonwahe tanka coalesced, then the otonwahe tanka devolved into a number of otonwahes. Under the authority of their wakiconzas, these otonwahes set off for distant places. Upon arrival there, the governing authority of each would shift from its wakiconzas to its omniciye. The different otonwahes would thereby resume their day-to-day organizational structures once again. The table below exhibits what offices govern the different situations we have examined. The empty cells indicate governing authority. Shaded cells do not indicate the absence of this office but rather the absence of its governing authority.

Shifts in traditional Lakota governance structures over time.

Principles of Lakota Governance

A critical characteristic of traditional Lakota governance is its complexity. From the information presented above we can abstract the following principles of Lakota governance.

There is a set of governing systems from which to choose. There is no fixed, unitary system of authority applicable throughout the course of a typical annual cycle. While all of the civil systems share the similarities of a council, its leader, and enforcers, the order and nature of their authority varies. Complementary systems of governance are substituted seamlessly in predictable ways to meet the needs of specific situations.

The day-to-day system relies on deliberation, consensus, and delegation. Decisions are resolved after careful consideration and discussion. It is very rare that the decision-making and the execution of decisions are done by the same office. It is similarly rare that the office carrying out a decision acts alone. Rather, it delegates to a small group of lead deputies or implementers, who in turn appoint their own enforcers to ensure the policy’s implementation.

At critical times, a system of exclusive authority emerges. When a situation has a narrow margin for error, all decision-making shifts to a small and select group whose authority is unimpeachable and whose decisions are unquestionable. Such times are finite in duration, and upon their conclusion decision-making reverts to a deliberative and consensual model.

During large gatherings, subgroups that cross lines of difference cohere the assembly. Participants in a large assembly are also members of subgroups according to their affinities and skills. These subgroups cross-cut normal organizations and contribute to the unity of the assembly. Some of these subgroups even play governing roles over the assembly, ensuring that the interests of all those gathered are put before the interests of any single constituent. Through all we have examined so far, a critical characteristic of traditional Lakota governance is its complexity. We will discuss the implications of these principles—and complexity above all—presently.

Implications for Organizations

The Lakota identity of a corporation is not determined by the membership of its board or staff, where the corporation is located, or whom the corporation serves. Modern corporations staffed by Lakotas, located within Lakota lands, and serving Lakota people are not necessarily “Lakota.” For example, a United States Post Office staffed by citizens of the Oglala Sioux Tribe (OST), located in the town of Pine Ridge, and serving residents of that town and the surrounding area, is not a Lakota organization. A school staffed by OST citizens, located in Pine Ridge Reservation, and serving citizens of the OST, is not necessarily a Lakota organization. Lakota-ness is more complicated than the demographic characteristics of staffs and constituencies, or the spatial location of facilities; in other words, it is more complex than biological background or spatial coordinates.

The following recommendations, then, may be applied to any organization seeking to develop an institutional identity that is Lakota. Our study is not normative, neither arguing for or against the efficacy of traditional Lakota governance, but rather descriptive. In other words, we are not advocating the adoption of these principals categorically. While they were written first for nonprofit corporations, they should be readily adaptable to any organizational structure. In the rich discussion of what it means to “be Lakota” that exists among Lakota communities and in entities that work with Lakota communities, the majority of the arguments revolve around language revitalization and land retention. This study of governance design is a different contribution to the discussion of Lakota identity.

Two strategies for implementing the principles discussed above into a nonprofit corporation are through its Articles of Incorporation and its Bylaws. The former includes basic information mandated by state or tribal statute. With regard to the State of South Dakota, this information includes the entity’s name, its period of existence, its purpose, whether or not it has members and how classes of these members are defined, the method of appointing directors, the provisions for regulating internal affairs, the number and names of its board of directors, and the names and addresses of its incorporators. Of these articles, those dealing with members, classes of members, the appointment of directors, and the regulation of internal affairs are the most readily adaptable to the principles of Lakota governance.

There are even more strategic possibilities in the corporation’s Bylaws. These documents are created by a corporation for governing itself and do not require specific criteria. Bylaws therefore are the best place for a corporation to more fully align itself with the principles of Lakota governance. As such, the corporation is like an otonwahe. This means that the entity is Lakota, rather than its members, the people with whom it interacts, or its location. People will come and go, and the corporation must remain Lakota regardless of who runs it.

Finally, the most fundamental principle of Lakota governance may be its complexity. There is no single manifestation of Lakota governance, and therefore no one “authentic” or “traditional” model of a Lakota corporation. Corporations that strive to identify themselves as Lakota will have to think critically and creatively about how to incorporate the principles of Lakota governance articulated above into their organizational documents, and thereby their day-to-day operations. And when they do, then they rightfully can call themselves a “Lakota corporation.”